![]()

1. Don’t Know Much about Medicare?

Upon nearing age 65, John Pearson1 went to his local Social Security office to apply for his retirement benefits. He was planning to recoup the Social Security taxes he had been paying his entire working life, but he had no intention of enrolling in Medicare. After reading many articles about Medicare, John understood how bureaucratic the program could be. (There are more than 130,000 pages of Medicare regulations.)2

John believed that, over time, enrollment in Medicare would increasingly diminish his ability to choose medical practitioners and would limit his choice of treatments. Also, the thought of dealing with a huge government bureaucracy regarding personal health care decisions at the end of life seemed intolerable. Even though he had been paying taxes to support Medicare since its creation in the 1960s, he decided that when he retired he would forgo joining Medicare and instead continue paying premiums for the private, high-deductible, catastrophic health insurance plan he had purchased through a professional association.

However, John was astonished at what he discovered the day he applied for his Social Security retirement benefits. He informed the office clerk that he wanted to apply for retirement benefits. The clerk proceeded to ask him for personal identification information, such as his full name, Social Security number, date of birth, and other information. The clerk then printed out a ‘‘personalized’’ form titled ‘‘Application for Retirement Insurance Benefits.’’ That form included the following statement:

I apply for all insurance benefits for which I am eligible under Title II (Federal Old-Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance) and Part A of Title XVIII (Health Insurance for the Aged and Disabled) of the Social Security Act, as presently amended.

The clerk then asked John to sign the application form she had completed in order to further process his request for benefits. He paused because he knew that ‘‘Part A of Title XVIII’’ (in the above statement) really meant Medicare Part A (hospitalization coverage). He immediately informed the clerk that he did not intend to enroll in Medicare Part A. The clerk seemed surprised that he would want to reject it. In the end, she asked John four times, ‘‘Are you sure you don’t want to sign up for Medicare?’’ All told, John assured the clerk four times that he did not want to sign up for Medicare. He completed the application by drawing a line through the statement that would have him applying for Medicare Part A, initialing the strikeout of the offending statement, and signing the altered application form.

Finally, John asked the clerk for a copy of the signed application, which showed he had struck out and initialed the statement that he was applying for Medicare Part A. The clerk, with some hesitation, gave him a copy. He returned home assuming he was not going to be enrolled in Medicare Part A without his written, informed consent.

Some five weeks later, John was surprised when he received a Medicare card in the mail. The card stated, ‘‘This is your Medicare card. It shows if you have hospital insurance, medical insurance, or both. . . . Show your card when you receive health services.’’

John’s card showed that he had Medicare Part A. How could the government enroll him in the Medicare Part A program when he had explicitly declined enrollment? John later discovered that enrollment in Medicare Part A is mandatory if you want to receive Social Security benefits.

‘‘I felt deceived,’’ says John. ‘‘No one ever told me I would be forced to accept enrollment in Medicare in order to receive my Social Security retirement benefits.’’ Like most Americans, John knew he was paying taxes to support the program. But he didn’t know he would be forced to participate in Medicare Part A—the largest part of the Medicare program.

One might wonder why senior citizens, such as John, would want to reject ‘‘free’’ hospital insurance under Medicare Part A, especially since they’ve contributed payroll taxes to support the program for many years. Just as many parents forgo public education and instead choose to pay for private schooling (even though they’ve paid taxes and the public education is ‘‘freely’’ available to their children), seniors might choose to pay privately for their health insurance for a number of reasons. Consider, for example, that enrollment in Medicare automatically results in the following:

- The federal government dictates what types of services and treatments, including new life-saving technology, are ‘‘medically necessary’’ for seniors and what will be covered under Medicare.

- Medicare has the final say on hospital and doctor fees, and it requires providers to submit claims to the federal government. Those policies interfere with the doctor-patient relationship.

- Once enrolled in Medicare Part A (which happens automatically when one applies for Social Security benefits), the only way seniors can end their enrollment is by withdrawing from Social Security and repaying all cash benefits already paid to them.3

- The federal government effectively prohibits Medicare beneficiaries from paying privately for Medicare-covered services (most services).4 The only way physicians can accept private payment from Medicare beneficiaries (for Medicare-covered services) is if they do not accept Medicare reimbursement (for treating Medicare patients) for two years. Since few doctors have enough Medicare patients who are willing to pay all their medical bills without Medicare reimbursement, the federal government realistically prevents seniors from spending their own money on the health care of their choice.5 Yet, those under age 65 with employer-sponsored health insurance are free to pay privately (instead of having their insurers pay) for any medical care they choose.

These are just a few of the reasons seniors might choose to reject their entitlement to Medicare and instead pay privately for health insurance upon turning age 65.

These and many other startling facts about Medicare are not widely known among the general public. Here are some frequently asked questions about Medicare.

What Is Medicare?

