![]()

The Water-Food-Energy Nexus

Context

The global debate is not about water security or water scarcity in isolation. Instead, it is about the nexus, that is, the links among water, food, and energy. For instance, in Asia, the extraordinary growth of industrialization and urbanization pushes the demands for energy, but expanding power production will be limited by water availability. But it is the growing demand for food, with its high water requirement, superimposed on population growth, which crucially turns an abstract crisis into a critical and immediate one.

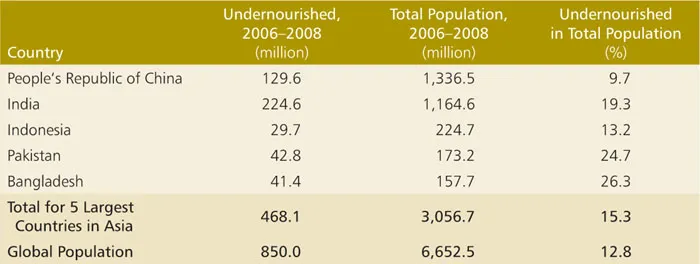

The real threat is food scarcity, the ever-present risk of food price instability and the still-existing scourge of widespread poverty in the region. Over 568 million people, or 15% of the population, remain undernourished today.6 These issues are much more visible than a future, abstract problem with water, which is largely invisible. Concerns about water security are shared globally. But Asia has its unique features in this: it has enormous opportunities, but equally some very real threats. The contrast is striking. The water crisis has been brought into this urgent focus partly because of the increasing wealth in newly industrializing PRC and India, with the resulting changes in lifestyle and consumption and aspirations of a growing urban middle class. At the same time, the Asia region (with about 58% of the world’s population) holds 67% of the total global undernourished population (Table 1).

Table 1. Population Undernourished in Asia’s Largest Countries

Source: FAO. 2011. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2011. Rome.

Decision makers and constituencies cannot be convinced of the need to act on water security if its urgency are not supported by indisputable and clearly accessible facts that show how many issues are linked and thus have similar solutions.7 The focus, therefore, must be on putting such facts and information into the public domain. Decision makers must acknowledge that

(i) | food security will only worsen unless agricultural productivity is improved and the waste in the water used for agriculture is reduced; |

(ii) | food prices will continue to be subject to fluctuation, with causes on both the demand-and supply-side, including increasing frequency of weather shocks; and |

(iii) | poverty in rural and urban Asia will only worsen if strategic groundwater reserves continue to be mined and consumed, and if aquatic ecosystems continue to be destroyed by failing to account for their real value in stabilizing and storage. |

Old water economics has failed to protect the resource. Market mechanisms have failed. Nonrenewable resources have been mined; water has been given away for free, often through blanket energy subsidies. Strategic future resources have been polluted as a cheap, convenient method of waste disposal. Such actions were possible largely because the underlying data were obscure; that is, the economics were not transparent.

Further, the competing calls on constrained water resources have become too great to permit arbitrary and unconstrained withdrawals without making rational allocations, based on agreed systems of trade-offs. In other words, what is called for is good water governance.

Water Resources

Throughout history, the development of water systems has enabled economic growth and productivity, with natural aquatic systems being transformed through changes in land use, urbanization, industrialization, large-scale agriculture, and as a convenient recipient of waste. Growth has been made possible through massive investment in water development on the supply-side—pumping, transfer, treatment, and distribution—during what has been termed “the hydraulic century.”8

However, biodiversity of aquatic systems has rarely been awarded any economic value, resulting in their often-irreversible degradation. Recent global-scale analyses of threats to freshwater have considered water security and biodiversity simultaneously within a spatial accounting framework.9 The graphic displays of river catchments under immediate threat have caught the attention of the media and contribute to an increasing concern among the public, which, in turn, may put greater pressure on global industries, international agencies, and governments to act more responsibly. The developing world—in particular, highly populated parts of Asia—show the tandem threats to human water security and biodiversity.

One of the key comparisons in the body of evidence on global water scarcity distinguishes between physical water scarcity and economic water scarcity (Box 3). Physical scarcity occurs where there is not enough water to meet demand. Usually associated with arid regions (e.g., West Asia and the Arabian Peninsula), physical scarcity can also occur when water resources are overcommitted. In such cases, remedial measures must include reducing demand, improving production efficiencies, and instituting trade measures to substitute homegrown commodities with a large water footprint. Other examples in Asia are south and northwest India, most of Pakistan, and the northern part of PRC. Economic scarcity, however, is caused by a lack of investment—and should, therefore, be a focus of possible intervention on the supply-side and improved management. Examples in Asia include Bangladesh, Cambodia, north and northeast India, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, Nepal, and Viet Nam.

