![]()

CHAPTER 1

BACKGROUND

On 30 March 1972 the South Vietnamese positions along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) – that separated North Vietnam from the South – were suddenly shelled by hundreds of heavy guns and multiple rocket launchers (MRL). Shell-shocked soldiers in a series of outposts along the former ‘McNamara Line’ scrambled out of their bunkers only to be then met by the accompanying onslaught of the regular North Vietnamese divisions – supported by hundreds of tanks that smashed through their defensive lines. Thus began one of the fiercest campaigns of the Vietnam War, but also one of the less well-documented, as most American ground troops had been withdrawn following the introduction of the ‘Vietnamization’ policy which aimed to hand the South Vietnamese greater war-effort responsibilities. The nature of the war itself at this point had changed dramatically – evolving from a guerrilla one into a conventional conflict that set the trend until the fall of Saigon three years later. The North Vietnamese would learn the hard way how to conduct mechanized operations against a far better organized southern force (the previous volume in this series The Easter Offensive – Invasion across the DMZ looks in great detail at the context of the fighting, along with the growth of both armies: The South Vietnamese Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and the People Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in the North).

The campaign pitted two sides that had both been significantly modernized and expanded, with the South Vietnamese – aided by America – between 1969–1972 increasing the size of its military forces from 825,000 to over one million – with 120 infantry battalions in 11 divisions, supported by 58 artillery battalions, 19 armored cavalry regiments, and many engineer and new tank squadrons. After years of neglect, Washington also gave top priority to equipping the ARVN with over one million M16 rifles being delivered, as well as 12,000 M60 machine guns; 40,000 M79 grenade launchers, 790 4.2inch (107mm) mortars, 10,000 radios and 20,000 trucks. In addition, to confront the North Vietnamese T-54s, around 56 M48 medium tanks were also delivered by 1972.

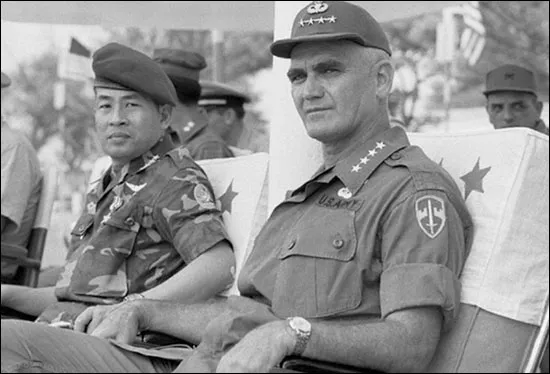

Lieutenant General William Westmoreland, Commander of the MACV, and Lieutenant General Cao Van Vien, Chief of the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff, sitting side by side. The much politicized ARVN turned the JGS into a mere advisory, rather than an operational, command. The most crucial military decisions remained in the hands of President Nguyen Van Thieu and his four Corps commanders. (US Army)

By now, the regular force made up less than half of the South Vietnamese forces (535,000 men) being complemented by Territorial Forces which played a key role in the pacification program. They included 282,000 Regional Forces (RF), organized into battalions and assigned to military provincial control, and 243,000 Popular Forces (PF) organized into platoons and assigned at district level. These RF/ PF soldiers were now also re-equipped with modern M16 rifles and M79 grenade launchers, but their main task was only to deal with local Viet Cong because, when facing regular PAVN units, they were usually not up to the challenge. Finally, there were more than 500,000 within the People’s Self-Defense Forces (PSDF) but these militias were only part-time guards operating at village and hamlet levels, and armed with Second World War M1 rifles and carbines. Tactically, the divisions were grouped within four Corps and each Corps was in turn assigned to a particular Military Region (MR). The 1st Corps operated in MR I which covered the northern part of the country, from the North Vietnamese border to south of Da Nang; the 2nd Corps was assigned to the MR II, covering the Central Highlands and the coastal area between Qui Nhon to Phan Rang; the 3rd Corps operated within the MR III, covering the area around Saigon; and finally, the 4th Corps served in MR IV, containing most of the Mekong Delta Area.

The Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), which was set up as an advisory body to the ARVN, became increasingly less influential with the arrival of US ground units. However, as the war progressed the importance of the MACV advisory assets grew again and advisory structure very closely paralleled that of Vietnamese military command and control organization – with the headquarters providing the advisory function to the ARVN JGS. Under this, a Regional Assistance Command (RAC) was assigned to each of the four ARVN Corps-Military Regions, and under the US RAC Commander (usually a Major General) were two types of advisory teams – province advisory teams and division advisory teams. Each province was headed by a South Vietnamese colonel, and his American counterpart was the province senior advisor who controlled the District and Territorial Forces advisory teams. The province team was responsible for advising the province chief in both civil and military aspects of the ongoing pacification and development programs. In addition to province advisory teams, there was a Division Combat Assistance Team (DCAT) deployed to each South Vietnamese infantry division. Elite units, such as the Airborne Rangers and Marines, were generally organized along the same lines as regular ARVN units, but as American forces began withdrawing from the country, the number of advisors also dwindled. Thus, they now only operated at divisional and regimental levels apart from in the Marine Division where they continued at battalion level. By January 1972 there were only 5,416 American advisors in the whole of South Vietnam.

Different to the US–South Vietnamese dual command structure, the North Vietnamese High Command was centralized around the Communist Party Political Bureau. One of its leading figures was Senior General Vo Nguyen Giap, Commander-in-Chief of the PAVN since its creation. He also held the post of Defense Minister and President of the powerful Central Military Commission. He is seen here, second from left in civilian clothes, during a 1971 visit to the Soviet Army Malinowski Armored Academy of Moscow, where many North Vietnamese officers attended courses. (Albert Grandolini Collection)

In North Vietnam, since the failure of the Tet Offensive in 1968, the main PAVN units had also evolved into a modern mechanized force and were themselves now being greatly supported, but by the Soviet Union and China – who had both delivered heavy artillery and tanks between 1970–1971. However, the motorization phase did not run smoothly because many North Vietnamese divisions could not be upgraded and trained on schedule as they were already deployed in the field, and the PAVN then found it difficult to create units ready for the new form of mechanized and combined arms operations. Mobile training teams were thus sending units forward whilst other regiments or divisions rotated back into North Vietnam for refitting. Yet, despite all these difficulties, the PAVN modernization process continued unabated and led to a force of some 16 divisions and four armored regiments by early 1972. This force of 433,000 men and 655 tanks was also supplemented by around two million men and women, including 870,000 light infantry, which belonged to the Militia Command. Also, some 104,000 ‘regulars’ and 26,000 guerrillas officially belonged to the Viet Cong, who were officially independent from the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), the military wing of the National Liberation Front (NLF) – a fictitious designation allocated to the Viet Cong for propaganda purposes. Within the Viet Cong itself though, morale was faltering and Hanoi was forced to bolster its ranks whilst the COSVN had become nothing but a Forward Command Post of the PAVN that needed constant support from the B-2 Front. However, the PAVN expansion process continued throughout the Easter Offensive despite huge losses and the number of regular battalions rose from 149 in 1969, to 285 in December 1972. Some 3,000 Soviet advisors and technicians also supported the expanding PAVN along with dozens of Chinese, Cubans and other Warsaw Pact personnel.

However, for all the North Vietnamese expansion and modernization, the South had one clear superiority – its air capabilities. The Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) had more than doubled its size under guidance from America, increasing to nine tactical wings; 42,000 personnel; and nearly 1,000 aircraft, including A-1 and A-37 ground attack aircraft; and F-5A fighters – but most at all, the South Vietnamese could still count on vital American air support from within the country, from Thailand, or reinforced from the Pacific and the United States itself. The role played by US airpower against North Vietnam (Operation Linebacker and Linebacker II) is outside the scope of focus here, which only deals with ground operations taking place in South Vietnam. These air offensives are noted by brief summaries so the reader can gain a strategic picture of the campaign.

For the first time the North Vietnamese planned a nationwide offensive by deploying a great number of armored vehicles, with more than 700 tanks and self-propelled guns engaged, most being the T-54s and Type 59s. (PAVN)

North Vietnam was administratively divided into four military regions, whilst South Vietnam was organized into five military regions and subsequently into Military Theaters (Fronts): the B1 Front covered the coastal zone expanding from Da Nang to Cam Ranh; the B2 Front covered the COSVN operational area; the B3 Front covered the Central Highlands area; the B4 Front covered the DMZ to the Hai Van Pass, south of Hue; and the B5 Front covered the DMZ itself and the southern part of North Vietnam. Geographically the war was mostly fought on three distinct areas: the northern part of South Vietnam, where the North Vietnamese attacked across the DMZ and from Laos; the Central Highlands; and the area north of Saigon, with strong guerrilla activity in the Mekong Delta Area. For clarity, each battle area is treated separately even if many battles are taking place simultaneously. Also, after devoting much of Volume 1 to the battles taking place in the northern part of South Vietnam in the area between Hue, Quang Tri and the DMZ, this volume focuses on the operations in the sector north of Saigon as well as in the Central Highlands.

