![]()

Section 1

Supply, Demand, and the Technologies

![]()

Chapter 1

Energy, Environment, and Rural Development: Why Rural Biomass Energy Matters

The past 30 years have witnessed the fastest rate of economic development in the history of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Accounting for 20% of the world’s population, the nation of 1.3 billion people has transformed from a primarily agrarian economy to a highly industrialized one. This rapid change and growth is expected to continue, and with it all the economic, environmental, and social difficulties, contradictions, and problems that other countries have experienced during industrialization. Except, in the PRC, because of the rapid rate of change and the population factor, these changes are occurring in a much more concentrated and intense manner than what has been experienced elsewhere.1

In particular, energy security in rural areas, rural environmental challenges, and urban-rural inequality are constraints on the government’s ability to achieve its socioeconomic development objectives. Ultimately, the country must rebalance its economic development so that its rural population, agricultural sector, and environment also benefit from this growth. To make this happen, the TA study found that the government must invest in rural energy, particularly biomass-based energy, which can convert agricultural wastes into various energy forms, such as biogas, fuels, and electricity. No developed country has significantly reduced poverty and sustained growth without improving households’ access to energy.

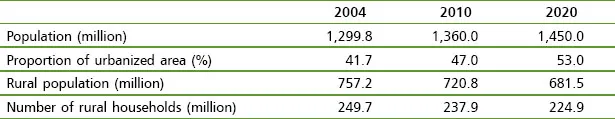

Table 1.1: PRC Population Trends (2004–2020)

Source: National Population Development Strategy Report. 2006. Available: www.china.com.cn

Energy Demand

As a result of increasing industrialization, urbanization, and socioeconomic development, the PRC’s overall demand for energy has skyrocketed. The PRC is already the second largest energy producer and consumer in the world. In 2008, the country produced 2.6 billion tons of coal equivalent (tce) of primary energy and consumed 2.85 billion tce. In the same year, coal accounted for 68.7% of the PRC’s total energy consumption, whereas oil accounted for 18.7%, natural gas 3.8%, and hydropower 8.9%.2

Driven by a huge increase in the number of privately-owned vehicles, the PRC alone accounted for more than 30% of the world’s incremental consumption of liquid fuels in the past two years.3 The number of private vehicles in the PRC more than doubles every five years, increasing from 300,000 private vehicles in 1980 to 46 million in 2009.

In 2006, the 11th Five-Year Plan set a target for a 20% cut in the energy intensity of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of 2010. The start was slow, but by the end of 2008, it had managed 10% and it now looks on track for its target. This would mean a reduction in carbon emissions of 1.5 billion tons per year by 2010.4

More alarming, the energy intensity of the PRC’s economy, measured by primary energy use per unit of GDP (at constant prices), began creeping back during the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005) after a long decline starting in the late 1970s. While this is closely related to the strong growth of energy-intensive industries, it also underscores the government’s continued difficulty in implementing its well-expressed sustainable development strategies. If the PRC’s energy intensity had stayed on its descending course, over 1 billion tons of coal consumption could have been avoided between 2001 and 2005.5 That would have prevented about 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions and 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. The power of energy efficiency multiplies in a fast growing economy.

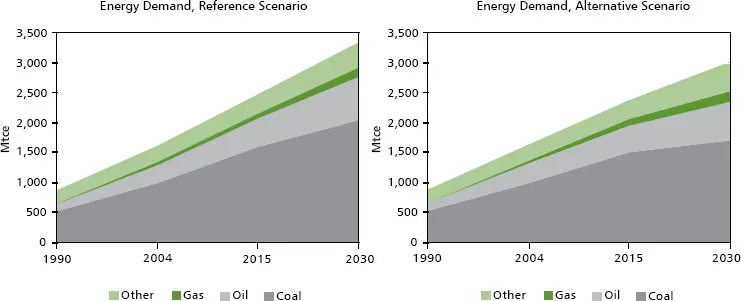

The PRC’s energy track for the next 20 years is laden with coal and oil. Figure 1.1 shows the impact that policy can have on coal dependency. According to the International Energy Agency, policies that are pro-energy efficiency and pro-renewable energy can lead to a decline in the PRC’s coal dependence (as shown in the “Alternative Scenario” in Figure 1.1). If the current trends and policies continue, though, the share of coal will even increase in the mid term (2015) (the “Reference Scenario” in Figure 1.1).6

Figure 1.1: PRC Energy Consumption Scenarios, 1990–2030 (million tce)

Mtce = million tons of coal equivalent.

Source: World Energy Outlook. 2006. International Energy Agency.

