eBook - ePub

Work-Integrated Learning in the 21st Century

Global Perspectives on the Future

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Work-Integrated Learning in the 21st Century

Global Perspectives on the Future

About this book

Work-Integrated Learning in the 21st century: Global perspectives on the future, explores new questions about the state of work for new university and college graduates in the context of Work-Integrated Learning (WIL). As these 'Millennials' graduate, they are entering a precarious labour market that is filled with ambiguity and uncertainty, creating a great deal of anxiety for those trying to develop skills for highly competitive jobs or jobs that do not yet exist. In their pursuit of skill acquisition, many are participating in WIL programs (e.g., cooperative education, internships) which allow them to gain practical experience while pursuing their education. With a focus on WIL, this book examines issues involved in developing work ready graduates. Topics include mental health and well-being - an urgent matter on many campuses; remote working - an aspect of the information and social media age that is becoming more prevalent as the precarity of work increases; issues of diversity and discrimination; ethics and professionalism; global citizenship and competency; and the role that higher education institutions need to play to prepare students for the challenges of economic shifts. These topics are timely and relevant to the situations faced by new graduates and those who prepare them for the world beyond school. The chapters provide a close examination of the issues from a global perspective, particularly as experiential education and work-integrated learning programs are becoming more prevalent in higher education and viewed as essential for preparing millennials for the 21st century competitive labour market.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

LEARNING, WORK, AND EXPERIENCE: NEW CHALLENGES AND PROJECTIONS FOR WIL

TOWARD A MODEL OF WORK EXPERIENCE IN WORK-INTEGRATED LEARNING

ABSTRACT

Work experience is increasingly seen as an important complement to traditional higher education. There are a variety of forms of these educational programs, such as internships, sandwich programs, field work, and cooperative education, that are referred to generically as Work-Integrated Learning (WIL). As yet, however, there is relatively little research on the concept of work experience and considerable inconsistency in its definition and measurement. This chapter describes some of the research and writing from the industrial and organizational psychology field and its relevance to WIL. Based on the previous work, a model of work experience, specifically developed to aid our understanding of the role of work experience in WIL, is proposed. Three dimensions are suggested: level of specificity (task, job, organization, and career), measurement mode (number, time, relation to program, density, timing, and type), and version of WIL (cooperative education, sandwich, etc.). The model also includes individual factors and contextual factors as influences on work experience. Both immediate and secondary outcomes are described. Finally, the applicability of the model to several examples of WIL research are discussed and suggestions for future research are offered.

Keywords: Work experience; WIL; factors affecting work experience; outcomes of work experience

INTRODUCTION

The inclusion of a period of practical work related to the academic curriculum in postsecondary (tertiary – i.e., university, college) education has a long history, dating back to more than 100 years in both Britain and the United States. There are many forms of this type of educational program, including cooperative education, internships, and research assistantships (Groenewald, Drysdale, Chiupka, & Johnston, 2011), as well as many names associated with these programs (see Gardner & Bartkus, 2014 for a list). Increasingly, however, the term work-integrated learning (WIL) has come to be accepted as “an umbrella term used for a range of approaches and strategies that integrate theory with the practice of work within a purposefully designed curriculum” (Patrick et al., 2008, p. iv).

The one characteristic common to all WIL programs, be they cooperative education programs, internships, sandwich placements, practica, or field work, is the acquisition of work experience. Work experience is deemed to be so significant by recruiters that it is frequently listed as a prerequisite to be considered for a job, and in times of high unemployment, when many applicants are competing for every vacancy, it may be used as the initial step in the screening process (Catano, Wiesner, Hackett, & Methot, 2010). As a result, there has been a substantial increase in the number of students taking internships, both paid and to a greater extent, unpaid in the last 25 years (Gardner, 2011). Knowing the importance of gaining experience, business and industry representatives (Business Council of Canada, 2016) and government advisers (Government of Ontario, 2016) are now calling for mandatory WIL programs at both secondary (high school) and postsecondary levels. Given this, it is reasonable to ask what the meaning of the term work experience is and what characteristics are necessary for work experience to have an effect. To date, there has been very little research on work experience per se, or on the necessary or desirable conditions for work experience to have an effect. This chapter will review the literature on work experience, examine the characteristics of work experience that may have an effect on the young person participating in a WIL program, and propose a model of work experience explicitly for WIL programs. However, before defining and examining the characteristics of work experience, it is necessary to define work itself.

While the Oxford Dictionary (n.d.) defines work as activity “involving mental or physical effort done in order to achieve a result,” industrial psychologists traditionally define work as activity that produces goods or services valued by others, for which one is paid, is carried out according to a time schedule, and is supervised by others. Increasingly, however, unpaid or volunteer work is included, and in this technological era, has become 24 × 7 and not restricted to a time schedule. Furthermore, entrepreneurial and consulting work is normally carried out alone or with a group of collaborators and without a supervisor, also demonstrating that the traditional definition is obsolete. Given this change in thinking about work, any activity that produces goods or services (of value to the community at large), whether the work is paid or not, on a strict time schedule, or supervised by others, will be treated as work in this chapter. (For a discussion of the many meanings of work, see Hulin, 2014, pp. 10–15.)

