![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE ORIGIN OF THE CAMPAIGN

The aftermath of the communist Tet Offensive in 1968 brought with it a change of resolve in Washington for a long-drawn war in Vietnam. Even if the local Viet Cong forces and its administrative infrastructure had been badly defeated, the US was mired in a strategic stalemate with North Vietnam as they had shown no sign of abandoning the objective of imposing communist rule in the South.

An increasing percentage of American public opinion now openly questioned the reason for fighting there – and in view of this in 1969 the United States initiated its ‘Vietnamization’ policy in South East Asia. The ever-increasing public sentiment further led the new Richard Nixon administration to call for a ‘highly forceful approach’ to the policy so that South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu assumed greater responsibility for the war-effort. The devised scheme called for a massive upgrade of South Vietnamese military capacity whilst gradually reducing the number of US troops deployed in the field. Four years into this policy, significant results were witnessed in South Vietnam, with 47,000 guerrillas that had ralllied the government in 1969, and 32,000 in 1970, a trend that continued the following year. Even if one is cautious using Vietnam War statistics due to different collation methods, by early 1972 guerrilla activity in the countryside was at its lowest ebb for decades. The Viet Cong had also not been able to recover from the losses suffered during the Tet Offensive and the heavy fighting of 1969–1970. Its underground administrative network had also been badly weakened by Operation Phoenix coordinated by the CIA, where between 26,000–41,000 suspected enemy civilians were ruthlessly executed. The rural economy was now also recovering thanks to massive US economic aid and an agrarian reform program initiated by Saigon. US advisors attached to the pacification campaign repeatedly indicated that the situation was steadily improving, with most of the South Vietnamese peasants rejecting the Viet Cong and people showing no real enthusiasm for the corrupt regime.

Tactically the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) brought in over one million men, including half of them from peasant militias to support most of the combat operations. The newly reinforced units were at the vanguard of the cross-border operations into Cambodia in 1970 and in Laos in 1971, in order to destroy and disrupt the enemy logistical system. These operations revealed the strong and weak points of the ARVN (for example, when it operated a common US-South Vietnamese offensive benefiting from American expertise, like in Cambodia). They performed well – running aggressive sweeps. In Laos they had no American advisors due to political rumblings and thus engaged in insufficient numbers which meant the ARVN were less effective.

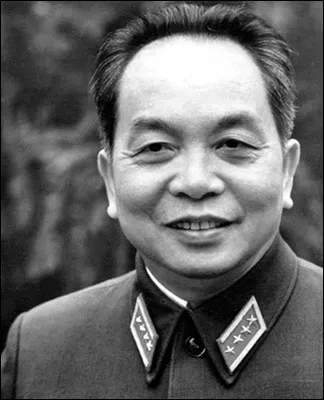

General Vo Nguyen Giap was the Commander-in-Chief of the North Vietnamese armed forces in 1972. He was also the founder of the People’s Army of Vietnam and turned it from a guerrilla into a conventional force. (PAVN)

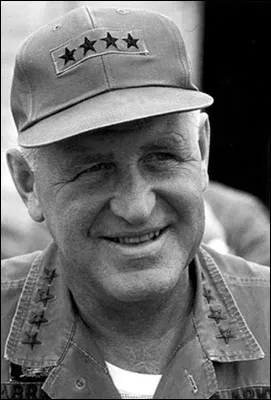

Lieutenant General Abrams succeeded General Westmoreland as head of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) in 1969. (US Army)

A plan to attack the Ho Chi Minh Trail had long been on the Pentagon agenda and six US divisions were supposedly available. However, when the Nixon administration finally gave the green light it was the ARVN – alone with less than half the planned force and far less firepower – that undertook with the brutal task. Furthermore, for the first time the South Vietnamese faced an enemy fighting a conventional battle organized on a Corps level, with tanks, artillery and a strong anti-aircraft gunning umbrella. Consequently, helicopter assaults suffered the worst losses experienced during the entire conflict with 168 destroyed and over 618 damaged. The withdrawing mechanized columns suffered extensively in very difficult terrains along jungle trails.

