This is a test

- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This report was prepared with the primary objective of drawing insights on how Asian economic giants India and the People's Republic of China leveraged education and skills development to advance economic growth. The analysis presented similarities and differences in human capital development strategies and their outcomes that helped define development pathways between the two countries. It also outlined the prospects for human capital development in the sustainability of the two countries' economic growth. The report was completed in 2014 under the Development Partnership Program for South Asia: Innovative Strategies for Accelerated Human Resource Development in South Asia (TA-6337 REG).

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Human Capital Development in the People's Republic of China and India by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Vocational Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Vocational EducationCHAPTER 2

Human Capital Development, Achievements, and Gaps

As the two most populous countries in the world, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India have been successful in improving their stock of human capital, in terms of both educational attainment and skills development in the last 5 decades (1960–2010). This was mainly due to substantial improvements in education and skill development investments, supported with better policies and institutions. However, disparities in educational opportunities as well as in achievements remain. Employability of graduates also poses a significant challenge.

A. Literacy, School Enrollments, and Educational Attainment

The PRC and India have achieved critical improvements in literacy—the basic determinant of the quality of life and the quality of the labor force—as well as in enrollment in primary education. In recent years, the literacy rate among the population aged 15 years and above has increased to 95% in the PRC and over 60% in India.

The gender disparity in the literacy rate has declined over time, but significant disparity still remains. Data as of 2006 show that in India, 75% of males aged 15 years and above can read and write short, simple statements on their everyday life with understanding, whereas only 51% of females in the same cohort can do the same (World Bank 2014). In the PRC, the gender disparity in literacy rates is significantly lower—98% of males and 93% of females aged 15 years and above were literate as of 2010 (World Bank 2014).

India has recorded substantial improvements in gross enrollment rate (GER) at all levels. Its primary GER has increased to over 100% in recent years, from only 78% for the total population and 61% for females in the 1970s (World Bank 2014). Its secondary and tertiary GERs have considerably increased as well, but they are still low (secondary level, 68.5%; tertiary level, 23%).

As shown in Figure 5, outstanding improvements in enrollment rates were also achieved by the PRC, especially at the primary and secondary levels. Its secondary GER jumped from about 20% in 1970 to 87% in 2010. The share of students enrolled in higher education, including higher vocational education, increased to more than 24% by 2010 from only about 3% in the early 1980s. Interestingly, the PRC has a higher level of secondary enrollment rates than India, though there is no gap in tertiary enrollment rates between the two countries.

Figure 5: Gross Enrollment Ratios by Level

(%, 1960–2010)

(%, 1960–2010)

Source: Author’s estimates based on United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), various years. Statistical Yearbook. Paris.

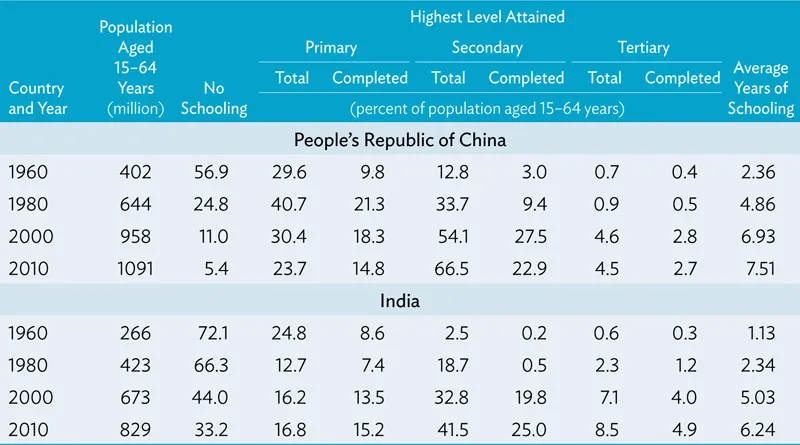

Alongside increases in school enrollments across all levels, substantial improvements in the educational attainment of the labor force were also seen in both countries. In 2010, 66.5% of the population aged 15–64 years in the PRC have either reached or completed secondary level, while 4.5% have advanced to the tertiary level (Table 2). This means that the PRC currently has a strong stock of workers with secondary education, and to a lesser extent, with tertiary-level education. The share of students enrolled in higher education, including higher vocational education, increased to more than 24% by 2009 from only about 3% in the early 1980s (World Bank 2012).

Table 2: Educational Attainments in the People’s Republic of China and India

Source: R.J. Barro and J.-W. Lee. 2013. A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics. 104. pp. 184–198.

