![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Supply chains cannot tolerate even 24 hours of disruption. So if you lose your place in the supply chain because of wild behavior you could lose a lot. It would be like pouring cement down one of your oil wells.

—Thomas Friedman

The array of products readily available to consumers today is astonishing. Yet most of us take for granted the supply chains that make and deliver these products. When we shop for goods, whether online or in stores, we expect to find products available. Although occasionally we need to wait longer than we’d like or have to accept another product as a substitute, we usually find what we are looking for. But if we are honest with ourselves, we know that it is a minor miracle that the product—any product—is sitting on the shelf when we seek it. To get the right product to the right place at the right time requires that a lot of things go right over the product’s long journey from raw ingredients to final form. Opportunities for disruption arise at every step.

Supply chains fail in big and small ways. They can fail slowly over long periods because of systemic problems, such as those underlying the centralized planning economies of the Soviet Union and eastern bloc nations. Or they can fail suddenly and dramatically due to unexpected stresses, such as those caused by natural disasters. They also fail frequently in various smaller ways, as when products stock out in supermarkets because of demand spikes or when key industrial ingredients suddenly become scarce, such as drywall in the construction industry in 1999 or power transistors in the electronics industry in 2010.

While we may be aware of shortages or other supply chain problems that arise from time to time, the major challenges and inefficiencies of operating a supply chain are often hidden from view. But as anyone involved in supply chain operations knows, problems are plentiful. Malcolm Gladwell, in an article about the disposable diaper industry writes,

Out-of-stock rates are already a huge problem in the retail business. At any given time, only about ninety-two percent of the products that a store is supposed to be carrying are actually on the shelf—which, if you consider that the average supermarket has thirty-five thousand items, works out to twenty-eight hundred products that are simply not there. (For a highly efficient retailer like Wal-Mart, in-stock rates might be as high as ninety-nine percent; for a struggling firm, they might be in the low eighties.)1

You can argue about whether an out-of-stock situation in a retail setting causes greater harm to the retailer’s sales or to the vendor whose product has stocked out, but the harm to sales and profitability to both parties is nonetheless real and significant.

The flip side of out-of-stock problems is excess inventory. Companies invest a lot in inventory. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. domestic real manufacturing and trade inventories at the end of first quarter 2010 amounted to approximately $1.3 trillion on annualized sales of $11.5 trillion.2 This means that for every $9 in annual sales, approximately $1 is invested in inventory, of which roughly 25% is in raw materials and work in progress (WIP) and 75% is in finished goods. Most of this inventory, of course, is not excess, but companies in diverse industries routinely write off 3% to 5% of inventory each year as excess and obsolete, which translates to about $40 to $65 billion in inventory every year that is thrown out, destroyed, or otherwise disposed of.

Even when supply chains seem to be functioning more or less properly, this does not mean they are being run at the right level of efficiency and responsiveness. Efficiency is about cost effective use of assets; responsiveness is about providing the appropriate level of customer service, both in terms of speed of response and in the assortment of products that are available. Finding the right balance between efficiency and responsiveness is a perennial challenge and one that is central to effective supply chain management. An exclusive focus on efficiency leads to bizarre ends, as Jagjit Singh recognized when he wrote about an efficiency expert who visited a symphony concert at the Royal Festival Hall in London and reported the following:

For considerable periods the four oboe players had nothing to do. The number should be reduced and the work spread evenly over the whole of the concert, thus eliminating peaks of activity. . . . Much effort was absorbed in the playing of demi-semi-quavers; this seems to be an unnecessary refinement. It is recommended that all notes should be rounded to the nearest semi-quaver.3

By the same token, an excessive focus on responsiveness leads to equally bizarre results, as Marshall Fisher explains in discussing the toothpaste industry:

A few years ago, I was to give a presentation to a food industry group. I decided that a good way to demonstrate the dysfunctional level of variety that exists in many grocery categories would be to buy one of each type of toothpaste made by a particular manufacturer and present the collection to my audience. When I went to my local supermarket to buy my samples, I found that 28 varieties were available. A few months later, when I mentioned this discovery to a senior vice president of a competing manufacturer, he acknowledged that his company also had 28 types of toothpaste—one to match each of the rival’s offerings. Does the world need 28 kinds of toothpaste from each manufacturer?4

Undue attention to responsiveness can also be manifested in overly aggressive service-level targets. It’s not unusual for companies to promise the same high level of service for all products and all customers. For example, one large computer manufacturer targets shipment of all orders within 10 days of order receipt, regardless of the type of computer ordered, the complexity of the order, the lead time for the parts, or the type of customer. Such a one-size-fits-all approach not only is expensive but also usually fails because companies don’t make the necessary investment in inventory and resources to maintain such service levels across the board. Finding the right level of responsiveness requires making difficult choices about service-level differentiation: what level of service to provide to different customers and for different products. Adopting a uniform level of service across all products and customers may sound simple and egalitarian but almost never is the right choice.