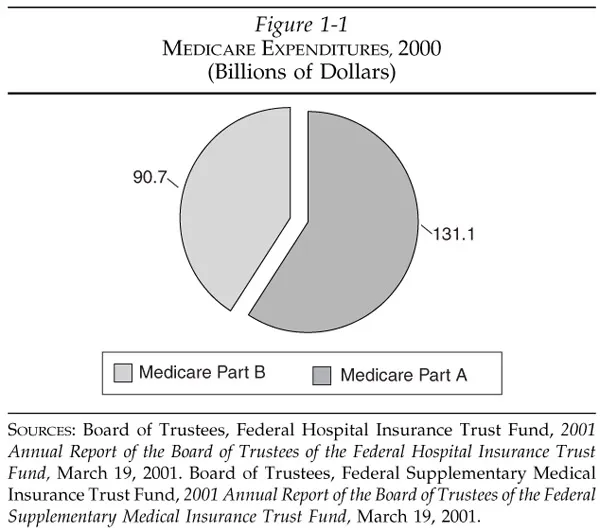

Medicare is the largest single payer for health care in the United States, representing 12 percent of federal spending.6 In 2000, it covered 39 million seniors and persons under 65 with certain disabilities.7 Total program costs amounted to $221.8 billion in 2000 (Figure 1-1) and are projected to more than double over the next decade—reaching $491 billion by 2011.8

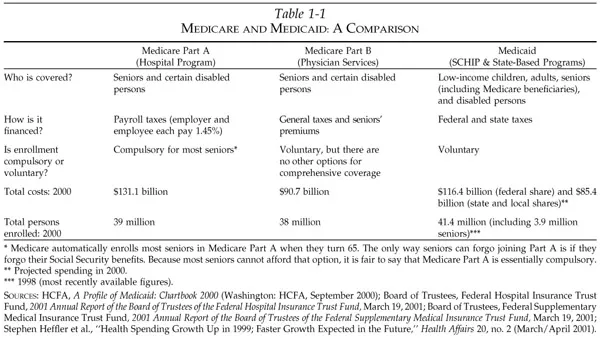

Medicare is administered by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), recently renamed the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) but hereafter referred to as HCFA, which contracts with insurance companies to process claims and pay medical bills. It is often confused with Medicaid, which is a government program for low-income children and adults. Both programs are administered by HCFA. But the major differences are that Medicare covers seniors and disabled persons regardless of their income, while Medicaid covers children, adults, and seniors who fall below a certain poverty level. Many seniors qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid—referred to as ‘‘dual eligibility.’’ Approximately 6 million persons are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid.9 Together, Medicare and Medicaid represent the largest payer of health care in the world.10

When people hear the term Medicare, the first thing they should do is stop and ask, ‘‘Which part are you referring to?’’ There are big differences between the various parts of the program.

What Does Medicare Cover and How Is It Financed?

Medicare is primarily divided into two major parts. Part A (Hospital Insurance or HI) covers limited amounts of inpatient hospital care, home care, hospice care, and care in a skilled nursing facility.11 Seniors are required to pay a deductible for each hospitalization (see Appendix A). This part of the program is financed by a 2.9 percent compulsory payroll tax.12 Workers and employers each contribute 1.45 percent of workers’ earnings. However, in reality the workers bear the full burden, because they ultimately receive lower wages when overall payroll taxes absorb a greater portion of their employers’ total labor costs.

Taxes for Medicare Part A appear on each worker’s earnings statement (W-2). That money, however, is not set aside for each worker’s own future health care costs. Rather, today’s Medicare payroll taxes are used for today’s beneficiaries. In 2000, workers paid over $144 billion into the Medicare Part A trust fund.13

Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance or SMI) pays for 80 percent (after seniors pay a $100 annual deductible) of approved doctor visits and other services not covered under Part A, such as ambulance services, outpatient hospital care, and X-rays (see Appendix B). It also covers some home care services and supplies. The majority of Part B spending—about 73 percent—is financed through general tax revenues. Another 23 percent comes from premiums paid by seniors, and the remaining 4 percent is financed by interest and other miscellaneous income. In 2000, taxpayers financed more than $65.9 billion toward doctor visits and outpatient medical services under Part B, and seniors contributed another $20.6 billion toward that part of Medicare.14

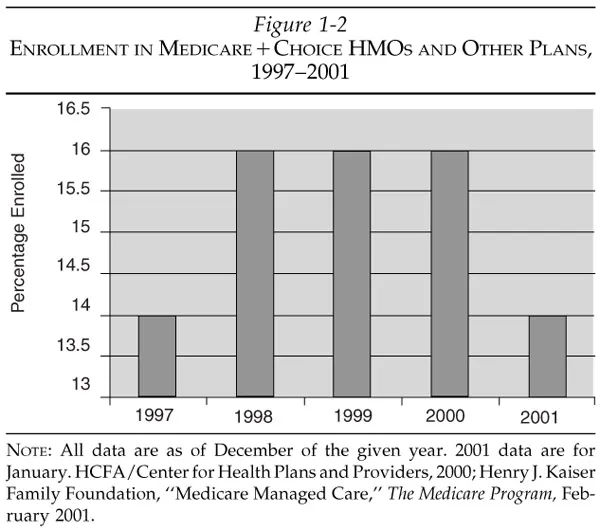

In addition, a Medicare Part C program, called MedicareםChoice, was established under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. It was created to provide more choices and encourage seniors to enroll in private plans. Medicare beneficiaries were supposed to be offered choices among the following types of health plans: traditional feefor-service (FFS) Medicare, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), medical savings accounts (MSAs), preferred provider organizations (PPOs), or newly created provider sponsored organizations (PSOs).15 The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the Medicare Part C program would lead to significant enrollments in private plans. It estimated that enrollment would grow from 14 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries in 1997 to 25 percent by 2002.

