eBook - ePub

Beyond Liberal and Conservative

Reassessing the Political Spectrum

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Politicians and political analysts continue to use a single liberal-conservative dimension to analyze the ideological views of the American people, but that approach is increasingly inadequate. Professors Maddox and Lilie have gone beyond the liberal-conservative continuum. By separating questions aof economic policy from issues involving civil liberties, they find four basic ideological group: liberals, conservatives, libertarians, and populists. This book goes a long way toward explaining such phenomena as ticket-splitting, the impact of the baby-boom generation, and the internal conflicts both major parties will face over the next few years.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Beyond Liberal and Conservative by William S. Maddox, Stuart A. Lilie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

VI. Mass Belief Systems and Political Behavior

Thus far we have described the state of American public opinion in terms of four types of mass belief systems or ideological categories. In the previous chapter we analyzed the social bases of support for those ideologies and offered some demographic explanations of the changing proportions of support for each category. This four-way analysis of American politics, however, differs from that suggested by most political observers and in some crucial ways is at odds with the way the U.S. political system is defined by political leaders in their public statements. Put more bluntly Americans live in a dichotomized political world according to conventional definitions; liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans-these are the labels presented to citizens again and again by the mass media, political leaders, and political scientists. It is our aim in this chapter to describe how far mass belief systems are expressed in that dichotomous world.

What do people do when faced with the either/or choices presented to them, especially when there are two large groups, popu- lists and libertarians, whose ideas are not even superficially addressed by most political elites? To answer this question, we first examine the crucial issue of voter turnout differences between groups and then analyze the actual voting behavior that different ideological types demonstrate in response to the choices presented them. We then look at their level of involvement in or alienation from politics in general. A diverse public, when offered simplistic and not necessarily useful choices in politics, may avoid the process, do the best they can, or develop feelings of alienation from the entire political system. It is these possibilities we explore in this chapter. Finally we present some brief evidence as to how well our four ideological labels can be used to describe the voting behavior of members of Congress. At this point we will see that populism and libertarianism do find some expression in the congressional system, although it is underrepresented as compared to the levels of public support for those views.

Ideology and Voting Behavior

It is a truism of political science that opinions must be translated into action before they can affect the American political system. The extension of this idea is that majority viewpoints may not influence government activity and that minority viewpoints may be dominant if the levels of activity vary enough between groups. Therefore we must consider our four ideological types in the same manner. How have they translated their points of view into political action through the basic mechanism of the vote? Those who vote more frequently may have more impact on the political system. Unfortunately we cannot study the voting behavior of our ideological types in every possible situation, that is in state and local elections, but we can present some interesting evidence as to how they behave in national elections.

Table 12 lists the reported voting turnout level of each of the four groups (plus the divideds and the inattentives, as they provide an interesting comparison).

Comparisons over the period from 1972 to 1980 reveal some interesting and possibly crucial trends in terms of a basic political act, that of voting in national elections. Populists vote at a slightly below average level across this time period. As populists come from those social groups that historically do not vote as often (lower educated and lower income, for example), the ideological view of populism is underrepresented in the electorate for national elections. Conversely libertarians could be expected to vote at a higher-than-average level in that they tend to be among the highly educated and more affluent types of people who do vote more often. This in fact is the case, with some variations across years. In 1980 libertarians vote at a rate 10 percent higher than that of the rest of the voting population. In the conservative and liberal categories there are interesting changes evident for the 1970s. In eight years conservatives move from slightly below to 11 percent above the national average. Liberals move in the opposite direction, shifting from an above-average to a below-average turnout level. These figures suggest that liberals are the disenchanted of the recent decade. Although they still come from social categories that are more likely to vote, their response to the changing political climate of the 1970s has been a slight withdrawal from participation. The recent success of the conservatives, especially in the 1980 presidential election, in part reflects their increasing participation, in effect filling the void left by liberal voters.

Table 12

REPORTED VOTER TURNOUT OF IDEOLOGICAL CATEGORIES, BY COMPARISON WITH NATIONAL AVERAGE, BY PERCENT

| Ideological Category | 1972 | 1976 | 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Libertarian | +6 | +4 | +10 |