Companies with inefficient or unresponsive supply chains can mask problems with extra inventory and through operational heroics, which amount to incurring extra costs to expedite orders that are in danger of being lost because of delays. Both of these fixes are expensive and the costs associated with them are often not easily visible, get built into the cost base over time, and are difficult to remove later. Nonetheless, they can be effective. As a result, companies often come to believe that these solutions—holding lots of inventory or having teams of expeditors—are a necessary cost of doing business. But often, they are necessary only because they are doing a poor job of supply chain planning.

About Supply Chain Planning and Analytics

To run a supply chain effectively requires smart supply chain planning. If your customers expect products to be available when they order them, you need to plan for adequate supply so that you can respond to orders as soon as they are placed. This is true regardless of the manufacturing or distribution philosophy that your company adopts: build-to-forecast, build-to-order, just-in-time, quick-response, mass-customization, sense-and-respond. All of these approaches require making decisions about what products to produce or procure before knowing what actual demand will result. For example, in the case of building products to order, you still need to anticipate and plan for enough supply in the form of parts and resources in order to effectively respond to orders when they arrive. The level at which planning needs to occur will change depending on the production model you follow, but supply chain planning remains a critical function in the operation of any supply chain.

In short, supply chain planning involves making decisions about what parts to procure and what products to produce before knowing what actual demand will result. These planning decisions are difficult because they must be made with uncertain and conflicting information about future demand, available production capacity, and sources of supply. In most companies, reaching these decisions is a highly complex balancing act, involving trade-offs along many dimensions (e.g., inventory targets versus customer service levels, older products versus newer ones, direct customers versus channel partners) and requiring the compromise of constituents—sales, marketing, operations, procurement, product development, finance, as well as suppliers and customers—with varied objectives and incentives. In short, the supply chain planning process is all about deciding the right level of responsiveness and efficiency to target and figuring out how to achieve these targets. The ability of a company to nimbly navigate this planning process without giving too much influence to any of the parties involved largely determines how well the company can respond to changing market conditions and ultimately whether the company will continue to thrive.

Uncertainty is at the heart of why supply chain planning is challenging and sometimes counterintuitive. A number of books have appeared in recent years that describe how easily human beings are fooled by randomness.5 We see patterns where none exists, and we are susceptible to a variety of statistical biases that distort our understanding of the world. These distortions affect our ability to plan reliably. If you know that you are going to sell exactly 100 widgets and your supply is 100% reliable, matching supply with demand is fairly straightforward. But if you don’t know the demand for widgets and your supply is unreliable or constrained, then the problem is not so simple. And yet this is exactly the situation many companies find themselves in.

Too often, supply chain planning is poorly defined and badly executed. Poor or ineffective supply chain planning processes can manifest themselves in a variety of ways. In many companies, operations personnel view themselves as the white knights whose role it is to meet the changing demands for products placed on them at any cost. This load-and-chase mentality may appeal to the can-do work ethic that many companies want to instill in their workers. But it is often symptomatic of a fundamental and unhealthy power imbalance between the sales organization and those responsible for product supply that leads frequently to inefficient and counterproductive decisions. For example, in one semiconductor manufacturing company, more than one-third of wafer lots in production at any given time are flagged as “hot,” a designation that gives them priority over other jobs. The fact that so many lots are hot, though, coupled with the fact that the designations change day by day means that little is achieved in terms of reduced cycle times or better on-time delivery.

In other situations, we find exactly the opposite mentality: plant managers who are constantly second-guessing what the sales personnel are forecasting or making on-the-fly decisions on their own about what to produce because of insufficient guidance from the sales, marketing, and finance organizations. This situation sometimes arises when supply chain planning occurs at too high a level to be of practical value to the plant manager, who must frequently make decisions not only about what product lines to produce but also about what the volumes will be for the products that compose each product line. If the output of the planning process dictates that 10,000 Rapid Cool air conditioners are to be produced, the decision leaves much to the imagination of the plant manager, who has to decide on the basis of too little information how to allocate production of these 10,000 units among the 30 different models composing the Rapid Cool brand.