Anti-war sentiment in the US continued to grow notably after the cross-border raids into Cambodia in 1970 forcing Nixon to accelerate the withdrawal of US troops. Furthermore, the US administration now wanted to withdraw as quickly as possible from a conflict riddled with morale and discipline problems along with racial rioting, fearing this would spread to the whole of the armed forces. The anti-war sentiment also led to great difficulties in recruiting enough officers and specialists to fill all the required posts of a US Army that had grown to 1,512,000 men and women in 1969, with an additional 310,000 USMC personnel. Recruitment problems also hit the elite institutions like the Air Force pilots’ community, where many of them preferred to quit for better paid jobs with airline companies rather than continue to stay with the military. Budgetary constraints due to an increasing economic downturn would also soon force the Pentagon to reduce the size of its armed forces, which in early 1971 had already been slashed by 400,000 men. The troops deployed in South Vietnam were now required for garrison duties in Western Europe, Japan, South Korea and elsewhere, which meant that around 177,000 American soldiers left Vietnam in 1971.

By January 1972 there were only 158,000 US troops left in the country and during that month President Nixon announced that he would withdraw a further 70,000 troops by 1 May. Between February and April 58,000 troops returned to the United States, making it the single largest troop withdrawal of the war, meaning that by the end of March there were only 69,000 US troops left in the country – most in logistical roles supporting two depleted brigades. What remained were army aviation elements as well as a reduced USAF presence providing air support to the South Vietnamese.

The negotiations that started in Paris in May 1968 between the United States and the communist side also bogged down, not due in small measure to the intransigence of the South Vietnamese delegation. However, Washington – in a master-stroke of diplomacy – opened direct negotiations with China, widening the existing gap between Peking and Moscow. This resulted in the now historic trip of President Nixon to Peking in February 1972. The Americans had also approached the Soviets within the cadre of a new détente policy in the Cold War, with the purpose of reducing the number of strategic weapons. Washington hoped that the main supporters of North Vietnam would talk Hanoi into some sort of compromise but this was not the case. North Vietnamese leaders proved to be independent of their bigger communist cousins and skilfully followed their own agenda by playing Moscow against Peking. In doing this they feared that their strained relationship with China would come to an end, so when Hanoi learned that Nixon would come to Peking, the North Vietnamese tried in vain to cancel the summit. However, in order to raise the stakes in the coming negotiations with Washington, the Chinese did not rule out backing the North Vietnamese military against the South. The North Vietnamese Politburo immediately understood the need to act quickly as Chinese support could dwindle.

Since June 1971 General Secretary Le Duan had sought detailed plans for a new offensive in case the negotiations did actually break down. His request initially met resistance because many believed that the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) was not yet ready to engage in such ambitious operations. There were still American residual forces, and more importantly, could the North withstand another air campaign similar to that carried out by the Johnson administration until the end of 1968? Ironically, it was the Chinese–American discussions that led to an ease in tensions in South East Asia, prompting Hanoi to take on the offensive anyway. A new military aid agreement was signed between China and North Vietnam in July 1971 that saw additional deliveries of heavy equipment, including tanks and trucks. Moscow, not wanting to be outdone by the Chinese, decided to send additional tanks, artillery, combat aircraft and considerable surface-to-air missiles in order to upgrade the North Vietnamese air defense system.