| Conservative | -1 | +6 | +11 |

| Populist | -6 | -5 | -3 |

| Liberal | +4 | +2 | -3 |

| Divided | +8 | +3 | 0 |

| Inattentive | -22 | -18 | -34 |

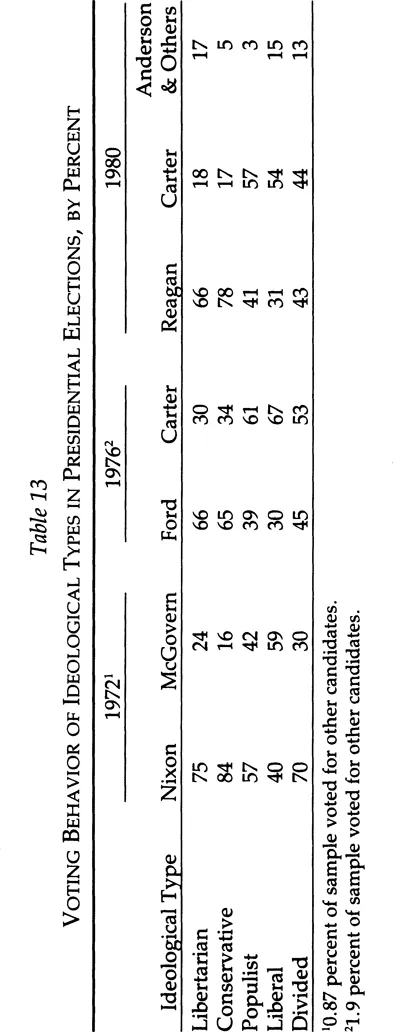

Presidential Voting, 1972 to 1980

We look now at the voting behavior of ideological types in presidential elections, presented in table 13. As a caveat to our analysis we must note that a true ideologue of course would have had some difficulty in expressing his opinions through presidential candidacies of recent years. Most political observers saw George McGovern in 1972 as presenting a fairly straightforward liberal candidacy and Ronald Reagan in 1980 as presenting the conservative opposite; otherwise, however, the ideological leanings of candidates during the 1970s have not been all that clear. Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, John Anderson, and Jimmy Carter were often accused of being ideologically lacking, more pragmatic in their approaches to political issues. Nixon, sometimes defined as a true conservative, was at the same time a government activist, especially in regard to foreign affairs. He even instituted wage and price controls, hardly the action of a conservative. Ford, although he vetoed spending bills from the Democratic Congress, never seemed to epitomize traditional conservatism as clearly as did Reagan or Barry Goldwater. Jimmy Carter dominated presidential politics in the Democratic party through two elections and yet never attracted a definite ideological constituency; he drew from various wings of the party but never really symbolized an ideological point of view. (By our definitions Carter's moralism with regard to personal freedoms and rhetorical commitment to fiscal conservatism would label him a conservative. By his actions, however, he took few actions to limit government intervention in the economy, supported many interventionist programs, and took few initiatives to enforce his moralism, leaving his record more like that of a traditional liberal, although an uncomfortable one.} John Anderson, through his independent candidacy in 1980, offered an alternative to many Americans, but the campaign itself defined his ideological views very little beyond his career-long definition as a "moderate" or liberal Republican.

How did the voters respond to these choices? In 1972 ideological choices were fairly clear for conservatives; they overwhelmingly supported Nixon over McGovern. The small proportion of libertarians that year also supported Nixon very strongly. Liberals, on the other hand, gave McGovern his highest level of support but it constituted a far-from-overwhelming endorsement; a significant number of liberals supported Nixon. It was among populists that the battle was most evenly fought; populists had to choose between two candidates who split in exactly an opposite direction from the one they would have felt comfortable with: Nixon was the social conservative populists would have liked but he attacked the economic initiatives associated with populism. McGovern was of little help to populists; his economic liberalism was less appealing when combined with lenient positions on personal freedom issues. Thus it is not surprising that populists were the most divided group in 1972.

The ideological views of presidential candidates were even less clear in 1976, as a Democrat with undefinable ideological characteristics faced a Republican whose performance in office had not excited conservative support. Each of the four ideological groups split in surprisingly similar proportions. Ford drew about 66 percent of the support of both libertarians and conservatives, apparently drawing most of his support in response to his advocacy of economic nonintervention. Carter, on the other hand, drew 67 percent support from liberals and 61 percent from populists, again apparently converting traditional Democratic arguments for economic intervention into votes. Neither candidate, however, was shut out in any ideological category; each drew at least 30 percent from each group. As we suggested in chapter II, this may be a classic case of ideological American voters looking at two unclear ideological statements from candidates and simply making the best choice they could.

The 1980 battle was more ideological in tone as Reagan clung to his articulation of conservative principles, leaving Carter defined as a liberal almost by default. Carter was not a McGovern-type liberal, however, and often sought to battle Reagan on his own ground in terms of economic minimalism. Neither stressed the expansion of personal freedoms as a goal, although Reagan did emphasize his commitment to "traditional values," often viewed as a code phrase for a less tolerant view toward personal freedom and alternative lifestyles. The situation was further confused by the presence of independent John Anderson, who offered voters an alternative to the two ...

Table of contents

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- I. THE ROOTS OF CONTEMPORARY IDEOLOGIES

- II. THE EMPIRICAL STUDY OF IDEOLOGY AND MASS BELIEF SYSTEMS

- III. ISSUES IN AMERICAN POLITICS: 1952-80

- IV. THE DISTRIBUTION OF IDEOLOGY IN AMERICA

- V. THE DEMOGRAPHIC BASIS OF IDEOLOGICAL GROUPS

- VI. MASS BELIEF SYSTEMS AND POLITICAL BEHAVIOR

- VII. IDEOLOGY AND FOREIGN POLICY

- VIII. AMERICAN POLITICS: A FRAGMENTED FUTURE?

- APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY

- REFERENCES