![]()

1. A Discovery in India . . .

What Everyone Knows

My first real job was as a mathematics teacher in Africa. Right out of college, a couple of years after Zimbabwe’s independence from Britain in 1980, I went to help “Comrade” Robert Mugabe build his new socialist society. And what better way to assist than through public education?

During my interview with the minister of education at the Zimbabwe High Commission in London, I asked to be assigned to a rural school so that I could really help the poor. He smiled, clearly understanding my motivation, I thought. To my chagrin, I found myself posted to Queen Elizabeth High School, an all-girls school right in the center of Harare, the capital. Queen Elizabeth had originally been a whites-only elite institution, although when I joined it had a mixture of races (“African,” “Asian,” and “European,” as they were classified).

“This government wouldn’t waste you in the rural areas!” the (white) headmistress laughed when I arrived, meaning to compliment me on my mathematics degree. She explained that many daughters of politicians from the ruling party, Zanu-PF, were enrolled in her school, and of course they would look after themselves first! I dismissed her cynicism, putting it down to racism, and the incongruence of my assignment to administrative error. I also found my niche in the school; it seemed all the children trusted me, so I was able to help them get along with one another. But I spent as much of my spare time as possible in the rural “communal lands,” experiencing the realities of life there firsthand. In the process, I developed links between an impoverished rural public school and my own, bringing my privileged urban pupils there to help them appreciate all that Mugabe was doing for the povo—the ordinary people.

Two years later, I managed to engineer an assignment to a public school in the Eastern Highlands. I lived and worked in a small school set on a plateau beneath the breathtakingly beautiful Manyau Mountains, from where the calls of baboons echoed as dusk fell and women returned from the river carrying buckets of water on their heads; leopards apparently still hunted at night on the rugged mountain slopes. I defended Mugabe’s regime to its critics, for at least it was engaged in bringing education to the masses, benefiting them in ways denied before independence. Before long, once richer urban people properly paid all their taxes and the international community coughed up a decent amount of aid, it would be able to make education free for all. That would be truly cause for celebration.

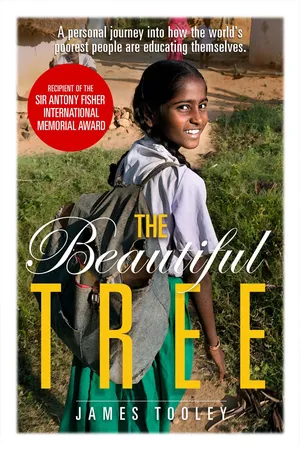

After all, everyone knows that the world’s poor desperately need help if every child is to be educated. Help must come from their governments, which must spend billions of dollars more on building and equipping public schools, and training and supporting public school teachers, so that all children can receive a free primary school education. But governments in developing countries cannot succeed on their own. Everyone knows that they, too, need help. Only when rich Western governments spend much more on aid can every child be saved from ignorance and illiteracy. That’s the message we hear every day, from the international aid agencies and our governments, and from pop stars and other celebrities.

As a young man, I believed this accepted wisdom. But over the past few years, I’ve been on a journey that has made me doubt everything about it. It’s a journey that started in the slums of Hyderabad, India, and has taken me to battle-scarred townships in Somaliland; to shantytowns built on stilts above the Lagos lagoons in Nigeria; to India again, to slums and villages across the country; to fishing villages the length of the Ghanaian shoreline; to the tin-and-cardboard huts of Africa’s largest slums in Kenya; to remote rural villages in the poorest provinces of northwestern China; and back to Zimbabwe, to its soon-to-be-bulldozed shantytowns. It’s a journey that has opened my eyes.

Read the development literature, hear the speeches of our politicians, listen to our pop stars and actors, and above all the poor come across as helpless. Helplessly, patiently, they must wait until governments and international agencies acting on their behalf provide them with a decent education. So we need to give more! It’s urgent! Action, not words! It’s all I believed during my early years in Zimbabwe. But my journey has made me suspect that it was, however well intentioned, missing something crucial. Missing from the accepted wisdom is any sense of what the poor can do—are already doing—for themselves. It’s a journey that changed my life.