Even when the planning process does produce a production plan at the granularity needed by operations, the decision process is often flawed, resulting in poor product mix decisions that do not incorporate profit margin and market opportunity differences among different products. This type of problem arises from confusion between management objectives and forecasts. In a typical company, at least two different estimates of future demand are generated, both referred to as forecasts. One forecast—sometimes called a revenue forecast—is generated by starting with revenue projections made at the highest levels of a company and working down from there to a set of projections at a product family level that, when aggregated, will meet the revenue projections for the company. More often than not, these revenue projections are not estimates of the most likely revenue that the company will achieve; rather, they represent targets, sometimes highly aggressive, that the company would like to achieve. Another forecast, often called an unbiased forecast, is generated based on historical sales patterns and often use statistical methods—sometimes sophisticated but more often simple—to project the most likely estimates for future demand. These forecasts are usually generated at the most detailed level for which adequate sales data are available, often at a much lower level of granularity than the level at which the revenue forecast is generated.

The key observation frequently missed by companies is that these two forecasts, even when specified at the same level of granularity, are not estimates of the same quantity: The revenue forecast embodies an estimate of what the company’s objectives are; the unbiased forecast reflects an estimate of the most likely demand to be realized. These two quantities are usually at odds, as they should be. Any participant in supply chain planning knows that the revenue forecast almost always exceeds the operations forecast. The discrepancy between these two forecasts is usually resolved by uniformly scaling the operations forecast upward so that, in aggregate, the operations forecast matches the revenue forecast. But in doing so, companies are missing a potentially enormous opportunity to improve profitability.

This book focuses on the three interlinked processes that compose supply chain planning: demand planning, sales and operations planning (S&OP), and inventory and supply planning. Some companies may refer to these planning activities by other names, but they all struggle with the ongoing effort of matching unknown future demand with sometimes variable and constrained supply. That is what these three processes are intended to accomplish. If executed well, these planning processes will help a company to achieve its targeted balance between efficiency and responsiveness. If executed poorly, they can be the root cause of any number of supply chain problems:

- Dissatisfied customers because products they order either are out of stock or arrive late

- Angry suppliers because purchase orders are constantly changing

- Excess procurement costs because of parts expediting

- Distribution headaches because expedited orders are blowing the logistics budget

- Production disruptions because parts are not available for half the production orders while the other half are being expedited

- Finance complaints because too much cash is tied up in working capital

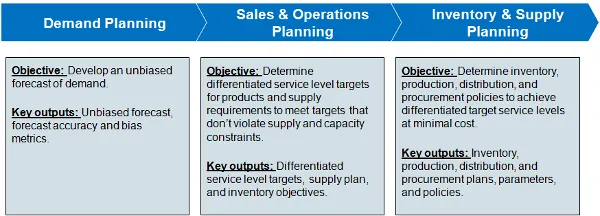

Figure 1.1 describes the logical flow of the three processes composing supply chain planning. The process starts with demand planning, the objective of which is to create an unbiased forecast of future demand. The unbiased forecast is then utilized by S&OP to decide the right level of supply to target for products. The objective of the S&OP process is to utilize the unbiased forecast together with information about demand variability, supply availability, resource constraints, and revenue objectives to derive a set of service-level objectives for the company, as well as cost estimates to attain these objectives. The success of the S&OP process should be judged by how well the company meets these service-level and cost objectives. The last step in the process is inventory and supply planning, which is concerned with how to implement inventory, production, procurement, and distribution policies to achieve the sales and operations plan. The goal of inventory and supply planning is to determine exactly when parts or products need to be manufactured, ordered, and delivered to meet service-level requirements and cost objectives set by the S&OP process.

The objectives and interrelationships of these processes may appear simple and logical enough, but companies rarely get them right. Sometimes the problems are organizational in nature—for example, a lack of clarity on what groups in an organization have responsibility for which planning activities or a lack of end-to-end accountability for the results of the planning process. More frequently, however, the problems companies face have to do with the practical and technical challenges of executing each planning process effectively—that is, ensuring that the steps and outputs of each process are well defined and that the right software tools needed to carry out the processes are in place.

It is these practical challenges of supply chain planning on which this book is focused. My approach to addressing these challenges tends to be analytical. Thus this book is just as much about supply chain analytics—how analyt...