Benefiting from the PAVN forming a more mechanized and armored force, Hanoi decided to put Nixon’s Vietnamization policy to its ultimate test by launching a full-scale, nationwide offensive against South Vietnam. The purpose of the campaign, now that nearly all US forces had departed, was to destroy a great part of a perceived fragile ARVN, occupy as much territory as possible and offset gains made by the South Vietnamese in the pacification program. Any opportunity would be exploited to break the South Vietnamese resistance completely and presented to the world as a victory over them and the remaining US troops. Hanoi more realistically hoped to actually grab strategic advantage with this offensive and return to the negotiation table in a strong position. Thus began the fiercest campaign of the Vietnam War in terms of military engagement and length of fighting. The nature of the war had changed dramatically, evolving from a guerrilla one into a conventional conflict that set the trend until the fall of Saigon three years later. The North Vietnamese would learn the hard way how to conduct mechanized operations against a better organized southern force.

The ARVN would always fight proudly and often heroically with the help of US airpower and a small number of American advisors, but due to the fact that almost all US ground troops had departed by now, these years of the war are often overlooked. This book remedies that by not only looking at American archives but also Vietnamese sources. The role played by US airpower against North Vietnam (Operation Linebacker and Linebacker II) is outside the scope of focus here which only deals with ground operations taking place in South Vietnam. These air offensives are noted by a brief summary so the reader can gain a strategic picture of the campaign. Geographically the war was mostly fought on three distinct areas: the northern part of South Vietnam, where the North Vietnamese attacked across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and from Laos; the Central Highlands; and the area north of Saigon, with strong guerrilla activity in the Mekong Delta Area. For clarity, each battle area is treated separately even if many battles are taking place simultaneously.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

THE ALLIED FORCES

The South Vietnamese forces

The South Vietnamese armed forces was set up during the French Indochina War and underwent great reorganization after the Geneva Accords, which saw the splitting of Vietnam into two distinct states. The military was restructured by grouping the units deployed in the northern part of the country and by integrating some French colonial troops of Vietnamese origin. After facing a series of internal rebellions against groups of non-communist dissidents, who rejected the rule of the new Ngo Dinh Diem regime – such as the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai religious sects, and the Binh Xuyen – the ARVN was streamlined. With aid from the American Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) the ARVN became a more conventional force to withstand an invasion from North Vietnam. However, the ARVN was underprepared to cope with the communist guerrilla threat and the situation worsened due to political instability following the coup that overthrew President Diem in November 1963. This was followed by several other coups which drew America’s hand and finally forced them to intervene in the conflict in 1965. With this, the nature of the war changed radically, with the Americans taking over the majority of main operations, casting aside the ARVN and its politicized inner-core. The Americans had never fully integrated the ARVN into a combined allied supreme headquarters like they had during the Korean War. Instead, they set up the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) which would work in parallel with the ARVN Join General Staff (JGS).

Constitutionally, the supreme commander of the South Vietnamese armed forces was the President of the Republic. He was advised by the Defense Minister, the National Security Council, and the Central Pacification and Development Council on military and strategic issues. The JGS was in theory the body charged with implementing war strategy and conducting military operations, through combining the efforts of the ARVN, the Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) as well as the VN Navy. In reality, due to the nature of South Vietnamese politics, it was President Nguyen Van Thieu who alone had the final say. Being the strongman of South Vietnam for nearly seven years, Thieu had succeeded in restoring stability to a very volatile political scene. Nevertheless, he remained cautious on military and strategic issues – he rarely shared his views with his subordinates fearing they would expose him to his political rivals. Every military action had domestic implications and all decisions were taken by the President within a small circle of appointees and loyal followers.

Most of his inner-circle were generals who had supported him during various coups that had rocked the country in the early 1960s, and collectively were part of what was called the ‘Delta Clan’ from the days of serving with him in the Mekong Delta Area. Even down to the provincial chief level, every post held by ARVN officers was decided by Thieu with the aforethought of averting coups. He dealt directly with the four military regional Corps commanders who also exercised authority over the province chiefs. Each Corps commander then had wide-reaching powers within his military region and acted autonomously as local operational commander – they answered only to the President. However, these power-hungry ‘pillars of the regime’ would often not coordinate their operations with the other attached units when they were deployed in the field, which made strategic operations very difficult. Further complicating things was Thieu’s tendency to take tactical decisions that overruled the local commanders, without always informing them.