Something quite remarkable is happening in developing countries today that turns the accepted wisdom on its head. I first discovered this for myself in January 2000.

In the Slums of Hyderabad, a Discovery . . .

After a stint teaching philosophy of education at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, I returned to England to complete my doctorate and later became a professor of education. Thanks to my experiences in sub-Saharan Africa and my modest but respectable academic reputation, I was offered a commission by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation to study private schools in a dozen developing countries.

The lure of faraway places was too enticing to resist, but I was troubled by the project itself. Although I was to study private schools in developing countries, those schools were serving the middle classes and the elite. Despite my lifelong desire to help the poor, I’d somehow wound up researching bastions of privilege.

The first leg of the trip began in New York in January 2000. As if to reinforce my misgivings that the project would do little for the poor, I was flown first class to London in the inordinate luxury of the Concorde. Forty minutes into the flight, as we cruised at twice the speed of sound and two miles above conventional air traffic, caviar and champagne were served. The boxer Mike Tyson (sitting at the front with a towel over his head for much of the journey) and singer George Michael were on the same flight. I felt lost.

From London it was on to Delhi, Chennai, and Mumbai. By day, I evaluated five-star private schools and colleges that were very definitely for the privileged. By night, I was put up in unbelievably salubrious and attentive five-star hotels. But in the evenings, sitting and chatting with street children outside these very same hotels, I wondered what effect any of my work could have on the poor, whose desperate needs I saw all around me. I didn’t just want my work to be a defense of privilege. The middle-class Indians, I felt, were wealthy already. To me it all seemed a bit of a con: just because they were in a “poor” country, they were able to latch onto this international assistance even though they as individuals had no pressing need for it at all. I didn’t like it, but as I returned to my room and lay on the 500-thread-count Egyptian-cotton sheets, my discomfort with the program was forced to compete with a mounting sense of self-criticism.

Then one day, everything changed. Arriving in Hyderabad to evaluate brand-new private colleges at the forefront of India’s hi-tech revolution, I learned that January 26th was Republic Day, a national holiday. Left with some free time, I decided to take an autorickshaw—the three-wheeled taxis ubiquitous in India—from my posh hotel in Banjara Hills to the Charminar, the triumphal arch built at the center of Muhammad Quli Shah’s city in 1591. My Rough Guide to India described it as Hyderabad’s “must see” attraction, and also warned that it was situated in the teeming heart of the Old City slums. That appealed to me. I wanted to see the slums for myself.

As we traveled through the middle-class suburbs, I was struck by the ubiquity of private schools. Their signboards were on every street corner, some on fine specially constructed school buildings, but others grandly posted above shops and offices. Of course, it was nothing more than I’d been led to expect from my meetings in India already—senior government officials had impressed me with their candor when they told me it was common knowledge that even the middle classes were all sending their children to private schools. They all did themselves. But it was still surprising to see how many there were.

We crossed the bridge over the stinking ditch that is the once-proud River Musi. Here were autorickshaws in abundance, cattle-drawn carts meandering slowly with huge loads of hay, rickshaws agonizingly peddled by painfully thin men. Cars were few, but motorbikes and scooters (“two-wheelers”) were everywhere—some carried whole families (the largest child standing in front; the father at the handlebars; his wife, sitting sidesaddle in her black burka or colorful sari, holding a baby, with another small child wedged in between). There were huge trucks brightly painted in lively colors. There were worn-out buses, cyclists, and everywhere pedestrians, whose cavalier attitude toward the traffic unnerved me as they stepped in front of us seemingly without a care in the world. From every vehicle came the noise of horns blaring—the drivers seemed to ignore their mirrors, if they had them at all. Instead, it seemed to be the responsibility of the vehicle behind to indicate its presence to the vehicle in front. This observation was borne out by the legend on the back of the trucks, buses, and autorickshaws, “Please Horn!” The noise of these horns was overwhelming: big, booming, deafening horns of the buses and trucks, harsh squealing horns from the auto-rickshaws. It’s the noise that will always represent India for me.

