Nguyen T. Thai and Ulku Yuksel

INTRODUCTION

Choice overload (CO) is a phenomenon whereby choosing from large assortments results in negative consequences and perceptions (Chernev, Böckenholt, & Goodman, 2015; Scheibehenne, Greifeneder, & Todd, 2010). However, most empirical studies reporting this phenomenon have been conducted in the context of everyday retail products such as consumables like chocolates, jams, and crackers, to name a few. Despite the evidence of the presence of CO effects in physical products, such empirical evidence is less common in other areas, such as in complex service contexts (Chernev et al., 2015; Scheibehenne et al., 2010). To explain this lack of evidence, one could argue that CO studies often rely on retail products instead of services because the implementation of experimental designs is more convenient. Alternatively, others contend that CO effects do not exist in complex service contexts because high levels of financial or emotional risks encourage people to become highly involved in the decision-making process (Sirakaya & Woodside, 2005), and thus, they want more choice. Therefore, the question regarding the existence of CO in complex service contexts has yet to be answered.

Within the tourism literature, evidence of CO effects is also very limited (McKercher & Prideaux, 2011; Rodríguez-Molina, Frías-Jamilena, & Castañeda-García, 2015), except for three studies (Park & Jang, 2013; Thai & Yuksel, 2017a, 2017b). Tourism researchers have not actively engaged in the academic conversation as to whether tourists experience CO during their vacation decision-making processes. The lack of research about CO effects in tourism is surprising because tourists usually encounter numerous options when making travel decisions (Decrop & Snelders, 2004; McCabe, Li, & Chen, 2016). For that reason, tourism researchers should investigate CO effects because understanding how tourists make choices from large assortments will challenge the assumptions embedded in previous, general tourist decision-making models, that tourists are rational decision makers and utility maximizers (Decrop & Snelders, 2004; McCabe et al., 2016).

This book chapter applies current understandings of CO from psychology and marketing to tourism research. Specifically, the chapter builds on Chernev et al.’s (2015) conceptual model of the impact of assortment size on CO. Chernev et al.’s (2015) model integrates numerous factors that eliminate or mitigate CO effects as there has not been consensus among previous studies in explaining clearly when CO effects occur. This book chapter extends Chernev et al.’s (2015) model by adding another moderator group; that is additional factors eliminating CO effects. Then, the chapter applies the modified model to recommend five groups of solutions for tourists and travel advisors to help their customers avoid CO effects: reducing decision task difficulty, reducing choice-set complexity, reducing preference uncertainty, focusing on goals rather than the means to achieve those goals, and adopting appropriate decision-making styles.

CHOICE OVERLOAD AND MODERATORS

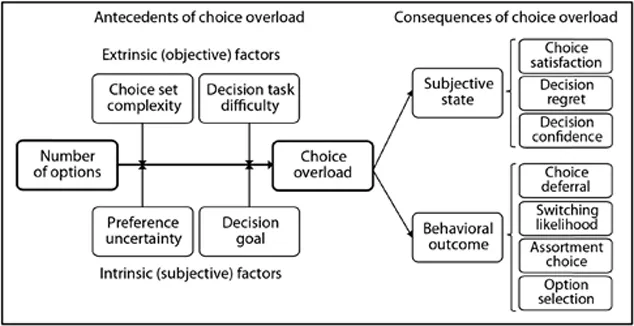

Moderators of CO include factors that explain when CO effects occur, increase, decrease, or are reversed. According to Chernev et al. (2015), CO research investigates causal relationships between the number of choices and subjective states (e.g., satisfaction, regret, confidence) or behavioral outcomes (e.g., making no choice, switching to another option, choosing small assortments, choosing utilitarian options). This literature stream challenges the conventional belief that “more is better” by providing empirical evidence that “less is more.”

Most people believe that having more choices is better than having just a few. Economists claim that having more choices maximizes utility because people can make better informed decisions (Benartzi & Thaler, 2001; Lancaster, 1990). This economic perspective is supported by other studies in psychology (e.g., Langer & Rodin, 1976); decision-making (e.g., Bown, Read, & Summers, 2003); consumer behavior (e.g., Greenleaf & Lehmann, 1995); and marketing (e.g., Anderson, Taylor, & Holloway, 1966). The retail industry also reaps the benefits of having large assortments (Broniarczyk, Hoyer, & McAlister, 1998; Kahn & Lehmann, 1991). Specifically, stores with larger assortments are perceived as more attractive (Oppewal & Koelemeijer, 2005), and achieve more sales (Kahn & Wansink, 2004; Koelemeijer & Oppewal, 1999) than stores with smaller assortments.

Paradoxically, a superfluity of choices restricts decision-making. Although large assortments may seem appealing, people also face a high level of uncertainty and difficulty when trying to select the optimal alternative. This argument is evidenced in Iyengar and Lepper’s (2000) experiments. They find that, when compared with people choosing from a small choice set (six options), people choosing chocolates from a large choice set (30 options) perceive that the task is not only more enjoyable but also more difficult and frustrating. Unexpectedly, the authors also find that people in the large choice set are less likely to purchase and are less satisfied with their choice than people in the small choice set. Iyengar and Lepper’s (2000) seminal paper has heated up the debate on CO and attracted more attention from researchers in different fields and disciplines.

While empirical evidence of the CO phenomenon has been reported widely, previous studies fail to come to a cohesive understanding as to whether and when CO effects arise (Chernev et al., 2015). To resolve the paradox of having many choices, Scheibehenne et al. (2010) and Chernev et al. (2015) conduct separate meta-analyses to investigate whether the CO phenomenon is robust. On the one hand, Scheibehenne et al. (2010) claim that the CO phenomenon does not exist, and no sufficient boundary condition has been found in which CO effects reliably occur. On the other hand, Chernev et al. (2015) argue that the negative effect of assortment size on CO is significant, even after the influences of boundary conditions are accounted for. Chernev et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis also addresses Scheibehenne et al.’s (2010) limitations by having a larger data set and conceptually deriving moderating factors before the analysis is run (instead of simply reporting moderators from individual studies).