Water for Food

Water for food production accounts for about 70% of water withdrawals.10 Combining increases in overall population, urbanization, and prosperity with changes in dietary demands, the demand for food will further increase considerably. For example, changing lifestyles and diets in Asia will increase demand for water-intensive products such as dairy and meat products. Estimates for the rise in the demand for meat globally cite an increase of 50% by 2025.11 In addition, the emergence of subsidized biofuels for transport has led to greater competition for land and water use. A proportional increase in water withdrawals cannot be met without major shifts in production patterns.

Globally, 80% of water for agriculture comes directly from rain, and about 20% comes from irrigation. In Asia, the proportion using irrigation is much larger, predominantly in South Asia and southern portions of the PRC.12

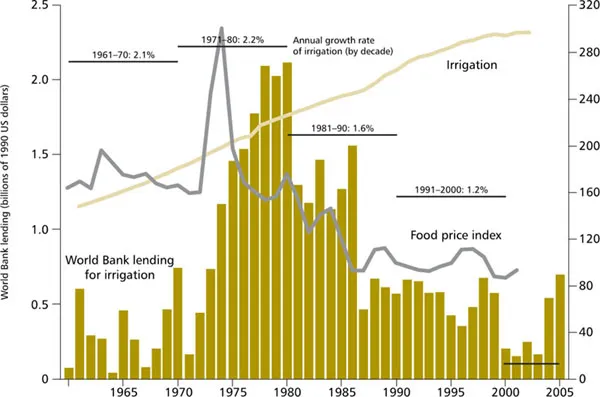

The global food price index has steadily declined since 1975 (Figure 2).13 Agricultural production has grown, backed by new crop varieties, fertilizers, investment in irrigation infrastructure, expansion of agricultural land, and subsidized access to easy-to-reach groundwater. Although world food production outstripped population growth, food price volatility reappeared in 2007/2008 and 2010/2011, possibly signaling the end of low food prices and the new prospect of long-lasting scarcity.14 This could be recognized as the end of a period of structural overproduction in international agricultural markets, made possible by the extensive use of cheap natural resources backed by farm subsidies (i.e., a reliance on an unsustainable mining of nonrenewable resources, like water). Groundwater has been abstracted beyond recharge potential, and soil and aquatic ecosystems have been loaded with waste products and residues beyond their natural absorptive and self-cleansing capacity, often causing irreversible damage. No economic or financial value was attached to the use of these nonrenewable resources that could have influenced a choice of alternatives, thereby remaining “negative externalities,” in economic terms.

Figure 2. Irrigation Expanding, Food Prices Falling

Source: Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. 2007. Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. London: Earthscan and Colombo: International Water Management Institute.

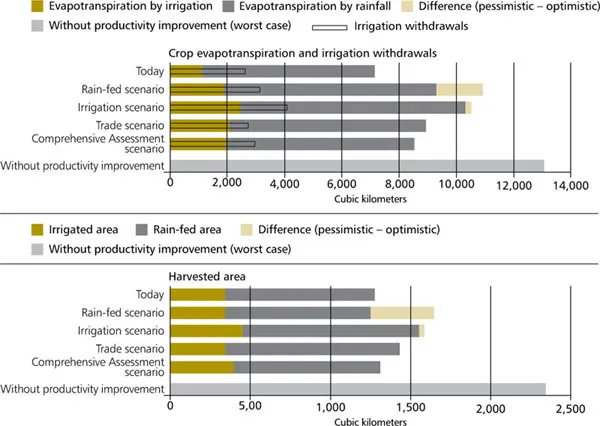

However, future food demands can be met by the world’s available land and water resources in several ways.15 Appropriate combinations of the four scenarios summarized below (and presented in Figure 3) will depend on local settings, and all will require considerable changes in policies, institutions, and skills.

Figure 3. Land and Water Use Today

Note: The figure shows projected amounts of water and land requirements under different scenarios. The Comprehensive Assessment scenario combines elements of the other approaches. The purple segments of the bars show the difference between the optimistic and pessimistic assumptions for the two rain-fed and the two irrigated scenarios. The brown bar shows the worst-case scenario of no improvement in productivity.

Source: Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. 2007. Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. London: Earthscan and Colombo: International Water Management Institute.

(i) | Rain-fed scenario. Investment to increase production in rain-fed agriculture through enhanced management of soil moisture, supplemental irrigation with small water storage, improvement of soil fertility management, and reversal of land degradation. The range displayed under this scenario reflects the uncertainty of the impact of climate change on future rainfall patterns. |

(ii) | Irrigation scenario. Investment in irrigation by increasing irrigation water supplies (e.g., through innovations in system management, new surface water storage facilities, and using wastewater) and increasing water productivity in irrigated areas and value per unit of water (this is specifically valid for South Asia, where 50% of cropped area is irrigated and where productivity is low). |

(... |