This is a test

- 115 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book focuses on local government's role in increasing city competitiveness through planning, governance, and finance, particularly in small to medium-sized cities in South Asia. Existing studies on city competitiveness tend to focus on megacities, and yet smaller cities house an increasingly large portion of South Asia's population. This study seeks to initiate a more systematic thinking on the role of planning, governance, and finance to overcome the challenges of urbanization, improve the investment climate, and provide greater opportunities for more people, especially in small to medium-sized cities.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Gearing Up for Competitiveness by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Why Planning, Governance, and Finance Matter for City Competitiveness

Planning and Competitiveness

Research and consultations carried out in the framework of this study indicate that there are three types of planning with significant impacts on city competitiveness: (i) local economic development (LED) planning, (ii) land use planning, and (iii) physical or investment planning.

(i) Local economic development planning. Economic policies developed at the state or central level with little contribution from local government, such as macroeconomic or industrial policies, have important consequences on city competitiveness. However, our focus in this study is on LED planning, with local government as the drivers to identify regional and local comparative and competitive advantages, and to work with others to develop a shared vision and plans that build on those strengths. Larger cities often have an agency dedicated to LED planning (and implementation in some cases), such as the New York City Economic Development Corporation (Box 1); while smaller cities may instead have a department or a dedicated person in the mayor’s office.

Box 1: New York City Economic Development Corporation

The New York City Economic Development Corporation’s mission is to encourage economic growth throughout the five boroughs of New York City by strengthening the city’s competitive position and facilitating investments that build capacity, create jobs, generate economic opportunity, and improve quality of life. They advise the city on policies, programs, and strategies to ensure that New York remains a global center of commerce and culture, and to attract and retain world-class companies and professionals.

By leveraging partnerships between public and private sectors, it helps to create affordable housing, new parks, shopping areas, community centers, cultural centers, and other facilities.

Source: New York City Economic Development Corporation. www.nycedc.com

The role of local government in coordinating and facilitating local economic development is critical for city competitiveness. The goal is not to manipulate markets or to assume a top-down economic planning function. Rather, the goals are to (i) understand the dynamics of a city’s economy, (ii) define the economic vision, (iii) identify demand for investments, and (iv) determine how public resources and public and private partnerships may be best channeled to achieve the vision and further spur growth.

The latter point is essential to helping local government create the best possible conditions for industry, entrepreneurs, and innovators. A sustainable economic vision should also balance environmental and social considerations, as these have direct impacts on sustainability, quality of life, and ultimately, city competitiveness (Box 2). LED planning is challenging and needs to remain flexible, particularly since demographic and economic trends shift over time. But this is why it is critical for local government to seek to understand its local economy and its relationship with other markets—so that it can anticipate demand for land and services.

Box 2: Singapore’s Targets

By 2030, Singapore aims to have at least 80% of its households within a 10-minute walk of a mass rapid transit station, and 90% within 400 meters of a park. This vision for growth, coupled with increased quality of life, requires a clear plan, strong leadership, and interagency collaboration.

Source: Singapore Urban Redevelopment Authority. Draft Master Plan 2013. Singapore.

Local governments need to (i) understand different types of investors’ objectives and the features they are looking for in a city, and (ii) identify what types of businesses and investment the city would like to attract, and is likely to attract, to implement its vision.

