![]()

MSE Finance

Introduction

Lack of access to banking and other external sources of finance, a major obstacle to enterprise development, is a common feature of small businesses around the world. From the perspective of financial institutions, difficulties in providing financial services to small businesses are related to severe information asymmetry—a logical starting point for theoretical research and policy discussions on small-enterprise financing.

A great deal of effort has been made by the national government, donors, and researchers to overcome problems with small-enterprise financing. Yuan and Cai (2010) argue that the causes differ between countries and over time, and the policy solutions should as well. Yin and Weng (2007) note that bank mergers and acquisitions, and the consequently higher bank concentration rate in the Western economies since the 1980s, have had a negative impact on small-enterprise financing. In the PRC, the research has so far focused on bank size: whether small and medium-size banks are more likely to provide financial services to MSEs.

Improving the access of small enterprises to financial services is beneficial not only to the national economy and small enterprises, but also to the lenders. Research shows that as small businesses develop, the economy flourishes and employment grows, income distribution improves, and poverty is reduced (Yuan and Cai 2010). Access to financial services for small businesses has, however, been discriminatory, despite the fact that supporting small enterprises could diversify and improve the lenders’ loan portfolio and thus lower their loan concentration rate, lessen their risk exposure, and strengthen their core competitiveness. Liu (2005) points out that increasing small business lending would lead not only to a lower loan concentration rate for the lenders through a more diversified loan portfolio, but also to innovations in risk management techniques and system, and enhanced risk management capacities.

There is information asymmetry between small businesses and banks in the credit market. In particular, (1) small enterprises generally do not have standardized and accurate financial statements; (2) it is difficult to measure credit risk of small enterprises, especially those with short operating history, because there is no accumulation of historical data and reliable external credit rating; (3) uncertainty from frequent and significant business fluctuations (Zhou, 2006); and (4) small enterprises have less fixed assets, and usually of low value. On the other hand, special requirements on information may also hinder information transmission (He & Rao, 2008). Information required by most commercial banks is “hard information”, while information on operations generated by SMEs mainly take the form of “soft information”. Information asymmetry may also occur if soft information is not communicated accurately, which is obviously related to the misguided notion that there is no cost advantage of collecting and processing such information.

Financial innovations are the key to small-enterprise financing. In the 1990s, some international institutions, including the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, started to improve the lending models and procedures for small enterprises. They showed that small-enterprise financing could be profitable if the lenders were to ensure that their products are responsive to the needs of small enterprises, set interest rates according to market conditions, focus on loan repayment capacity when assessing loans, simplify lending procedures, and provide good incentives to their loan officers (Liu 2005). Wells Fargo introduced credit scoring to small-enterprise lending and designed the first-generation credit scorecards. Wells Fargo ranked first in small-enterprise lending in the US in 2004 and maintained the ranking for 3 consecutive years, reaching 15% of the American market, with a lower bad-debt ratio than initially expected (Jiang 2006).

The government has adopted several policy measures in an effort to deal with the problems that beset small-enterprise lending. The Small and Medium Enterprise Supporting Act passed in 2002 called on commercial banks to devote a higher proportion of their loan portfolio to SME lending. The PBC has also repeatedly lowered its basic lending rates for small-enterprise lending. In April 2005, a joint international workshop on MSE lending was held in Beijing, with the support of the PBC, the CBRC, and the World Bank. That same month, the CBRC issued “A Guideline for Commercial Banks to Undertake Small Enterprise Lending,” which encouraged commercial banks to establish small-enterprise lending operations with risk pricing, independent accounting, specified loan assessment and approval procedures and incentives, and training programs tailored to the character of MSEs. The market mechanism and commercial principles were emphasized in the guideline, to prevent moral hazard problems with commercial banks in the PRC.