Showing an understanding of the current energy challenges, PRC President Hu Jintao said at the Beijing International Renewable Energy Forum in 2005, “Exploration and utilization of renewable energy is the only way to deal with the increasingly severe problems of energy shortage and environmental pollution, and it is also the only way to the sustainable development of our society.” And the structure of the PRC’s energy production is indeed likely to shift toward a more renewable path, according to the country’s commitments expressed before the Copenhagen climate talks in December 2009.

Rural energy demand. By 2008, 50% of the rural population in the PRC—about 100 million households—still relied on burning wood and agricultural crop wastes (residues) for cooking and heating. According to the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) statistics, rural energy consumption in 2008 was nearly 125% higher than 1980s levels, representing an average annual increase of 2.9%. During that same period, consumption of commercial energy increased four-fold.

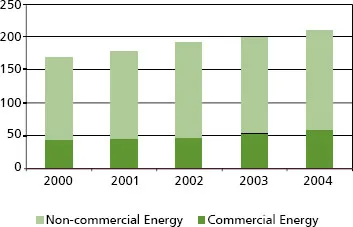

From 1980 to 2004, though, commercial energy consumption (such as processed coal and liquefied petroleum gas [LPG]) has been gradually rising as compared to that of non-commercial energy (directly burning coal, firewood, biomass). To be more precise, rural energy consumption in 2004 was nearly 480 million tons of coal equivalent (mtce), of which 209 mtce was used at the household level. Out of that 209 mtce, about 59.15 mtce is commercial energy, accounting for about 3% of the national total (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Household Energy Consumption by Rural Residents (million tce)

Source: ADB. 2006. Technical Assistance to the People’s Republic of China for Preparing National Strategy for Rural Biomass Renewable Energy Development. Manila.

The 209 mtce used at the household level can be further understood according to its uses. The TA study conducted a detailed analysis of rural households’ energy sources and uses, finding that cooking and water heating account for the majority of rural energy demand (62%). Space heating is a distant second (33%). Of the 209 mtce used by households in 2004, about 129 mtce went to cooking and water heating. An estimated 3.56 megajoules (MJ) of energy was consumed in 2004 for cooking and water heating per capita per day in rural areas.

“Exploration and utilization of renewable energy is the only way to deal with the increasingly severe problems of energy shortage and environmental pollution, and it is also the only way to the sustainable development of our society.”

—Pres. Hu Jintao

The proportion of energy consumed for cooking and water heating is higher because of the inefficiency of both the resource being used (straw and firewood) and the end-use device. While still high, the 2004 consumption-demand figure already represented wide utilization of energy-saving household stoves. By the end of 2004, the PRC had promoted energy-saving firewood stoves in 190 million rural households—70% of all households, including commercialized stoves in 46.5 million households. The energy-saving stoves have a thermal efficiency twice that of indigenous stoves.

Much of the remaining balance on that 209 mtce used by households in 2004—70 mtce—was used for space heating, of which straw, firewood, and coal are the main fuels. Firewood stoves (kang) and coal stoves are mainly used for heating. Of that 70 mtce for space heating, firewood stoves consumed 53.13 mtce and coal stoves consumed 16.35 mtce.7 One third of the country’s population live in the two coldest regions, requiring space heating.8 The country’s vast territory, though, means that great differences exist in the need and means of heating (as well as air conditioning). For example, in January, the northernmost region is about 40°C lower than the southernmost region.

The TA study also warned that as energy becomes more affordable, households will use more of it to heat their homes. The annual number of heating days, according to the TA study, could increase by 27%, from about 110 days in 2010 to 140 days in 2020.

With nearly 98% of the country’s rural areas having access to electricity for lighting and appliances, total electricity consumption by rural residents in 2004 reached 35.8 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) for lighting and 498.21 billion kWh for appliances. From 2000 to 2005, the number of appliances per 100 rural residents increased as follows: 35.3 more televisions for a total of 84, 7.8 more refrigerators for a total of 20.1, and 11.6 more washing machines for a total of 40.2.

Despite these trends, about 30 million people (8 million households) across 20,000 villages still rely on kerosene lamps for lighting because there is no public grid connection. In pastoral areas of Inner Mongolia, people generate power from windmills or diesel engines. In regions with plentiful water resources but no public grid connection, such as Guizhou Province, people generate electricity from mini-hydropower generators.

Future projected energy use. To model rural energy needs in the future, the study developed three scenarios based on degrees of changes to the energy structure and the achievement of policies related to end-use energy efficiency (and also based on assumptions regarding population changes and rising incomes and living standards).

| (i) | Low pro-renewable scenario. Reforms and energy efficiency do not achieve projected levels because of failed market reforms and non-sustainable implementation, sending rural energy consumption on a steep incline. |

| (ii) | Medium pro-renewable scenario. State policy is enforced and energy conservation and renewable energy are promoted with the effect of slowing rural energy consumption to more moderate level of increase. |

| (iii) | Sustainable pro-renewable scenario. The government institutes strong policies and... |