![]()

Section 1

The Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 Reflects a Bigger Fundamental Imbalance

Introduction

Volumes have been written about the financial crisis—the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the government’s bailout of AIG and the auto industry, the failure of the Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), and a number of other domestic financial institutions caught in the grip of a recent economic catharsis. Most of the published analyses tend to deal with either the adverse direct consequences of the crisis or the regulatory failure that allowed the problems to develop in the first place. The social consequences of the crises seem to have received the majority of the media attention. The press focused primarily on the decline in home prices, household wealth, and the resulting rise in structural unemployment in both the construction industry and in the overall economy.

The economic community has also analyzed the social consequences of the crisis, but most studies have tended to look into the effects on bank lending, the linkage between the contraction in credit and the nature of the downturn, and the recovery. Although it is understandable why the analysis of the crisis has gone in this direction, I am afraid people may be missing the forest for the trees. What’s lacking—the big-picture “forest,” in this case—is the fundamental shift in the economy from excess demand to excess supply and from inflation to credit cycles. Moreover, the perceived regulatory failure that led to the crisis resulted in the Dodd–Frank legislation, which is in the process of fundamentally altering the way banks and the financial services industry will function for years to come. The so-called “Volcker Rule” restrictions on investment banking and the SEC’s decision to change the rules governing the net asset value of institutional prime money market mutual funds are additional examples of the regulatory response to the financial crisis, and volumes have been and will continue to be written on these topics.

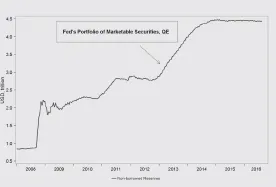

The growth of household leverage and the lax banking standards that allowed the real estate bubble to inflate have also been studied by academics, policymakers, and the press. This analysis has also been used to support the regulatory reforms that have been advanced. The mismanagement of the auto industry and its financing arms have been well documented by the press; but they’ve remained largely ignored by economists because the Obama team chose to rescue the industry in light of its vital role in the American economy. The manner in which government policymakers reacted to the crisis is another popular topic with market commentators, economists, and the financial press. The Fed’s cutting short rates to near zero was followed quickly by targeted liquidity measures; these actions were cobbled together in the midst of the financial crisis to address specific market failures as well as analyses in detail by both the public and private sectors. These programs were eventually replaced by the Fed’s large-scale asset purchase program, dubbed “QE,” and it’s likely the debate over the value of this initiative will rage for years to come.

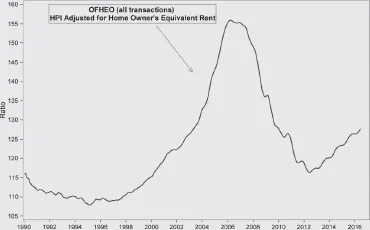

fig 1.1

Source: Macrobond, Mizuho Securities, NAR, Census Bureau, FHFA, BLS

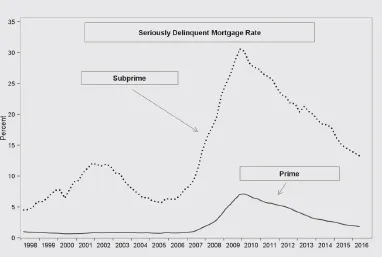

fig 1.2

Source: Macrobond, Mizuho Securities, Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA)

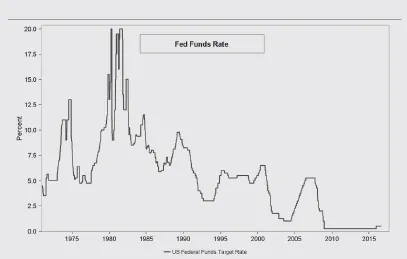

fig 1.3

Source: Macrobond, Mizuho Securities, Federal Reserve

fig 1.4

Source: Macrobond, Mizuho Securities, Federal Reserve

Almost nothing has been written, however, about how, why, and when the seeds of this crisis were sown. The evolution of the economy, markets, central banking, and government intervention that combined to create the environment in which excess leverage was allowed to be accumulated needs to be assessed to obtain a clear understanding of how the Great Recession and its disappointing recovery came about. It is this excess leverage that eventually crushed the housing, auto, and banking industries. Despite all the new regulations, the economic analyses, financial commentaries, and press coverage of the crisis, unless we understand what precipitated this explosion in leverage and make the appropriate regulatory and policy adjustments, we are likely to repeat the same mistakes again.

