![]()

CHAPTER 1

Revolution on the Margins

Northern Korea and the Manchurian Experience

In order to understand how communism was subsequently implemented in North Korea, it is important to recognize some of the distinctive features of northern Korea and the Sino-Korean border region before 1945. Communism, of course, took hold north of the 38th parallel during the 1945-48 Soviet occupation, and the distinctive nature of the northern region influenced the development of communist society in the North thereafter. Although the leadership of North Korea included people with diverse geographical backgrounds and experiences in Korea itself (including a substantial southern contingent), China, Japan, and the USSR, it was ultimately the group associated with Kim Il Sung and the anti-Japanese struggle in Manchuria who came to dominate North Korean politics. Thus the vision of socialism shaped in exile in Manchuria profoundly influenced the development of the North Korean state.

The northern part of the peninsula had been an economically, politically, and socially marginal part of Korea for centuries. Economically, because of its rugged terrain and short growing season, the mountainous north played a much smaller role in Korea’s agricultural production than the plains of southern Korea, especially when compared to the “rice basket” of the Chŏlla region in the southwest.1 Politically, residents of the northern provinces (P’yŏng’an and Hamgyŏng) had been virtually excluded from higher office in the state bureaucracy through most of the Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1910). Only at the end of the nineteenth century did the number of higher examination passers from the north approach their proportion of the overall population, and among the successful northern examination candidates most were from P’yŏng’an province; the northeastern Hamgyŏng region continued to be politically marginalized.2 Socially, northerners had long suffered a reputation for unruliness, violence, and independence. The Japanese colonial authorities, like their Chosŏn predecessors, had found the northeast of Korea the most difficult area to bring under control.3

The Hamgyŏng region was particularly unusual in its social structure. Tenancy rates in the north were generally lower than in the south, but only in North Hamgyŏng province were more than 50 percent of the peasants owner-cultivators. The province with the second-highest ratio of owner-cultivators (32 percent) was South Hamgyŏng.4 Mutual aid associations (kye) were more prominent in the northeast than in other part of Korea.5 P’yŏng’an and Hamgyŏng were both caught up in radical thought and politics in the first half of the twentieth century, but in different ways. In P’yŏng’an, both nationalist and peasant protest movements were often associated with religion. Pyongyang, the largest city in northern Korea and capital of South P’yŏng’an Province, had been the center of Korean Protestant Christianity since the beginning of the twentieth century. Pyongyang missionary schools became important centers of modern education, and by the end of the colonial period many of the prominent Korean nationalists in the P’yŏng’an region were Protestant Christians, including Presbyterian elder Cho Mansik, who headed the South P’yŏng’an People’s Committee in August 1945 and was the leading nationalist figure in North Korea in the months following liberation.6

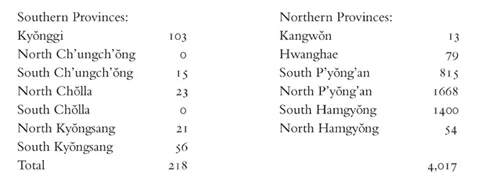

By the 1940s, Christianity in northern Korea (as in the South) tended to be an urban and middle-class phenomenon. In the P’yŏng’an countryside, organized peasant protest was predominantly led by the Korean Peasant Society (Chosŏn nongminsa) affiliated with Ch’ŏndogyo, a religion whose roots lay in the great Tonghak peasant uprising that nearly toppled the Chosŏn dynasty and triggered the Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95.7 After the Tonghak rebellion was crushed in 1895, many Tonghak believers moved north. By the early twentieth century the geographical center of Tonghak—renamed Ch’ŏndogyo in 1905—was the P’yŏng’an area.8 In 1923 Ch’ŏndogyo believers formed a “Young Friends’ Party” (Ch’ŏng’udang) as the political wing of the religious organization. The provincial distribution of the Ch’ŏndogyo Young Friends’ Party shows a striking concentration in the north:9

Given the prominence of Protestant Christianity and Ch’ŏndogyo in P’yŏng’an-area nationalist and peasant-populist politics during the colonial period, it is not surprising that the two main rivals to the communists in the post-1945 North Korean regime—based in the city of Pyongyang—were the Christian-led Korean Democratic Party (Chosŏn minjudang) under Cho Mansik, and the Ch’ŏndogyo Young Friends’ Party. This three-cornered struggle will be discussed in chapter 4.