The CBRC released the “Guidelines for Banks to Establish Small Enterprise Service Department (Centers) Specializing in Servicing Small Enterprise” in 2008. In 2011, the CBRC issued “An Announcement for Commercial Banks Further Improving Financial Services for Small Enterprises,” which discounted small-enterprise loans in the calculation of a bank’s total loans (the CBRC set loan deposit ratios for commercial banks to control total lending), as well as risk-weighted assets in the determination of the capital adequacy requirement, to reduce the pressure on commercial banks to meet the equity requirement.

China Development Bank (CDB) has pioneered in small-enterprise lending in the PRC and invested large amounts of capital, technology, and manpower. In 2004 and 2005, the CDB and the World Bank launched a microfinance downscaling project in which participating commercial banks received technical support and wholesale loans. International Project Consulting (IPC), a German consulting firm, was selected as technical assistance (TA) adviser. In the IPC microfinance model, the loan assessment method depends much less on physical collateral, thereby easing difficulties in small-enterprise lending. Following the example set by the project, many rural and city commercial banks started their own MSE lending experiments. Even the ‘Big Four’ banks (BOC, China Construction Bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and ABC) and joint-stock banks formed special small-enterprise loan departments or centers, and a number of commercial banks decentralized, to varying degrees, the decision-making authority for small-enterprise lending.

There have been many studies on small-enterprise lending in the PRC, among them: “A Review on Small Enterprise Financing Theory and Empirical Evidence” (Tian 2004), “Comments on Relationship Lending and Small Banks’ Advantages” (Yin and Weng 2007), “Research on Progress in Relationship Lending” (Li 2009), and “Research Review of Small Business Financing Policy” (Yuan and Cai 2010b). This chapter is focused more on relationship lending in the PRC context and includes the results of econometric research and case studies. Relationship lending is the starting point for studies on small-enterprise lending. Unlike large enterprises, small enterprises generate mainly the soft information on which relationship lending is based. In view of technological advances and the hardening of soft data, the importance of relationship lending in explaining small-enterprise lending should be reconsidered.

The spotlight here is on MSEs because difficulties in gaining access to finance mainly affect them, especially MSEs with a short operating history. According to Li and Yang (2001), the loan rejection rate declines with the length of time an enterprise has been in operation and as the enterprise grows in size. For instance, a firm with fewer than 500 employees is three times more likely to have its loan application rejected than a firm that employs 500 or more. On the supply side, this chapter concerns itself mainly with bank loans, as no other formal channels of finance are available to a large majority of unlisted small firms (He 2010).

In the rest of this chapter, MSEs are defined and the current state of MSE financing, based on survey results, is documented; the reasons behind the difficulties in MSE financing are summarized; the literature on relationship lending, with a focus on information, credit technique, and organization, is reviewed; the latest IPC Model and the Credit Factory Model are examined; and, finally, conclusions are made.

Micro and Small Enterprise Financing in the PRC

Definitions

Before the problems of small-enterprise lending can be dealt with, medium, small, and microenterprises must first be defined (Wang 2007). Small enterprises must also be distinguished from the rest of the enterprises in the “SME” category (Yuan and Cai 2010b). Indicators such as number of employees, total assets, and annual sales are commonly used to define micro, small, and medium enterprises. Table 5 lists the criteria used by the World Bank. In the PRC, the revised “Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Classification Standards (2011)” classify as “small” those enterprises with 20 or more employees or at least RMB3 million in annual operating income, and as “micro” those enterprises that employ fewer people or have less annual operating income. The CBRC defines small enterprises as independent entities with a credit line of up to RMB5 million, and total assets of up to RMB10 million or annual sales of up to RMB30 million. In practice, however, commercial banks treat loans of RMB1–RMB5 million as small business loans, and loans below that range as microenterprise loans (or microloans).

Table 5. The Classification of Enterprises in the PRC by Industry

Notes: 1. Number of Employees.

Source: The Ministry of Industrial and Information Technology, Document 300, 2011.