To address this deficiency, the analysis in this book will trace the roots of the excess leverage that prompted the financial crisis back to the political and economic climate that emerged immediately after WWII. I will follow these roots through the geopolitical and economic decisions prompted by the Cold War; and I will consider how the weakening of the negotiating power of the unions, the emergence of environmental regulation, and the oil embargoes altered the nature of global competition to the detriment of domestic manufacturers. I will also look at how the Fed’s battle against inflation in the 1980s accelerated the major shifts in manufacturing, banking, and financial markets. The surging dollar, the institutionalization of wealth, and the globalization of wealth hastened the growth of the emerging economies. The excessively high short-term interest rates built on the high real rates that followed the war and altered the perceptions of sustainable returns. These developments ultimately shifted the balance between supply and demand in favor of excess supply.

In the early stages of this period, the natural tendency was for excess demand to dominate the business cycle. Since the 1990s, however, the shift to excess supply has tended to dominate. The result has been a dramatic decline in the nominal cost of funding, which, when combined with the blind pursuit of double-digit returns on a threeto six-month basis, has resulted in an economy built on excess leverage and focused on cost cutting and financial engineering to drive earnings. In fact, since the early 1990s there have been only three business cycles, and all have been associated with a run-up in leverage that eventually burst, forcing a deleveraging or, in other words, a credit cycle. Two of these have been consumer and/ or housing related, including the latest, which economists call the Great Recession. The credit cycle experienced in 2001 and the dot-com downturn were the result of a forced corporate balance sheet restructuring. If nothing is done to alter domestic competitiveness and to reestablish a better balance between supply and demand by creating good-paying jobs and/or pulling expectations back in line with reality, the next credit cycle could be even deeper than the past three.

Sowing the Seeds of the Imbalance

Demand Pull

The period immediately following WWII was dominated by a confluence of factors, all of which contributed to creating an extended period of excess demand. To avoid the economic and political mistakes made after WWI, the period of repression, which immediately followed the war, eventually morphed into efforts to rebuild Germany and Japan. It became clear after WWII that the way to win peace was through improved quality of life for citizens on both the European and Asian continents and not by extracting never-ending reparations. This drive to reverse the ravages of the war created a surge in demand for everything American and American-made. The fact that our domestic manufacturing and agricultural bases were left not only intact but also greatly expanded, and even more productive, thanks to the war effort, allowed profit-motivated companies to steer the political agenda and seek out beachheads in Europe and Asia as a means of expanding and securing their place as powerful competitors in these regions.

The returning GIs and the programs designed to reintegrate them into society sparked a tremendous surge in demand for consumer products, housing, transportation, and education services. The technological advances pioneered during the war were quickly adapted for peacetime applications, and the explosion in new and existing industries led to a spike in the demand for labor. After an initial period of transition from a wartime to a peacetime economy, real GDP surged and resulted in an explosion in the middle class. High-paying jobs in construction and manufacturing were being created while federal, state, and local governments rushed to build the infrastructure to meet these demands. The rapid expansion of the interstate highway system is an example of this effort to satisfy the demands of a rapidly expanding and more affluent economy. An explosion in household formations and live births also played a big part in shaping the economy in the years following the end of the war. The baby boom, in fact, is one of the most important developments of the postwar period, as it helped set in motion a sustained period of excess demand for goods and services.

Roughly two years after WWII ended, the Cold War began. This set in motion an arms race between the Soviet Union and the West (led by the United States). The industrial policies undertaken in the name of maintaining military preparedness on multiple fronts, as well as permanent military bases in Western Europe and in several countries in Asia, led to rapidly expanding excess demand. President Eisenhower’s threat to nationalize the steel industry in the 1950s is an example of how the government and the establishment of a permanent military industrial complex helped to increase aggregate demand and shifted the balance toward a position of excess demand.

Although the Cold War standoff dominated the military focus in Europe, the struggle against Communism expanded into an all-out military conflict on the Korean peninsula and in Southeast Asia, increasing the public sector’s demand for both goods and services. At exactly the same time, Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” experiment and the civil rights movement were increasing the demand for government involvement in expanding social services. This confluence of factors stretched the economy’s ability to accommodate this competing demand for a fixed pool of resources.

Strained political relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors boiled over into outright war, and tensions have remained (other than for a short period immediately after the 1978 Carter peace accords were signed between Israel and Egypt). The United States’ support for Israel helped to instigate two embargoes by oil-producing Arab nations between 1967 and 1974. These oil-producing nations not only nationalized production facilities that had been built by foreigners on their soil, but they also colluded with other oil-producing nations—OPEC—to fix the price of oil. Crude oil prices, in fact, quadrupled by the end of 1974, rising to over $12 a barrel. The political tensions in the Middle East did not end with the seven-day Yom Kippur War. Instead, the Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War quickly followed, and crude oil and refined prices moved decidedly higher. Rising crude oil prices quickly rendered a large portion of domestic manufacturing obsolete. This widened the imbalance between demand and supply and put significant upward pressure on prices.