However, according to Robert Waller, M.D., chairman of the Healthcare Leadership Council, burdensome government regulations encouraged private companies to withdraw from the MedicareםChoice program. In February 2000, Dr. Waller told the Senate Finance Committee, ‘‘At first it seemed that plans were very willing to give MedicareםChoice a try. Forty new plans signed up in the first year following passage. But plans began withdrawing once they had begun to decipher the massive MedicareםChoice regulation published in 1998. . . . Now only 262 plans are signed up with MedicareםChoice, down from a high of 346 at the end of 1998.’’16 As of January 2001, 14 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in MedicareםChoice programs and only 174 plans were participating in Medicare—approximately half the number participating in 1998 (Figure 1-2).17

Moreover, while appearing to give seniors unbiased choices, MedicareםChoice severely restricts the MSA option. That is because the new program limited the number of beneficiaries who can choose MSAs to only 390,000 out of 39 million enrollees.18 Thus, only 1 percent of enrollees can choose an MSA, whereas all seniors can choose a managed care plan when it is available in their region.19 No medical savings account plans have been approved for seniors. HCFA has entered into only one contract for a PSO, and only one private fee-for-service plan has been approved.20 ‘‘While the aim of MedicareםChoice (MםC) was to expand choice, the choices available to Medicare beneficiaries have diminished since its inception,’’ notes Marcia Gold, senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research.21

The Part C program clearly maintains the government’s position as purchaser and contractor of seniors’ medical care. HCFA—not seniors—is the party who signs contracts with health plans and providers under all parts of Medicare (Parts A, B, and C). (See Table 1-1 for a comparison of Medicare Parts A and B and Medicaid.) In reality, the only plans seniors can choose from under the Medicare program are the ones HCFA decides to contract with and, conversely, those plans that agree to do business with the federal government. So the name ‘‘MedicareםChoice’’ is just that, only a name. It does not offer individuals true freedom of choice.

Does Medicare Provide Catastrophic Coverage?

As a citizen taxed to support the nearly $222-billion-a-year Medicare program, you probably assume that once you reach 65, it will provide you catastrophic coverage. It doesn’t. Medicare doesn’t pay for hospitalizations beyond 150 days, even though such hospitalizations would be considered truly catastrophic.22 There is no cap on the amount of out-of-pocket costs that beneficiaries must pay. Medicare currently requires seniors to pay $792 for the first 60 days of each hospitalization, $198 per day for days 61–90, and $396 per day for days 91–150.23 This is the opposite of sound insurance principles. Medicare should pay more—not less—when seniors face catastrophic illnesses. Because Medicare’s hospital coverage is limited, many seniors buy ‘‘Medigap’’ insurance to make sure they don’t get stuck with huge medical bills.24

Medicare also generally doesn’t cover long-term care expenses, such as nursing home care, unless seniors have been hospitalized.25 For example, seniors cannot use the money they have contributed toward Medicare to pay for a nurse’s aide to assist with bathing unless the service is connected to a hospitalization.

From its inception Medicare did not—and still does not—pay for many types of routine services. For example, it doesn’t cover dental care, routine eye examinations, most prescription drugs, most nursing home care, and routine physical examinations. Medicare also doesn’t cover many types of alternative medicine that are in great demand today, including acupuncture, homeopathy, and naturopathy. It covers only a limited amount of chiropractic care. (Appendices A, B, and C list covered and noncovered services.)

Do Taxpayers Have a Right to Their Medicare Contributions?

Most people assume that citizens are paying into the Medicare program and that the federal government will repay them benefits at some future date. However, it is important to stress that taxpayers don’t have a binding contract with the U.S. government for future Medicare benefits.

The program was enacted as part of the Social Security Act Amendments of 1965, and the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that Social Security is not a contributory insurance system because Social Security taxes are paid into the general treasury.26 The trust fund is merely an accounting mechanism.

Individuals do not have a legally binding contractual right to their Social Security benefits.27 The same is true for Medicare. It is a payas-you-go transfer program whereby the government collects money from today’s taxpayers and uses it to pay part of today’s seniors’ medical bills. Congress and the President can change, add, or eliminate Medicare benefits at any time.

Does Medicare Pay Cash or Medical Benefits?

Medicare differs from the true insura...