“Work is the primary activity of lives” (Hulin, 2014, p. 15). In addition to usually providing us with an income, it provides structure to our lives, social relationships, and a purpose to life. We identify with our work and are known by what we do (i.e., even in retirement I say that I am a psychologist). Work provides us with feelings of self-worth and self-esteem (Hulin, 2002). One has only to examine the negative effects of unemployment (Wanberg, 2012) or problems in retirement (Conroy, Franklin, & O’Leary-Kelly, 2012) to appreciate how important work is to the individual. Not surprisingly, therefore, many university and college students are concerned about their employment prospects upon graduation (Drysdale & McBeath, 2014), and as mentioned above, the importance of having some work experience in order to be employable.

WORK EXPERIENCE DEFINED

Work experience is one of the most important concepts in human resource research and practice, yet there remains inconsistency in its definition and meaning (see, e.g., Hofmann, Jacobs, & Gerras, 1992; Rowe, 1988). Since those early articles there have been other attempts to delineate work experience, but the most important paper on this issue is by Quinones, Ford, and Teachout (1995), who state that work experience refers to “events that are experienced by an individual that relate to the performance of some job” (p. 889).

A first step in looking for aspects of jobs that might be of relevance to WIL is to consider the various expectations of our stakeholders – primarily students, employers, and postsecondary institutions. For the students, the strongest motivation for entering a WIL program is to gain experience that will enhance their chances of finding employment upon graduation. That need is clearly being met, as has been shown from the earliest study of cooperative education (Wilson & Lyons, 1961) to the more recent and extensive research with Ontario students participating in a variety of WIL programs at the postsecondary level (Sattler & Peters, 2013). In an earlier study, Sattler and Peters (2012) also report that most employers (the second stakeholder group) state that their primary interest in participating in cooperative or work-integrated education is in attracting and recruiting future employees. In fact, over half of the WIL employers who participated in the 2012 Sattler and Peters study hired a WIL graduate for a permanent position. Finally, the third stakeholder to consider is the institution: faculty members see the highest benefits of WIL as labor market advantages for students, but also see benefits to the institution in terms of strengthening links to the business community (DeClou, Sattler, & Peters, 2013). It is important to note that all three stakeholders hold expectations about, and see the benefits of, WIL programs that are centered on improving the employability of students and enhancing their career development. This focus on work makes clear the necessity of research paying more attention to the work experience in WIL programs and the jobs students hold.

As mentioned earlier, a paper by Quinones et al. (1995) made a significant contribution to our understanding of the meaning and measurement of work experience; they conceptualized work experience as having two dimensions: level of specificity and measurement mode. Three levels of specificity were suggested: task, job, and organization; and three levels of measurement mode: amount or number, time, and type. Crossing these two dimensions to form a matrix results in nine cells – such as time on the job, type of organization, or number of times a task is performed. Each of these cells represents a measure of work experience at one of the three levels of specificity.

Because job performance is of special interest in human resource research, Quinones et al. (1995) examined its relationship to the various aspects of work experience in the cells of the matrix (e.g., number of organizations, etc.). Both a literature review and a meta-analysis were conducted. The literature review revealed that the most frequent measure of experience was time, followed by amount or number, and finally type of experience. The majority of studies measured work experience at the job level, followed by the organizational level, and the task level. Meta-analysis of the data from the studies in the literature review revealed a corrected correlation of 0.27 between work experience and job performance, indicating that there is a positive relationship between the two variables. This relationship, however, was moderated or affected by measurement mode, level of specificity, and type of criteria for the assessment of job performance. Further analysis showed that the correlation between experience and performance reached 0.43 if amount or number was the measure used, and 0.41 if task was measured. In other words, for experience to have a sizable effect on performance, one should measure the amount of experience, not time as is customary on resumes, and measure the experience on tasks, not in a job as is usually done. Moreover, correlations were higher when job performance was assessed with “hard” (e.g., number of items produced or sales) than with “soft” criteria (e.g., supervisor ratings). These results led to the conclusion that “various measures of work experience capture different aspects of job-relevant experience” (p. 904). A later chapter by Quinones (2004) examined some of the literature since the original article, but maintains the two-dimension, nine-cell model.