All along the streets were little stores and workshops in makeshift buildings—from body shops to autorickshaw repair shops, women washing clothes next to paan (snack) shops, men building new structures next to the stalls of market vendors, tailors next to a drugstore, butchers and bakers, all in the same small hovel-like shops, dark and grimy, a nation of shopkeepers. Beyond them all rose the 400-year-old Charminar.

My driver let me out, and told me he’d wait for an hour, but then called me back in a bewildered tone as I headed not to the Charminar but into the back streets behind. No, no, I assured him, this is where I was going, into the slums of the Old City. For the stunning thing about the drive was that private schools had not thinned out as we went from one of the poshest parts of town to the poorest. Everywhere among the little stores and workshops were little private schools! I could see handwritten signs pointing to them even here on the edge of the slums. I was amazed, but also confused: why had no one I’d worked with in India told me about them?

I left my driver and turned down one of the narrow side streets, getting quizzical glances from passersby as I stopped underneath a sign for Al Hasnath School for Girls. Some young men were serving at the bean-and-vegetable store adjacent to a little alleyway leading to the school. I asked them if anyone was at the school today, and of course the answer was no for it was the national holiday. They pointed me to an alleyway immediately opposite, where a hand-painted sign precariously supported on the first floor of a three-story building advertised “Students Circle High School & Institute: Registered by the Gov’t of AP.” “Someone might be there today,” they helpfully suggested.

I climbed the narrow, dark staircase at the back of the building and met a watchman, who told me in broken English to come back tomorrow. As I exited, the young men at the bean-and-vegetable counter hailed me and said there was definitely someone at the Royal Grammar School just nearby, and that it was a very good private school and I should visit. They gave me directions, and I bade farewell. But I became muddled by the multiplicity of possible right turns down alleyways followed by sharp lefts, and so asked the way of a couple of fat old men sitting alongside a butcher shop.

Their shop was the dirtiest thing I had ever seen, with entrails and various bits and pieces of meat spread out on a mucky table over which literally thousands of flies swarmed. The stench was terrible. No one else seemed the least bit bothered by it. They immediately understood where I wanted to go and summoned a young boy who was headed in the opposite direction to take me there. He agreed without demur, and we walked quickly, not talking at all as he spoke no English. In the next street, young boys played cricket with stones as wickets and a plastic ball. One of them called me over, to shake my hand. Then we turned down another alleyway (with more boys playing cricket between makeshift houses outside of which men bathed and women did their laundry) and arrived at the Royal Grammar School, which proudly advertised, “English Medium, Recognised by the Gov’t of AP.“ The owner, or “correspondent” as I soon came to realize he was called in Hyderabad, was in his tiny office. He enthusiastically welcomed me. Through that chance meeting, I was introduced to the warm, kind, and quietly charismatic Mr. Fazalur Rahman Khurrum and to a huge network of private schools in the slums and low-income areas of the Old City. The more time I spent with him, the more I realized that my expertise in private education might after all have something to say about my concern for the poor.

Khurrum was the president of an association specifically set up to cater to private schools serving the poor, the Federation of Private Schools” Management, which boasted a membership of over 500 schools, all serving low-income families. Once word got around that a foreign visitor was interested in seeing private schools, Khurrum was inundated with requests for me to visit. I spent as much time as I could over the next 10 days or so with Khurrum traveling the length and breadth of the Old City, in between doing my work for the International Finance Corporation in the new city. We visited nearly 50 private schools in some of the poorest parts of town, driving endlessly down narrow streets to schools whose owners were apparently anxious to meet me. (Our rented car was a large white Ambassador—the Indian vehicle modeled on the old British Morris Minor, proudly used by government officials when an Indian flag on the hood signified the importance of its user—horn blaring constantly, as much to signify our own importance as to get children and animals out of the way.) There seemed to be a private school on almost every street corner, just as in the richer parts of the city. I visited so many, being greeted at narrow entrances by so many students, who marched me into tiny playgrounds, beating their drums, to a seat in front of the school, where I was welcomed in ceremonies officiated by senior students, while school managers garlanded me with flowers, heavy, prickly, and sticky around my neck in the hot sun, which I bore stoically as I did the rounds of the classrooms.

