This is a test

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In Crisis of Abundance: Rethinking How We Pay for Health Care, economist Arnold Kling argues that the way we finance health care matches neither the needs of patients nor the way medicine is practiced. The availability of "premium medicine," combined with patients who are insulated from costs, means Americans are not getting maximum value per dollar spent. Using basic economic concepts, Kling demonstrates that a greater reliance on private saving and market innovation would eliminate waste, contain health care costs and improve the quality of care. Kling proposes gradually shifting responsibility for health care for the elderly away from taxpayers and back to the individual.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Crisis of Abundance by Arnold Kling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. The Rise of Premium Medicine

Here are five key points to consider:

• Over the past 30 years in the United States, the practice of medicine has become more expensive. Compared with the past, today’s medical care might be termed “premium medicine.”

• Premium medicine utilizes both more physical capital (such as MRI machines) and human capital (specialists).

• Premium medicine reflects cultural expectations that call for a high level of effort to diagnose ailments correctly and treat them effectively.

• Premium medicine clearly has increased the cost of health care. The evidence on whether it has increased the benefits of health care is mixed.

• Because we have conquered many infectious diseases, to increase longevity further we must tackle degenerative diseases, the treatment of which brings less bang for the buck in terms of life extension. This will reinforce the trend toward more visible cost increases and less visible benefit increases.

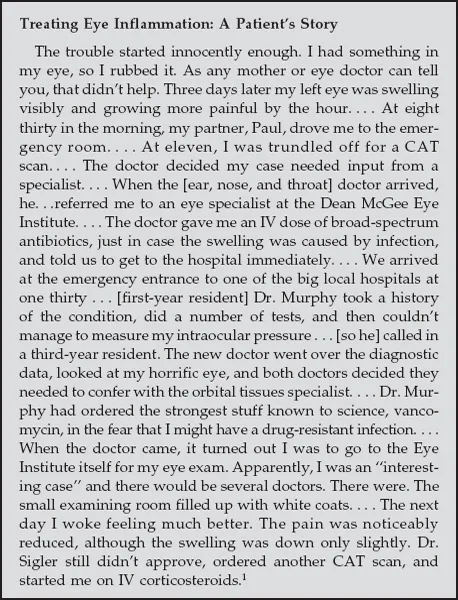

On April 11, 2005, a Weblogger writing under the pseudonym Quixote published a long, dramatic account of her experience of obtaining treatment for an inflammation around her eye. She vividly described her ensuing odyssey, from the opening trip to an emergency room through her frustration with her expenses and with private health insurance. Her story seems to touch on every aspect of our health care system, from hospital food to emergency services. The sidebar excerpts only those parts that deal with actual attempts to diagnose and treat her ailment.

My guess is that 30 years ago, a patient with similar symptoms would have been treated “empirically,” a term doctors use to describe a situation for which they do not have a precise diagnosis and treatment, so that instead they must use guesswork. A layman’s synonym for treated empirically would be “trial and error.” In this case, the patient might have been sent home with an antibiotic and perhaps a prescription for Prednisone, a steroid used to reduce inflammation. There would have been nothing else to do. In 1975, computerized medical imaging technology was new and exotic, with limited applications.

In contrast, in 2005, over the course of a few days Quixote was given a computed tomography (CT) scan, referred to a specialist, sent to a different hospital, referred to a specialty clinic, seen by a battery of specialists there, and given yet another CT scan. Ultimately, however, she was sent home, as she might have been 30 years ago, with an antibiotic, Prednisone, and no firm diagnosis.

Compared with 30 years ago, Quixote received more services, in the form of specialist consultations and high-tech diagnostics. However, the ultimate treatment and outcome were no different.

This does not mean that medicine is no better today than it was a generation ago. The CT scans and specialist consultations could have turned out differently. They might have been critically important, depending on her actual condition. Under some circumstances, treating Quixote empirically with an antibiotic and Prednisone could have been a mistake, perhaps costing some or all of her sight in one eye.

Such is modern medicine in the United States. Doctors are able to take extra precautions. They can use more specialized knowledge and better technology to try to pin down the diagnosis. They can perform tests to rule out improbable but dangerous conditions. But only in a minority of cases does the outcome deviate from what would have been the case 30 years ago.