Using the groundwork provided by Quinones et al. (1995), Tesluk and Jacobs (1998) further developed the construct of work experience. They proposed two additional levels of specificity – work groups and occupation; and two interactive measures to measurement mode. The interactive measures were density, or the intensity of the experience, and timing, or when the experience occurred relative to the level of learning or achievement of the individual. Their model also incorporates contextual factors, such as the work environment or the larger social environment, and individual factors, such as ability and motivation. Both contextual and individual factors not only affect work experience directly, but they also affect what is learned from the work experience. Finally, Tesluk and Jacobs proposed both immediate outcomes (knowledge and skills, work motivation, and work-related attitudes) and secondary outcomes (job performance and career development).

Since these two important articles by Quinones et al. (1995) and Tesluk and Jacobs (1998), several studies, primarily dealing with leadership or management development, have examined aspects of the relationship between experience and performance. For example, Dragoni, Oh, Vankatwyck, and Tesluk (2011) found that accumulated work experience and an individual factor – cognitive ability – were the strongest predictors of executives strategic thinking, and extraversion was related to the amount of work experience acquired. Another interesting study is that by Carette, Anseel, and Lievens (2013) in which challenging assignments were found to have a beneficial effect in the early career but not in the mid-career of managers, a confirmation of the importance of the timing measurement mode.

A MODEL OF WORK EXPERIENCE FOR WORK-INTEGRATED LEARNING

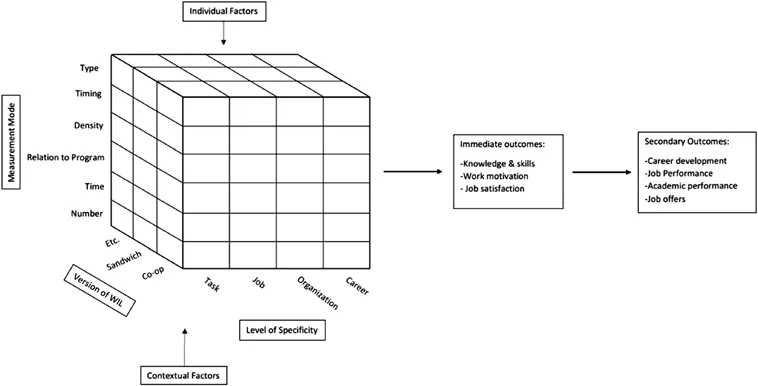

The Tesluk and Jacobs (1998) model provides a good starting point for developing a model of work experience explicitly designed for WIL. First, work experience in the context of WIL is multidimensional; that is, it has numerous aspects, is affected by a number of factors, and has several outcomes. The WIL model described here (see Fig. 1, adapted from Quinones et al., 1995 and Tesluk and Jacobs, 1998) includes some of the work experience characteristics found in their articles, but adds a new dimension and a few factors especially relevant to WIL, and excludes a number that are more relevant to permanent positions.

Fig. 1. Model of Work Experience for Work-Integrated Learning.

Levels of specificity in this model are task, job, and organization (taken from Quinones et al., 1995) and career (called occupation by Tesluk & Jacobs, 1998) is added. Measurement mode has amount (renamed number), time, and type, as proposed by Quinones et al., and density and timing added by Tesluk and Jacobs, and adds relation to academic program. This produces a 4 × 6 matrix, with 24 cells, though not all cells may be important in WIL. A third dimension – the form of WIL (co-op, internship, etc.) – is added, making as many multiples of 24 cells as there are forms of WIL. Obviously, in any one study only a selection of WIL programs, or only one, would be examined. Many individual factors may affect work experience, such as a student’s ability, personality factors, openness to experience, or motivation to achieve. Similarly, there are many contextual factors that may influence work experience in WIL, such as the supervisor, other staff members, the involvement of the coordinator or academic institution, and the work environment. Note that both individual and contextual factors are predicted to affect cells differentially; for example, the work supervisor might be expected to have a greater influence on the number and challenge of tasks than on any measures of organization or career. Similarly, motivation to achieve might influence time spent on the job, but not number of tasks.

Lastly are the outcomes of experience proposed by Tesluk and Jacobs (1998): immediate or primary ones and less immediate or secondary ones. The immediate outcomes include three of the group (knowledge, skills, abilities, and other attributes – often referred to in the industrial and organizational literature (e.g., Catano et al., 2010) as KSAOs. Note that ability, an individual factor, is not affected by work experience. The importance of these outcomes for the future employment and effective performance of students cannot be over-emphasized, as KSAOs are the basis for decisions on selection, training, and promotion in organizations (Catano et al., 2010). Less immediate, or secondary outcomes such as job performance and career development follow from the primary outcomes of work experience. Added in the WIL model is job satisfaction to the immediate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Part I Learning, Work, and Experience: New Challenges and Projections for Wil

- Part II Affordances, Impacts, and Challenges of New Technologies

- Part III Work-Readiness for a Diverse World Repositioning Work

- Part IV Health, Wellbeing, and Pathways to Success

- About the Authors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Work-Integrated Learning in the 21st Century by Tracey Bowen, Maureen Drysdale, Tracey Bowen,Maureen Drysdale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Carriera. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.