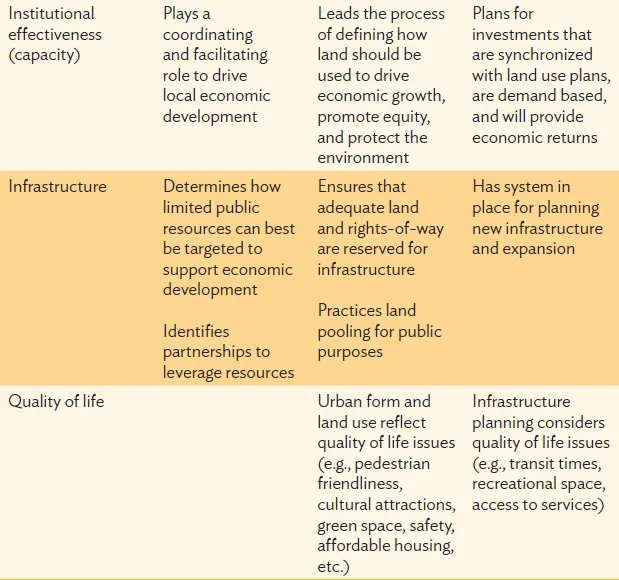

To attract entrepreneurs, cities and city leaders must be entrepreneurial themselves.4 To raise their level of competitiveness they must understand their competitive advantages and economic potential. This understanding may then be used to develop an informed and strategic economic vision that is linked to and articulated by a city’s other “tools”—land use and physical planning (Box 3)—which may then be geared to boosting city competitiveness. The integration and harmonization of economic, land use, and physical planning lays the foundation for local government to drive city competitiveness (Table 4). In many cases, urbanization is happening or has happened without a blueprint. But not all blueprints are equal. The blueprints themselves must be geared to city competitiveness objectives in order for cities to sustain and increase their dynamism.

Box 3: Wider Role for Planning

In the United Kingdom, the planning system is increasingly promoting the role of planning as coordinator, integrator, and mediator of the spatial dimensions of wider policy streams. Examples of relevant policy streams for the urban sector might include affordable housing or reduction of carbon emissions, but can also include public health issues.

Source: University of Manchester and University of Sheffield. 2008. Measuring the Outcomes of Spatial Planning in England. Executive Summary. http://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/6008/Executive-Summary.pdf

Table 4: Key Links between Competitiveness and Economic, Land Use, and Physical Planning

Source: Asian Development Bank.

(ii) Land use planning. Land use planning defines the broad uses of land in order to guide balanced, strategic, and plan-led development. A more advanced and comprehensive planning approach seeks to integrate development policies related to land with other policies and programs that also influence a city’s economic, social, and environmental fabric. These development policies might include, for example, policies that (i) maximize land-based revenues, (ii) release public land for public purposes, or (iii) promote mass affordable housing developments in mixed-use developments served by public transportation, to cite a few examples.

What is clear is that cities need plans and strategies to guide their spatial development in a manner that both manages population growth and supports the local economy. Cities that try to block growth do not typically succeed (Angel 2012) and should thus embrace and plan for it.

The different indexes consulted on city competitiveness indicate that quality of life issues matter—access to green space, a clean environment, and low commute times—and these are major features that do not just happen organically. They require deliberate land use decisions as well as strategies and the capacity to implement and enforce plans. The latter is discussed in more detail in the subsequent sections on governance.

Not all land use planning outputs have been successful in helping cities to realize their goals. There are many examples of top-down, stand-alone master plans that are too rigid or not easy to use; or for which there is little ownership and financing, perhaps because the exercise was completely outsourced with little local involvement. Emerging experiences suggest that more consultative and multidisciplinary land use plans with clear linkages to the city’s economic vision, investment plans, sector-specific plans, and operating budgets are a smarter way to go in shaping the urban form and supporting city dynamism. The newer, more flexible plans that are emerging set out principles to guide development, or identify focus zones for development linked to the economic vision (e.g., waterfront, clusters, corridors) rather than predetermining the usage of each plot. They may also restrict certain high-impact developments (e.g., industrial parks near environmentally sensitive areas) but leave room for some discretion so that cities can be more reactive to emerging demands and opportunities (Box 4).

Box 4: From City to City-Region: Helsinki Strategic Spatial Plan

Helsinki, the capital city of Finland, has a spatial strategy with a 30-year vision that is updated every 4 years. The strategy is an implementation document for the master plan, which is usually updated every 10 years. For the first time, the 2009 strategy set out guiding principles for future development that look beyond Helsinki’s boundaries to the city-region. This is in line with European Union Territorial Agenda guidelines on spatial planning.

The 4-year review process allows the City Council to decide if the strategy is still relevant for supporting city vitality and competitiveness, and if the Master Plan also requires any revisions.