President Kennedy’s race to put a man on the moon is another example of how the Cold War influenced the economy of the postwar period. The resulting technological advances sparked innovative new products and new highwage middle-class jobs, and they helped extend the period of excess demand. Another such example was President Reagan’s “Star Wars” missile defense initiative. During the early part of the Cold War, an aggressive push to contain the spread of Communism beyond China led to back-to-back wars in Korea and Vietnam. These long and costly military conflicts, when combined with the rapid expansion of the arms race with the Soviet Union, led to a multiple expansion of the defense industry and the growth of the military industrial complex. The defense industry’s demands on domestic manufacturing, natural resources, and skilled labor widened the spread between demand and supply evident in the economy.

Cost Push

The surge in demand for goods and services increased the power of unions as the economic cost of worker unrest increased dramatically and companies embraced collective bargaining as a way to keep factories running. The upward drift in inflation during the first 40 years after the war was amplified in the late 1960s and 1970s by a series of environmental and safety regulations that were imposed on domestic manufacturers. Toxic-waste laws implemented during this period, such as smokestack emissions limits, tailpipe emissions standards, and water pollution laws, added significantly to the cost of doing business; yet they added no benefit to the bottom line. Workplace safety regulations and auto safety laws were also being implemented; these, too, added to the costs of producing goods and services. Health care insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid were all introduced early in the postwar period and then expanded rapidly, resulting in a growing share of the economy dedicated to health services. Adding further to the inflationary pressures were the Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) clauses built into labor contracts and into Social Security benefits early in the postwar period when the cost of such agreements was perceived to be negligible. Geopolitical developments pushed oil prices even higher to $35 per barrel from essentially $14 per barrel in 1981.

Making matters worse were the industrial policies employed by the US government between 1973 and 1981. Specifically, the oil price controls imposed on domestic oil producers significantly curtailed exploration and production, increasing dependence on higher-cost imported oil. Higher energy costs not only increased the cost of manufacturing, but they also rendered vast amounts of the domestic capital stock obsolete, which in turn contributed to the excess demand situation.

The costs associated with these developments were passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices, which led to rising wages and the establishment of a wage-price spiral. Rising prices squeezed real household income and the result was increased wage demands by labor unions. The excess demand environment weakened management’s ability to resist, and cost-push inflation compounded the problem generated by demand-pull inflation pressures. Inflation ratcheted upward of 14% in the late 1980s from just 1.5% in the 1950s.

Shifting Dynamics of Supply and Demand

The great inflation period of the late 1970s and the Reagan supply-side revolution played key roles in moving the economy from excess demand to excess supply. The Reagan tax cut was justified under the theory that lower tax rates boosted investment and created noninflationary growth. We can argue all day about the empirical support for the Laffer curve; however, the resulting increase in government bonds that was associated with the reduction in marginal tax rates led to a sharp rise in real interest rates. A higher real rate and a double-digit inflation premium resulted in not only long-term government bond rates above 14%, but also the Fed’s shift in monetary policy from interest rates to non-borrowed reserves targeting.

Targeting the money supply resulted in a dramatic increase in short-term rates. In fact, the federal funds rate actually traded up to 26% one night. The Volcker tightening inverted the yield curve as short rates rose to a high of 20% in March 1980. This dynamic accelerated the institutionalization of wealth as investors pulled money out of passbook savings accounts and bank CDs and funneled these proceeds into money market mutual funds. These relatively new investment products promised both high returns and liquidity, leading to a multiple expansion in the mutual fund industry. As the economy slumped into the 1981–1982 recession and inflation began to slow, the Fed began to cut rates and the financial services industry shifted gears to take advantage of new opportunities created by the institutionalization of wealth.

Mutual fund managers reacted quickly to the declining rate environment by talking up the benefits of their equity and bond mutual funds. The logic was simple and straightforward. Mutual fund managers could search out companies that had bloated management, excess staff, and inefficient collections of business and use shareholder activism to increase the return to investors in their funds. The game plan was to reward companies whose management focused on achieving strong quarterly earnings targets through cost cutting, strategic M&A, jettisoning underperforming product lines and businesses, and, when necessary, using financial engineering to boost earnings per share.

As money managers ran out of easy domestic companies to restructure, the focus began to shift in the 1980s to overseas companies, and the globalization of the financial market kicked into high gear. Companies and CEOs were rewarded for shifting production overseas or creating strategic...