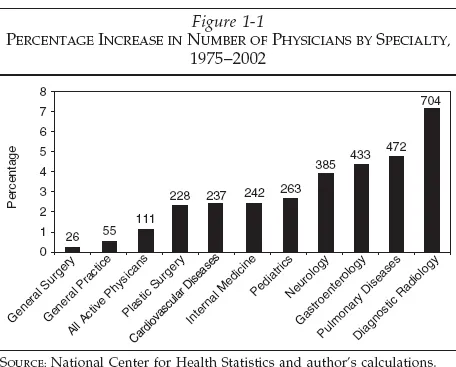

Figure 1-1 shows the growth in specialized medicine from 1975 to 2002. Over this period, the total population of the United States rose by 35 percent. Meanwhile, the total number of active physicians more than doubled, even though the number of general practitioners only increased by 55 percent, slightly more than the rate of increase in the population.2

The United States has perhaps the highest ratio of specialists to general practitioners in the industrial world. However, in aggregate data, it is very difficult to find a significant effect of specialist supply on health care outcomes.3

The United States also tends to be an outlier in its use of expensive medical procedures. Heart bypass surgery is about three times as prevalent here as in France and about twice as prevalent as in the U.K. Angioplasty is more than twice as prevalent here as in France and about seven times as prevalent as in the U.K.4

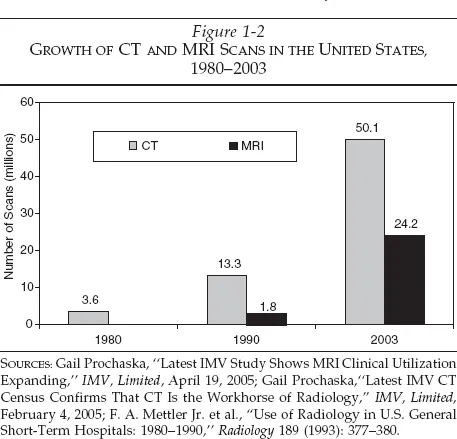

Specialization represents the human capital component of premium medicine. The other component is physical capital, particularly diagnostic imaging technology. Todd A. Gould points out that “As late as 1982, there were but a handful of MRI scanners in the entire United States. Today there are thousands. We can image in seconds what used to take hours.”5

According to the marketing consulting firm IMV, more than 24 million MRI exams were conducted in 2003, and more than 50 million CT scans were performed in the same year.6 Each represents a 10 percent increase from 2002. Combining this information with data from radiology researcher Dr. Fred A. Mettler and colleagues provides the following graph for the growth of high-tech diagnostic imaging in the United States (see Figure 1-2).7

In March 2005, Mark Miller, Executive Director of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, testified that “Diagnostic imaging services paid under Medicare’s physician fee schedule grew more rapidly than any other type of physician service between 1999 and 2003. While the sum of all physician services grew 22 percent in those years, imaging services grew twice as fast, by 45 percent.”8 More detailed breakdowns showed that “Spending for MRI, CT, and nuclear medicine has grown faster than for other imaging services. Thus, these categories represent an increasing share of total imaging spending. MRI spending grew by 116 percent between 1999 and 2003, nuclear medicine by 104 percent, and CT by 84 percent.”9 Miller’s testimony noted that there is wide variation in the usage rate of diagnostic imaging service across regions, but it is difficult to find a relationship between health outcomes and usage rates.

American Cultural Expectations

The term “premium medicine” is meant to describe this heavy usage of specialist consultations and advanced medical technology. I believe that it embodies American cultural considerations, including ur can-do spirit, our high expectations as health care consumers, and the high standards to which doctors hold themselves.

The cliche of 30 years ago was “Take two aspirin and call me in the morning.” Today, the wait-and-see approach is going the way of the house call. Instead, premium medicine looks for ways to determine the causes of ailments, bring immediate relief, and eliminate risks.

An important characteristic of premium medicine is that many procedures have a low probability of affecting the outcome. In fact, often the procedures do not even affect the treatment plan.

Consider three options for treatment:

• Do nothing.

• Treat empirically.

• Treat on the basis of a thorough diagnosis, ruling out minor possibilities.

The first option is what was meant by “take two aspirin and call me in the morning.” in fact, ailments often get better if they run their course. At the other end of the scale, a terminal ailment’s progress may be such that no treatment can avert the outcome. The intermediate cases are ones in which treatment might make a difference.