Source: City of Helsinki. 2009. From City to City-Region: Strategic Spatial Plan. Available at www.hel.fi/hel2/ksv/julkaisut/julk_2009-8.pdf

(iii) Physical planning. Infrastructure is a key element of competitiveness—and a key function of government. What ultimately matters to business is the quality of services made possible through infrastructure—the quality, reliability, and cost of water, for example—rather than whether the distribution network is in place. But services are precluded by the advance efforts of planning and development of infrastructure.

Investments in infrastructure are imperative if cities are to (i) meet existing demands for basic services, (ii) keep pace with population growth, and (iii) attract business and investment. Companies have a number of factors to consider when deciding where to start or expand their operations. Key among these is the existence, quality, and cost of services from critical infrastructure. Infrastructure deficits can raise the cost of doing business and constrain productivity. Local government has a critical role to play in the provision of value-for-money services with benefits that accrue due to economies of scale. While business and individuals can, in some cases, meet their own needs (for example, for water supply through private wells), this is not efficient and not the way forward for competitive cities. The financing of infrastructure and the quality of services are critical. But adequate infrastructure and services cannot exist without proper planning.

There are basic issues related to physical and infrastructure planning that should be dealt with as a matter of good practice. These issues, which affect the sustainability of the infrastructure, include technical suitability and quality, environmental and social impact assessment, cost–benefit analysis and integration with other infrastructure, and capacity to support operation and maintenance (O&M), among others. There are institutional, financial, and strategic issues that should also be addressed at the early planning and appraisal stage, including (i) institutional clarity for developing and operating infrastructure, (ii) funding sources for O&M, and (iii) whether the priority should be to increase the focus on maintenance of existing assets before investing in new assets.

So what does infrastructure planning that goes beyond traditional infrastructure planning and supports city competitiveness look like? It should, at a minimum, (i) respond to confirmed demand, (ii) support the city’s economic vision, and (iii) have high expected economic returns. These may sound basic, but they are still too often neglected during the planning phase—or, as is often the case with large infrastructure projects worldwide, the benefits tend to be inflated and the costs tend to be underestimated.

Infrastructure plans should therefore aim to depict more realistic benefits and costs and reflect economic plans and land use plans, all geared to supporting competitiveness. This three-pronged approach (integrated economic, land use, and infrastructure planning) builds a strong foundation for the other steps in the urban development cycle—implementation, operations, enforcement, and reviewing and updating plans. Without a strong blueprint, development will be piecemeal and not at the scale and integration required to support city competitiveness. The linkages between economic planning, land use planning, and physical planning as described above help to ensure that resources are channeled to support aspects of the economy with the greatest potential to spur further economic growth, and that the urban form and infrastructure are deliberate in supporting city competitiveness.

What are the constraints on the use of the planning process to drive city competitiveness in South Asia? As cities in South Asia drive growth in the region and people are progressively concentrated in urban agglomerations, urban planning has, at least on paper, gathered importance across the region. An increasing number of institutions have been established at the national, state, provincial, and metropolitan levels to lead the process. However, urban planning has, in practice, improved little in most cities across South Asia. Most cities are practicing traditional land use planning at best—and not yet developing a more comprehensive spatial planning system based on a comprehensive city information base that links economic development objectives with land use and infrastructure planning. Staff capacity remains an issue. Despite manifestations of economic change, land use and physical planning are rarely preceded by or based on an assessment of economic drivers or proposals for economic planning at the city or metropolitan level. Planning systems tend to be closed rather than open and communicative, and guided more by power than by rational decision making. The ills are complex and involve both processes and institutions.

For starters, the public sector is not typically driving the coordination and facilitation of local economic development. There are institutions with the mandate for spatial planning and service delivery, and for macroeconomic planning (usually at the national or state level), but there is a gap in terms of cit...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Boxes, Figures, and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Why Planning, Governance, and Finance Matter for City Competitiveness

- Chapter 2: Methodology

- Chapter 3: City Competitiveness Profiles

- Chapter 4: Insights and the Way Forward

- References

- Appendix 1 – Checklist and Scores for Rating by the Expert Panel

- Appendix 2 – Local Panel Scores

- Index

- Back Cover