Poverty and Sustainable Development in Asia

Impacts and Responses to the Global Economic Crisis

- 542 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Poverty and Sustainable Development in Asia

Impacts and Responses to the Global Economic Crisis

About this book

This joint publication from the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank Institute features selected papers from the September 2009 conference on the social and environmental impact of the global economic crisis on Asia and the Pacific, especially on the poor and vulnerable. The publication is designed with the needs of policy makers in mind, utilizing field, country, and thematic background studies to cover a large number of countries and cases. This publication suggests that the crisis is an opportunity to rethink the model of development in Asia for growth to become more inclusive and sustainable. Issues that need to be more carefully considered include: closing the gap of dualistic labor markets, building up social protection systems, rationalizing social expenditures, addressing urban poverty through slum upgrading, promoting rural development through food security programs in pro-poor growth potential areas, and concentrating climate change interventions on generating direct benefits for the environments of the poor.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

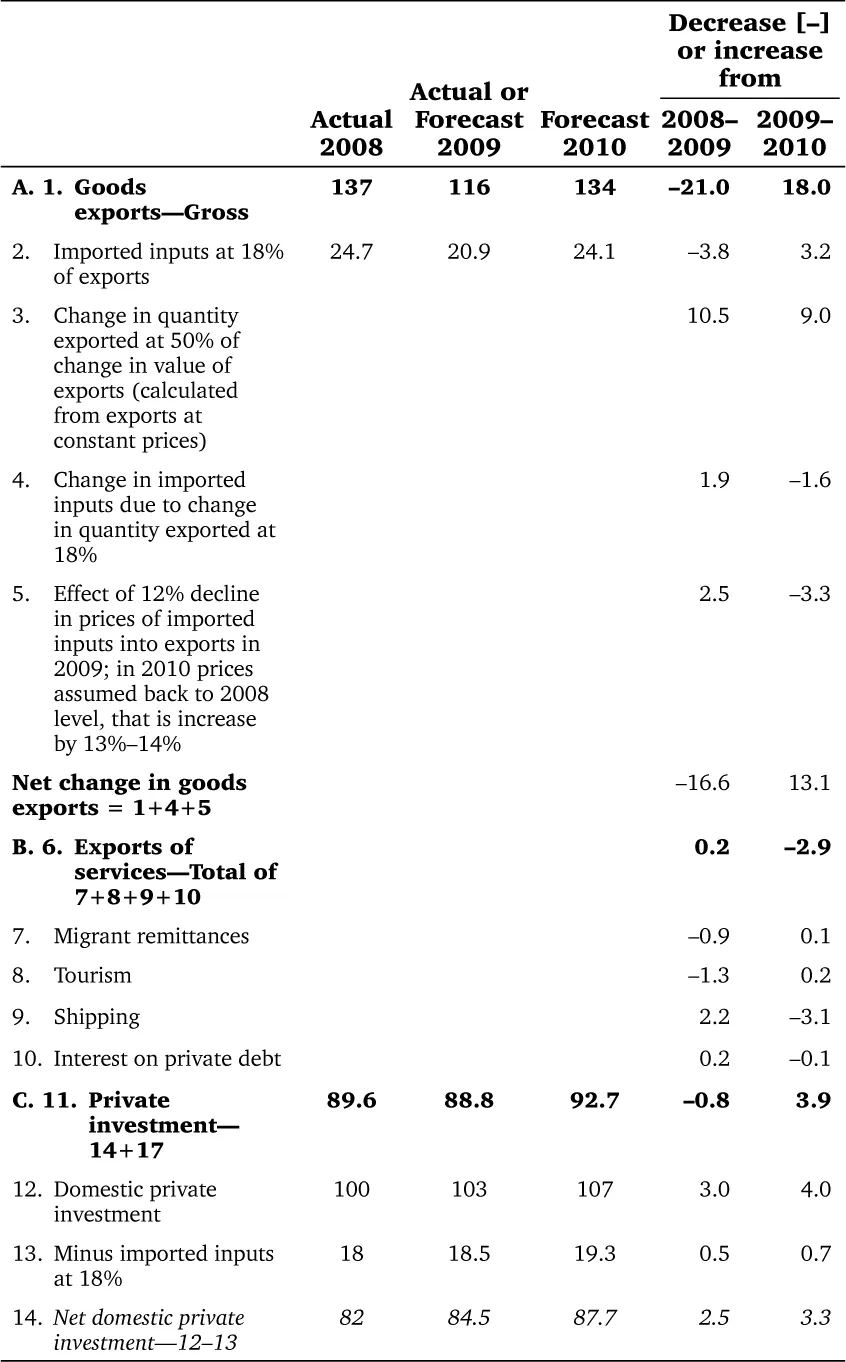

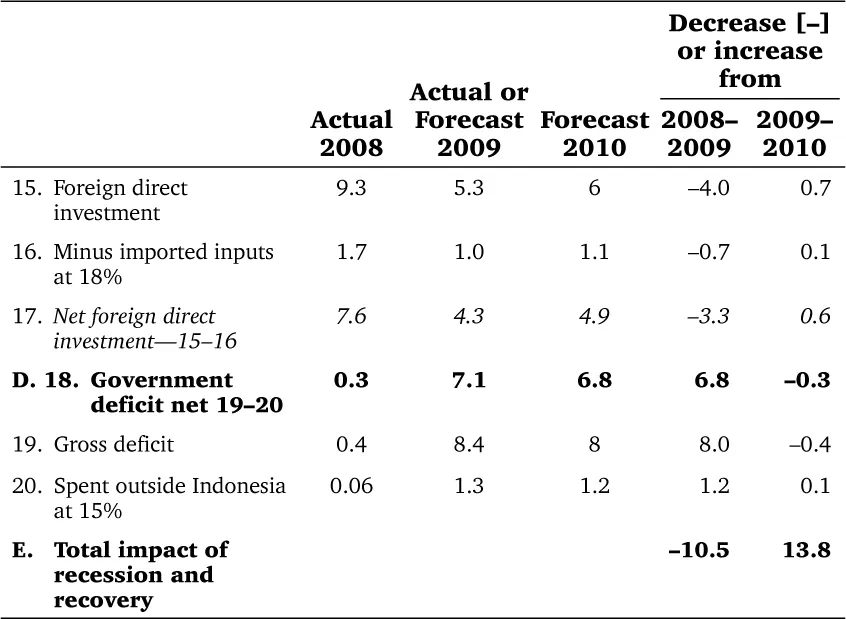

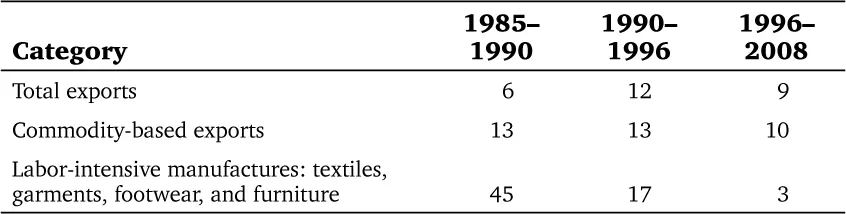

The impact of the world recession on Indonesia and an appropriate policy response: Some lessons for Asia