The second option is one a general practitioner follows on the basis of instinct and experience. Having seen similar cases before, the doctor proposes the treatment plan based on what worked in the past and the patient’s characteristics.

The third option incorporates premium medicine. Biomedical tests, diagnostic imaging, and specialist consultations are included in the process of determining a treatment plan.

Consider a sample of 1,000 patients who have a severe cough that seems to be a bronchial infection. If the option chosen is “do nothing,” suppose that 800 will get better and 200 will develop severe infections. If the option chosen is to “treat empirically” with an antibiotic, suppose that 998 will get better and only two patients will fail to recover. If the option chosen is to obtain a chest X-ray, suppose that all 1,000 patients will be given the correct treatment.

In this hypothetical example, the chest X-ray represents premium medicine. It would raise the cost for each of the 1,000 patients. However, the chest X-ray would change the course of treatment for only two of those 1,000 patients. Thus, the probability that premium medicine will affect the outcome in our example is only .002, or two-tenths of 1 percent.

Thus, although the costs are widespread and visible, the benefits are concentrated and hard to spot when diluted by the entire population. In particular, the benefits are unlikely to show up in aggregate statistics on health care, such as national average longevity.

Abundance and Premium Medicine

Premium medicine includes

• Routine screening procedures such as colonoscopies for people over age 50 or with a family history of colon cancer.

• MRIs and CT scans that are performed for the purpose of ruling out unlikely causes of symptoms (e.g., an MRI for someone complaining of lower back pain).

• “Heroic” efforts at late-stage treatment that usually fail but occasionally succeed.

The conditions that have given rise to premium medicine include

• Abundant medical resources, particularly the availability of specialists and advanced medical technology.

• High expectations on the part of patients.

• Strong desire on the part of doctors to meet impossibly high expectations.

• Fear of the consequences of not following premium procedures, in part because of malpractice litigation.10

• The belief that for patients with insurance, no consideration needs to be given to cost.

In short, there is a cultural component to premium medicine. Resource availability, high expectations, and third-party payments all provide support for premium medicine.

If premium medicine is the main reason that U.S. health care spending is higher than that of other countries, then an attempt to restrain health care spending by copying other countries' government-paid health care systems could backfire. For example, suppose that we treat as given our cultural attitudes toward medical care, with our bias toward taking extra precautions and undertaking more procedures whenever patients are not paying out-of-pocket. If we then layer onto this culture a system of government financing for all health care, spending would only increase beyond what we observe today.

One of the characteristics of premium medicine is that there is considerable regional variation in medical procedures, even controlling for patient characteristics. This variation has been found among the Medicare population, which is yet another indication that habits and culture are important determinants of (over-)utilization of medical services.

instead of government financing, the crisis of abundance may require a different policy prescription. If premium medicine is to be socially beneficial, then doctors and patients must be highly cognizant of costs and benefits. Government may promote research and education concerning probabilities and outcomes from various procedures. Financial reforms, however, should move more in the direction of providing patients the incentives to use medical care wisely, rather than in the direction of further insulating patients from costs.

Evidence for the Prevalence of Premium Medicine

According to a report on trends in health care utilization in the United States, in 2000 the number of office visits to specialists per 1,000 in the population was more than 1,400—very close to the number of office visits to primary care physicians (general practitioners, internists, and pediatricians).11 This occurred despite the fact that part of the focus of managed care in the 1990s was on reducing the utilization of specialists relative to primary care physicians.

The work of John Wennberg, Elliot Fisher, and Jonathan Skinner seems to confirm the prevalence of premium medicine.2 They found large variations across hospital referral regions (e.g., Minneapolis vs. Miami) in the amount of Medicare expenditures in the last six months of life, with no visible variation in survival rates. Dartmouth professor John Wennberg summarized research on variation in medical care in a lecture.13 Wennberg emphasized the importance of what he termed “preference-sensitive” care and “supply-sensitive” care.

Discussions of health care polic...

Table of contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. The Rise of Premium Medicine

- 2. Three Health Care Narratives

- 3. Dollars and Decisions

- 4. No Perfect Health Care System

- 5. Insulation vs. Insurance

- 6. Matching Funding Systems to Needs

- 7. Markets and Evolution

- 8. Policy Ideas

- Conclusion

- Notes

- About the Author