The CO literature also provides some plausible explanations as to why people feel overwhelmed when choosing from a large range of items. It is arguable that CO effects occur as a result of comparisons between diminished benefits versus increasing costs when the assortment size increases (Chernev & Hamilton, 2009; Kaplan & Reed, 2013; Reutskaja & Hogarth, 2009). The extensive cognitive effort required to evaluate options (Fasolo, Carmeci, & Misuraca, 2009; Sela, Berger, & Liu, 2009) or increasing anticipated regret and counterfactual thinking (Carmon, Wertenbroch, & Zeelenberg, 2003; Fasolo, McClelland, & Todd, 2007; Goodman, Broniarczyk, Griffin, & McAlister, 2013; Gourville & Soman, 2005; Gu, Botti, & Faro, 2013; Sagi & Friedland, 2007) can also explain why people are less content with alternatives chosen from large assortments. In addition, people may be less satisfied with their choice because their high expectations for the alternative chosen from large, rather than small, assortments are disconfirmed (Diehl & Poynor, 2010). Nevertheless, the CO literature has not reached a comprehensive understanding as to under which conditions these underlying processes occur.

Recently, CO research has shifted from presenting empirical evidence of CO effects to finding certain boundary conditions as to when CO reliably happens or is alleviated (Chernev, Böckenholt, & Goodman, 2010). Chernev et al. (2015) integrate previous studies by categorizing CO moderators into two broad types: (1) extrinsic moderators, which relate to a choice problem and are applied to all individuals, and (2) intrinsic moderators, which reflect personal knowledge and motivations when dealing with the choice problem (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Conceptual Model of the Impact of Assortment Size on Choice Overload (Chernev et al., 2015).

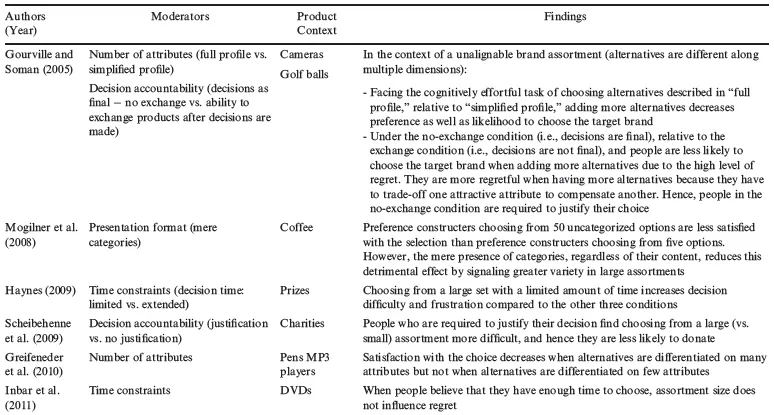

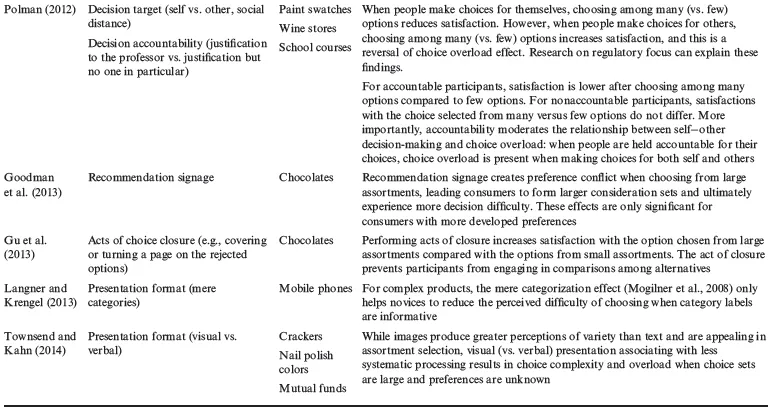

Chernev et al. (2015) further divide extrinsic moderators into two groups: decision task difficulty and choice-set complexity. Decision task difficulty moderators affect characteristics of the whole decision-making problem but do not influence values of particular options in the choice set (Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). In this group, Chernev et al. (2015) find four moderators: time constraints (Haynes, 2009; Inbar, Botti, & Hanko, 2011); decision accountability (i.e., requiring consumers to justify their decisions, Gourville & Soman, 2005; Scheibehenne, Greifeneder, & Todd, 2009); number of attributes describing each option (Gourville & Soman, 2005; Greifeneder, Scheibehenne, & Kleber, 2010); and presentation format (Townsend & Kahn, 2014). This chapter adds three additional moderators: acts of choice closure (i.e., signaling that the choice has been completed, Gu et al., 2013); recommendation signage (Goodman et al., 2013); and decision target (Polman, 2012). Furthermore, this chapter finds further empirical evidence for presentation format (Langner & Krengel, 2013; Mogilner, Rudnick, & Iyengar, 2008). The effects of decision task difficulty moderators are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Moderators of Assortment Size Effect – Decision Task Difficulty.

Unlike decision task difficulty moderators, choice-set complexity moderators affect values of particular options in the available choice set (Payne et al., 1993). These moderators include the presence of a dominant option (Sela et al., 2009), the options’ overall attractiveness (Chernev & Hamilton, 2009), the options’ alignability (Gourville & Soman, 2005), and the complementarity of options (Chernev, 2005). This chap...