Introduction

1. The recession and Indonesia—A surprisingly small macroeconomic impact

2. Aggravation of unemployment and underemployment

Few “real” jobs added since 1997

Change (million) | 1985–1997 | 1997–2008 |

Employed in manufacturing and constructiona | 7.5 | 2.5 |

Employed in transport, communication, utilities | 3.3 | 3.1 |

Able to obtain productive work (a) | 10.8 | 5.6 |

Agriculture | 1.7 | 5.5 |

Trade and services | 12.2 | 4.5 |

Added to work- and income-sharing or underemployed (b) | 13.9 | 10.0 |

Unemployed (c) | 2.3 | 3.1 |

Migrants—guesstimate (d) | 1.3 | 3.5 |

Total added to labor force (each period) (a+b+c+d) | 28.2 | 22.2 |

Added to unemployed, underemployed, migrants 1997–2008 (b+c+d) | 16.6 | |

Added to the labor force in 2009 and unlikely to a find job | 2.0 | |

Estimated job losses in labor-intensive exports alone | 0.4 | |

Estimated added to unemployed and underemployed, 1997–2009 | 19.0 |

Job losses and lack of job creation

Failure to create jobs since 1997

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Boxes

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- Overview

- The impact of the world recession on Indonesia and an appropriate policy response: Some lessons for Asia

- Impacts of the economic crisis in East Asia: Findings from qualitative monitoring in five countries Carrie Turk and Andrew Mason

- Social impact of commodity price volatility in Papua New Guinea Dominic Patrick Mellor

- Assessing social outcomes through the Millennium Development Goals Shiladitya Chatterjee and Raj Kumar

- The impact of the global economic slowdown on value chain labor markets in Asia Rosey Hurst, Martin Buttle, and Jonathan Sandars

- Global meltdown and informality: An economy-wide analysis for India—Policy research brief Anushree Sinha

- The social impact of the global recession on Cambodia: How the crisis impacts on poverty Kimsun Tong

- Women facing the economic crisis— The garment sector in Cambodia Sukti Dasgupta and David Williams

- No cushion to fall back on: The impact of the global recession on women in the informal economy in four Asian countries Zoe Horn

- Gender and social protection in Asia: What does the crisis change? Nicola Jones and Rebecca Holmes, with Hannah Marsden, Shreya Mitra, and David Walker

- The impact of the global slowdown on the People’s Republic of China’s rural migrants: Empirical evidence from a 12-city survey Xiulan Zhang and Steve Lin

- Urban–rural and rural–urban transmission mechanisms in Indonesia in the crisis Megumi Muto, Shinobu Shimokoshi, Ali Subandoro, and Futoshi Yamauchi

- The global financial crisis and agricultural development: Viet Nam Dang Kim Son, Vu Trong Binh, and Hoang Vu Quang

- Impact of the global recession on international labor migration and remittances: Implications for poverty reduction and development in Nepal, Philippines, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan Andrea Riester

- Global crisis and fiscal space for social protection Armin Bauer, David E. Bloom, Jocelyn E. Finlay, and Jaypee Sevilla

- Addressing unemployment and poverty through infrastructure development as a crisis-response strategy Chris Donnges

- Fiscal space for social protection policies in Viet Nam Paulette Castel

- The global economic crisis: Can Asia grasp the opportunity to strengthen social protection systems? Mukul G. Asher

- Income support in times of global crisis: An assessment of the role of unemployment insurance and options for coverage extension in Asia Wolfgang Scholz, Florence Bonnet, and Ellen Ehmke

- Financial crisis and social protection reform—Brake or motor? An analysis of reform dynamics in Indonesia and Viet Nam Katja Bender and Matthias Rompel

- Reforming social protection systems when commodity prices collapse: The experience of Mongolia Wendy Walker and David Hall

- The impact of the global recession on the health of the people in Asia Soonman Kwon, Youn Jung, Anwar Islam, Badri Pande, and Lan Yao

- The impact of the global recession on the poor and vulnerable in the Philippines and on the social health insurance system Axel Weber and Helga Piechulek

- Implications of economic recessions on quality, equity, and financing of education Jouko Sarvi

- Impact of the global recession on sustainable development and poverty linkages V. Anbumozhi and Armin Bauer

- Green growth, climate change, and the future of aid: Challenges and opportunities in Asia and the Pacific Paul Steele and Yusuke Taishi

- Measuring the environmental impacts of changing trade patterns on the poor Kaliappa Kalirajan, Venkatachalam Anbumozhi, and Kanhaiya Singh

- Poverty, climate change, and the economic recession Benoit Laplante

- Alternative energy options of Asia in crises Kaoru Yamaguchi and Miki Yanagi

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app