In India, in the population aged 15–64 years,41.5% have secondary education and 8.5% have tertiary education. Interestingly, while the share of the labor force in India with secondary education is only about 60% that of the PRC, India has a greater stock of workers with tertiary education (7.1 million) than the PRC (4.9 million). However, one-third of the working-age population in India has no schooling. This is very high compared to only 5.4% in the PRC.

From 1960 to 1980, the average years of schooling among the population aged 15–64 years increased by 1.2 years in India, and by 2.5 years in the PRC (Table 2). From 1980 to 2010, it increased by almost 4 years in India, and by around 2.6 years in the PRC. Overall, the average years of schooling increased by over 5 years in both India and the PRC in the past 5 decades.

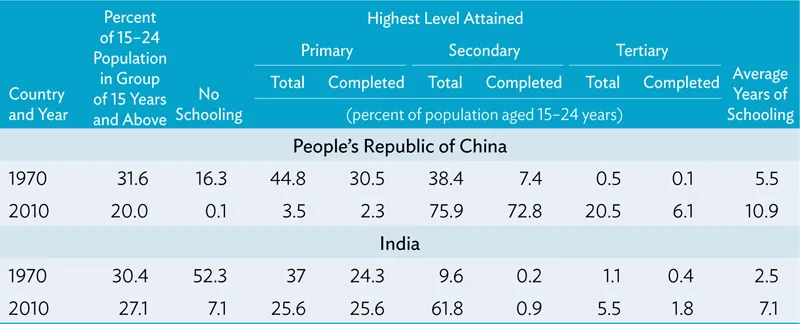

Higher enrollment rates had resulted in a dramatic decline in the proportion of the population aged 15–24 years with no schooling in both countries between 1970 and 2010 (Table 3). It went down from 16.3% to only 0.1% in the PRC, and from 52.3% to 7.1% in India. Enrollment gains are high both at the secondary and tertiary levels in the PRC, but mostly at the secondary level in India.

Table 3: Educational Attainments of Population Aged 15–24 Years in the People’s Republic of China and India

Source: J.-W. Lee and R. Francisco. 2012. Human Capital Accumulation in Emerging Asia, 1970–2030. Japan and the World Economy. 24 (2). 76–86.

Various factors have contributed to making the conditions in both the PRC and India favorable for human capital development. Nonetheless, achieving significant improvements in enrollment rates and educational attainment have been largely due to the education policies implemented in both countries. Because of its Compulsory Education Law2 in the mid-1980s, the PRC has made great progress toward expanding access to post-basic education in recent years and its goal of making primary and junior secondary schooling universal in the country (World Bank 2012).

In India, the constitutional right of universal free and compulsory education3 was deferred until 2009, when the Parliament of India enacted The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, or Right to Education Act, one of the most significant education reforms in India in recent decades (Government of India 2011a, Jones and Ramchand 2013).

The Right to Education Act provides for the right to free elementary education for 6- to 14-year-olds in neighborhood schools, including textbooks, uniforms, and other indirect costs (Government of India 2013, Jones and Ramchand 2013). It also provides for the compliance with improvement in school infrastructure, a fixed student–teacher ratio, and a 25% reservation for the economically disadvantaged communities in admission to private schools, among others.

Another factor that contributed to the significant educational achievements is the strong household demand for education. Empirical literature has identified the role of both income and nonincome factors for educational investments.4 For instance, Fredriksen and Tan (2008) suggest that aside from having strong public institutions, rapid economic growth and a more equal income distribution facilitated the educational investments in the Republic of Korea and Singapore, among other things. Higher income for more families implies that more families can afford to invest in the education of their children.

A cross-country analysis by Lee and Francisco (2012) covering a sample of 80 countries worldwide, including the PRC and India, confirmed this. They found that secondary and tertiary enrollment rates were positively related to per capita income, parental education, and public education expenditure between 1970 and 2010 and negatively related to income inequality and total fertility rate.

All these factors have favorably improved in both the countries during this period, and have arguably contributed to the improvements in their enrollment rates. For instance, the average gross domestic product per capita has increased to almost 22 times its initial level in the PRC between 1970 and 2010 (from $131 in constant 2005 $ purchasing power parity to $2,...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables, Boxes, and Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- I. Overview

- II. Human Capital Development, Achievements, and Gaps

- III. Human Development and Economic Growth

- IV. Labor Supply and Education: Prospects and Challenges

- V. Skill Upgrading and Wage Inequality: A Microdata Analysis

- VI. Policy Challenges and Recommendations for Human Capital Development

- References

- Back Cover