The research conducted by the PRC’s National Bureau of Industrial and Commercial Administration (BICA) in 2014 show that by the end of 2013, of 15.3 million registered enterprises in the PRC, 76% were small and micro enterprises, based on the classification of enterprises in the PRC. In addition, there were an additional 44.4 million registered individual industrial and commercial households, these households are de facta microentrepreneurs. In other words, in terms of number of enterprises, MSEs accounted for 94% of all enterprises in the PRC. The same study indicates that SMEs have contributed to over 60% of GDP growth and over 50% of the tax incomes in the PRC whilst MSEs provided jobs for 150 million labourers in the PRC. The statistics above are based on the classification of the enterprises in the PRC presented in Table 5.

Table 6. World Bank Definition of Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

Source: Wang (2007).

Following Yuan and Cai (2010b), this study refers to small and medium-sized enterprises as “SMEs,” and micro and small enterprises as “MSEs.”

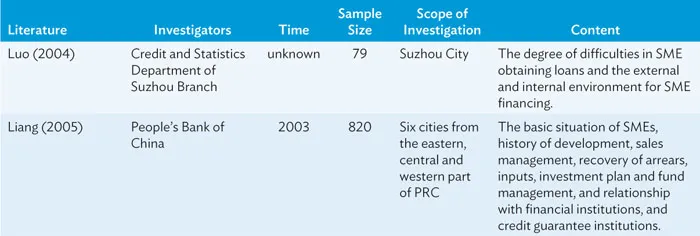

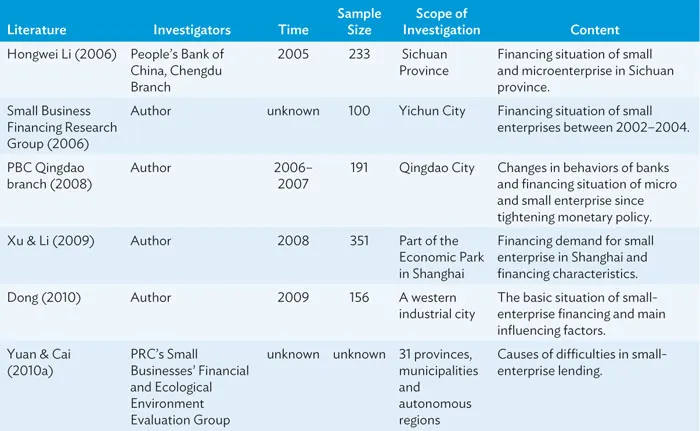

Given the lack of statistical data on SME financing in the PRC, classified according to firm size and loan amount, this study uses data and information from ad hoc field surveys. The results of some key surveys on credit demand, credit channels, loan access, lending methods and credit guarantees for small enterprises are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7. A Summary of Surveys on Credit Demand, Channels and Loan Conditions

Types of MSE Loans

Working-capital loans are most in demand among MSEs. Li (2006) reports a large gap between demand for formal loans and credit supply, according to two-thirds of a sample of 233 randomly selected MSEs from 21 prefectures in Sichuan province. Most of these businesses look for small, short-term loans, with quick and easy access.

Another survey of small enterprises, this time in Shanghai, indicates that small enterprises borrow mainly for working capital (42% of the 351 enterprises in the sample) and market development (34%) (Xu and Li 2009). The rest borrow to finance technology upgrades (14%), to repay bank loans or settle unpaid wages (9%), or to fund capital investments (2%).

MSE Financing Channels

Enterprises have two broad channels for their financing: internal and external channels. Internal channels of financing are equity finance, allowable depreciation on capital goods, retained earnings, and borrowings from employees. External channels, on the other hand, can be divided into direct financing (raising funds through the stock market) and indirect financing (borrowing from financial intermediaries like banks and nonbank financial institutions).

Most small enterprises in the PRC engage in labor-intensive industries with relatively simple technology and stable market conditions (Liang 2005). The nature of these enterprises helps to shape their channels of finance: internal finance and indirect financing (Lin 2003). Th...