These PAVN T-34-85 tank crews take a break with the workers and families at a collective farm following a training exercise there in 1971. (PAVN)

![]()

CHAPTER 2

HANOI’S STRATEGIC SURPRISE

The North Vietnamese invasion across the DMZ caught US and Vietnamese commanders completely by surprise. They were indeed fully aware that Hanoi was planning a full-scale offensive but no-one could agree on its date nor target. The previous months had certainly seen an upsurge in North Vietnamese operations but a consensus opinion was formed amongst the intelligence communities that Hanoi would do nothing more than attack the Central Highlands On 29 April 1971 it was even hypothesized that Hanoi would wait for the US presidential election of 1972, or even until all US troops had left the country, before attempting anything. Also, the intelligence organizations consistently underestimated the new capacity of the PAVN in both motorized and armored warfare, and had therefore been unable to ‘predict’ North Vietnamese intentions for months. Even the commander of the MACV, General Creighton W. Abrams, shared the opinion of South Vietnam President Nguyen Van Thieu, that Hanoi would wait before attacking.

South Vietnamese intelligence was also weakened by the lack of a centralized structure even though in theory Lieutenant General Cao Van Vien was in command of the ARVN Joint General Staff (JGS). However, because military and political systems were interwoven, all power was in the hands of President Thieu – and it was the President himself who directly dealt with the four Military Regions and Corps commanders. Therefore, even if the stumbling intelligence agencies had been warned of an imminent threat, the lack of coordination and cooperation would have hindered any ARVN response. Highlighting this is the fact that, despite an intense air interdiction campaign along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the North Vietnamese succeeded in deploying a great part of their army almost undetected. It was actually PAVN Commander-in-Chief, Senior General Vo Nguyen Giap, who decided to halt their own advance because of logistical difficulties and the threat of US airpower. With all this going unnoticed, confidence built and led to Senior General Giap’s decision to send the main thrust of his campaign across the DMZ due to its location just over the North Vietnamese border. For both political and military reasons, Senior General Giap decided to open two other fronts, first to force the ARVN to disperse its limited central reserve made up by the Airborne and Marine Divisions, and second to tie down the other regular forces. Politically, he wanted to occupy as much territory as possible so North Vietnam would be in a strong position at the ongoing negotiations in Paris. Cleverly, Senior General Giap had also deduced ARVN ‘underestimation’ of the PAVN and therefore that they would most likely expect an attack across the Central Highlands because this was the most logical attack point – being the second most important Front after the DMZ itself – so he did the exact opposite, attacking at the heart of the ARVN. To do this he heaved the PAVN directly into ARVN Military Region III, which encompassed the Saigon area, raising the stakes which he knew would catch the Americans and ARVN by surprise. He ideally wanted to seize a provincial capital close to Saigon and make it the seat of the COSVN and thus for the Viet Cong and of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) – creating a stronghold where they geographically faced, and could attack, Saigon.

The North Vietnamese offensive goaded the Nixon administration to resume the air campaign, which had been suspended since November 1968. These F-4Ds from the 435th TFS of the 8th TFW head North for another mission. (USAF)

The organizational drive for this campaign was massive and the reinforcement of the units within the B2 Front took top priority. The North Vietnamese requested an additional delivery of some 9,000 trucks from the Soviet Union, and 3,000 more from China to fulfil their battle needs. This effort was supervised by the Logistical Group 559 that oversaw the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which transferred enough equipment for the four main divisions at the B2 Front. From October 1971 to March 1972, some 47,500 tons of supplies were delivered, including 19,000 tons of rice. It was estimated that these deliveries would sustain troops for a three-month mechanized campaign, whilst the rice would last three months longer as they approached the gates of Saigon.

The American response

Initial US response to the offensive across the DMZ was confused and lackluster, and the Pentagon was not unduly alarmed with both the US Ambassador and General Abrams both out of the country. Also, President Nixon’s first reaction to consider a three-day attack by B-52 bombers on Hanoi and Haiphong was considered too strong by his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, who convinced the President to reconsider. The Americans were in somewhat of a stalemate because they did not want to jeopardize the ongoing n...