![]()

III.

SCALES AND KEYS

![]()

Chapter 5:

MAJOR SCALES AND KEYS

NEARLY ALL OF the music in the world is built upon what we call a scale, a collection of five to eight pitches arranged in either ascending or descending order. There are many different types of scales used in world music. Although many date back to antiquity, we know the exact origin of only some. While rhythm and pitch are the most basic, fundamental elements of music, the scale is what is what really lets us create music. In modern Western music, scales consist of eight pitches arranged in patterns of whole steps and half steps. There are two main types of scale in Western music: major and minor. Together, they represent what is known as tonal music.

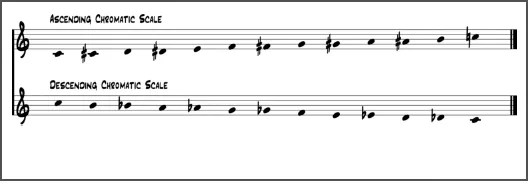

The octave can be divided into twelve equal half steps. This is called the chromatic scale, and it essentially represents all pitches. Ascending, the chromatic scale is spelled with sharps; descending, it is spelled with flats. (Remember the enharmonic equivalents we learned about in Chapter 3.) Figure 5.1 shows both the ascending and descending chromatic scale. The scale starts on C in this example, but it can start on any pitch. If you compare the chromatic scale to the piano keyboard, you'll notice that it contains all of the black and white keys within an octave. The chromatic scale is seldom used in the composition of Western music, but it serves as an important starting point for the development of the major and minor scales that are prominent in Western music.

Figure 5.1. Ascending and descending chromatic scales

Although most scales are some combination of whole and half steps, occasionally a scale will use an interval larger than a whole step. Scales give music its particular color or flavor, because the unique combination of intervals is then transferred to the melody and harmony. The major and minor scales are both seven-pitch scales containing five whole steps and two half steps, yet they sound strikingly different! In order to understand tonal music, you must remember that the melodic and harmonic patterns of music are the reflection of a pattern of intervals, the scales.

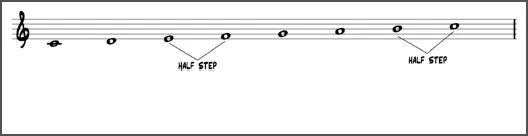

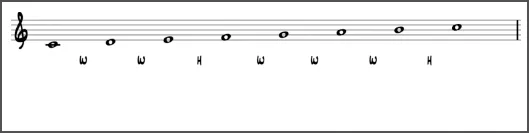

The major scale is a seven-pitch scale that consists of five whole steps and two half steps, with the half steps occurring between the third and fourth tones and between the seventh and first tones. When a major scale begins on the pitch C, the scale is simply all of the white keys played sequentially within the octave. In Figure 5.2 you can see that the half steps in a C major scale fall between E and F and between B and C. Compare the musical notation to the keys of a piano, and you'll notice that E and F and B and C are white keys that are immediately adjacent to each other.

Figure 5.2. C major scale

The major scale employs a particular pattern of whole steps and half steps: whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half. This pattern remains true regardless of which pitch you begin on. What gives the major scale such a distinctive, recognizable quality? First, there is the establishment of the tonic pitch, which is the foundation of the scale and—by no coincidence—the starting pitch of the scale. You might also think of this as the “home” pitch. The half step between the seventh and first tones of the scale creates a particular pull toward the tonic, and all other pitches want to find their way home to the tonic as well. The seventh tone is called the leading tone because it always leads toward the tonic. In many ways, this works like “aural gravity,” with the tonic acting as a large object pulling the sur rounding objects toward it.

Figure 5.3. The pattern of whole and half steps that comprise a major scale

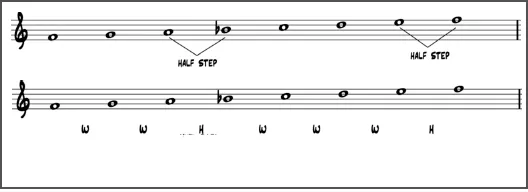

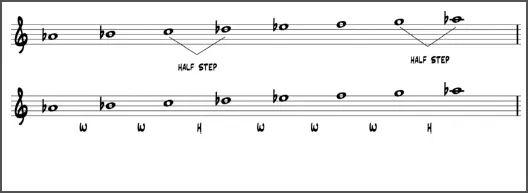

As mentioned above, a major scale can start on any of the pitches of the chromatic scale, and if the pattern of whole steps and half steps remains intact, the result will still be a major scale. For example, if the scale were to begin on the pitch F, it would be necessary to add a flat to the B in order to create the half step between the third and fourth tones and thereby maintain the pattern (Figure 5.4). Similarly, an A-flat major scale requires four flats (one of which is simply to lower the A to A-flat). Figure 5.5 shows the pattern of whole steps and half steps required to make an A-flat major scale, as well as the necessary accidentals.

Figure 5.4. F major scale showing the pattern of whole and half steps

Figure 5.5. A-flat major scale showing the pattern of whole and half steps

Remember that as long as you keep the pattern of whole steps and half steps intact, you can form a major scale beginning on any pitch. The other important piece of information when creating a scale is that the letter names of the pitches must always be sequential. For example, the A-flat major scale in

Figure 5.5 uses the pitches A

, B

, C, D

, E

, F, and G. Even though we can enharmonically spell B

as B# or D

as C#, we must use a sequential ordering of the pitches' letter names.

In the...