So many private schools, some had beautiful names, like Little Nightingale’s High School, named after Sarogini Naidu, a famous “freedom fighter” in the 1940s, known by Nehru as the “Little Nightingale” for her tender English songs. Or Firdaus Flowers Convent School, that is, “flowers of heaven.” The “convent” part of the name puzzled me at first, as did the many names such as St. Maria’s or St. John’s. It seemed odd, since these schools were clearly run by Muslims—indeed, for a while I fostered the illusion that these saints and nuns must be in the Islamic tradition too. But no, the names were chosen because of the connotations to parents—the old Catholic and Anglican schools were still viewed as great schools in the city, so their religious names were borrowed to signify quality to the parents. But did they really deliver a quality education? I needed to find out.

One of the first schools Khurrum took me to was Peace High School, run by 27-year-old Mohammed Wajid. Like many I was to visit, the school was in a converted family home, fronting on Edi Bazaar, the main but narrow, bustling thoroughfare that stretched out behind the Charminar. A bold sign proclaimed the school’s name. Through a narrow metal gate, I entered a small courtyard, where Wajid had provided some simple slides and swings for the children to play on. By the far wall were hutches of pet rabbits for the children to look after. Wajid’s office was to one side, the family’s rooms on the other. We climbed a narrow, dark, dirty staircase to enter the classrooms. They too were dark, with no doors, and noise from the streets easily penetrated the barred but unglazed windows. The children all seemed incredibly pleased to see their foreign visitor and stood to greet me warmly. The walls were painted white but were discolored by pollution, heat, and the general wear-and-tear of children. From the open top floor of his building, Wajid pointed out the locations of five other private schools, all anxious to serve the same students in his neighborhood.

Wajid was quietly unassuming, but clearly caring and devoted to his children. He told me that his mother founded Peace High School in 1973 to provide “a peaceful oasis in the slums” for the children. Wajid, her youngest son, began teaching in the school in 1988, when he was himself a 10th-grade student in another private school nearby. Having then received his bachelor’s in commerce at a local university college and begun training as an accountant, his mother asked him to take over the school in 1998, when she felt she must retire from active service. She asked him to consider the “less blessed” people in the slums, and that his highest ambition should be to help them, as befitting his Muslim faith. This seemed to have come as a blow to his ambitions: his elder brothers had all pursued careers, and several were now living overseas in Dubai, London, and Paris, working in the jewelry business. But Wajid felt obliged to follow his mother’s wishes and so began running the school. He was still a bachelor, he told me, because he wanted to build up his school. Only when his financial prospects were certain could he marry.

The school was called a high school, but like others bearing this name, it included kindergarten to 10th grade. Wajid had 285 children and 13 teachers when I first met him, and he also taught mathematics to the older children. His fees ranged from 60 rupees to 100 rupees per month ($1.33 to $2.22 at the exchange rates then), depending on the children’s grade, the lowest for kindergarten and rising as the children progressed through school. These fees were affordable to parents, he told me, who were largely day laborers and rickshaw pullers, market traders and mechanics—earning perhaps a dollar a day. Parents, I was told, valued education highly and would scrimp and save to ensure that their children got the best education they could afford.

On my second visit, I arrived at Wajid’s school in time for morning assembly at 8:50 a.m. The event was completely run by the children, especially the senior girls. Wajid told me that the experience was important to ensure that they learned responsibility, as well as organizational and communication skills, from a very early age. The assembly began with about 15 minutes of calisthenics to the rhythm of drums played by the senior boys. Then there were ...