The M41A3 formed the backbone of the ARVN armored units but was now clearly outmatched by the North Vietnamese T-54. (US Army)

The reality was then that little coordination existed at national level and the JGS, placed under the command of Lieutenant General Cao Van Vien, had only an advisory role and were tasked with budgetary and manpower tasks. Lieutenant General Vien rarely, if ever, interfered with Corps Commanders’ operational plans and decisions except for cross-border operations or when the General Reserve units were involved. The ARVN High Command was plagued by incompetent and politically appointed leaders which drew from a small pool of those that had been cast aside and confined to mere pacification operations. ARVN commanders had few opportunities to hone their military skills and whilst the VNAF and the VNN had developed into modern entities, the ARVN commanders had no grasp of how to exploit them. All of these factors combined to limit the ARVN command structure, but ironically one of the biggest problems they faced was the actual Vietnamization program itself. At the beginning of the conflict, the US forces quickly placed the ARVN into support roles dealing with pacification tasks only, which meant they were often outgunned by the enemy and relegated to what were then viewed as secondary roles. Therefore, South Vietnam’s armed forces missed out on several years’ worth of development and combat experience that would have greatly increased their capabilities – even if they did perform relatively well during the infamous Tet Offensive of 1968.

Unfortunately then – even if they were not fully prepared and well-structured – it was still the South Vietnamese who were called to bear most of the fighting at a rate that they had difficulty to cope with. Initially it was envisaged that their ‘burden’ would run from 1968 to 1974 with a strong US ground force supporting the ARVN, but as things accelerated they were forced to undertake harder tasks. Initially they were only called upon to root the Viet Cong but this grew to coping with North Vietnamese regulars and then offensives into Cambodia and Laos – and now to totally replace the Americans. However, the lack of competent officers stagnated the whole process and the envisaged speed of battle-adaption stalled several times over. The problem lay in the fact that the ARVN was competing with other services in recruiting the best candidates, notably with the Navy and particularly the Air Force. Consequently, by 1969 nearly half of the infantry battalions were commanded by officers two ranks lower than the required level. In order to solve this recruitment problem it was decided to increase the intake of candidates at the Reserve Officer School of Thu Duc – which promoted some 11,000 officers between 1968–1969. The school offered an accelerated syllabus of only one year in comparison with the four years required at the National Military Academy of Dalat.

The South Vietnamese Signal Corps stand proud during the Armed Forces Day parade, on 19 June 1971. Pictured is new communication equipment and radio antennae mounted on a Japanese Toyota DW 15L in the foreground with US M35 trucks in the background. (ARVN)

However, even when around 1,000 discharged officers were also called back to fill the void, it only partially negated the combat losses, and those officers discharged for corruption. A promotion policy also saw around 2,653 middle rank officers enlisted, but statistics still showed that 40 percent of these were not posted to operational units but served in various civilian administrative structures at provincial and district levels. In fact, it wasn’t until the end of 1970 that a structured program was launched. With this, 12,000 ARVN officers were sent to the United States for advanced training at a number of military schools – including the US Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

By the end of 1971 the situation had slightly improved, but a third of infantry battalions were still commanded by captains, whilst most of the ARVN officers had held their command for less than a year. By early 1972 the overextended ARVN disbanded 15 infantry battalions in order to ‘spread’ the number of available officers, and under American pressure it was also decided to set up a Command and Staff School as well as a Political Warfare School in 1969 – in order to improve the professional hierarchy level of the ARVN. The National Defense Academy offered comprehensive one-year training in academic matters relating to strategy -and five classes graduated from it between 1968–1973 – but again, less than 10 of the 111 colonels and generals that successfully passed-out were later placed in key command posts. In fact, in the much politicized command structure, it was still President Thieu who nominated every officer irrespective of their credentials.

Even so, the South Vietnamese armed forces did see c...