“New religions” such as Protestant Christianity and Ch’ŏndogyo played less of a role in radical activity in Hamgyŏng. There groups associated with the socialist left, especially the so-called “Red Peasant Unions” (Chŏksaek nongmin chohap) of the 1930s most often took the lead in protest against the colonial authorities and in expressing peasant grievances.10 The Korean socialists and communists looked at Ch’ŏndogyo and the Korean Peasant Society with suspicion, considering the latter “reformist” rather than revolutionary. Ch’ŏndogyo and the Korean Peasant Society only agreed to cooperate with the left against the Japanese in the late 1930s.11

As Gi-wook Shin convincingly argues, the rank-and-file membership joined the Red Peasant Union (RPU) movement for reasons of immediate interest rather than the abstract economic and nationalist, much less internationalist, goals that left-wing intellectuals espoused.12 Educated young peasants, often associated with left-wing political organizations and with groups and individuals across the border in northeast China, took the leading role in the RPUs. Although the RPU leaders often had no more than a few years of elementary school education,13 the RPUs were particularly active in education, organizing night schools and “reading circles” in farming villages, raising the political consciousness of the local peasants, and directing their protests against the police and local government authorities.

RPUs were concentrated in the part of Korea that had the lowest rates of tenancy and the highest proportion of independent farmers.14 As Eric Wolf observed in his classic study of peasant rebellion, it is not the most destitute peasants with “nothing to lose” who are most likely to rebel, but rather the conservative middle peasantry, “located in peripheral areas beyond the control of the central power,” who are prone to radical action under circumstances of sudden change and dislocation.15 Like North China, northern Korea was a place where the “instability and insecurity of rural life . . . despite a low incidence of tenancy, made the peasants more receptive to revolutionary mobilization.”16

This receptivity to radical mobilization is also related to the weakness of colonial state control in the region, which opened a space for rebellion in the northeast, while potential rebellion in the south was effectively crushed by the Japanese authorities. It is probably also the case that the existence of a strong social network, the lack of complete dependence on landlords for survival, and a tradition of resistance to interference from the central state gave peasants in Hamgyŏng the capacity and willingness to engage in radical protest in the late 1920s and early 1930s, at the same time that radicalism in the southern countryside declined. The very “traditionalism” of the northeastern countryside helped make it the center of peasant radicalism in the latter part of the colonial period, when the colonial state impinged on this region.

Hamgyŏng, as it turns out, was also the site of much of northern Korea’s emerging industrial base by the late 1930s, particularly in the cities of Hamhŭng and Wŏnsan, both in South Hamgyŏng Province. Thus, the northeast was both the site of populist peasant mobilization as well as more orthodox Leninist, urban agitation under communist leaders such as future DPRK Labor Minister O Kisŏp, who was based in South Hamgyŏng. The Hamgyŏng area in Korea’s northeast was the center of peasant and labor radicalism in the late colonial period, and after a hiatus between 1937 and 1945 became the most active area of radical organization in North Korea immediately following liberation. By the late 1920s and early 1930s the Japanese authorities believed that the northeast was the “front line” of communist activity, and the Korean communists themselves tended to share this view.17 This was both because of the conditions within the region, including the benefit of distance from colonial control, as well as the region’s contact with radical individuals and groups across the border in northeast China.

After the tightening of colonial control in the late 1920s, active anti-Japanese resistance among Koreans became, for the most part, an exile movement with centers in Northeast China (Manchuria), China proper, the Soviet Union, and the United States. However, the one area of some continuity and contiguity in anti-Japanese armed resistance was the remote, rugged, politically ambiguous Sino-Korean border region in the far northeast. The postliberation leaders of the DPRK have attributed tremendous historical significance to the anti-Japanese armed struggle in this area, and however exaggerated may be their claims of military success or Korean autonomy (as will be discussed below), it is undeniable that the guerrilla struggle in this region was the formative experience for those who ultimately came to power in North Korea, and as such profoundly influenced the new political and social system created in the North.

The Sino-Korean border region had been an area of exile, escape, and experimentation since the late nineteenth century. A general decline in rural living standards throughout the nineteenth century had already disrupted Korean peasant society by the time the Japanese took over.18 One consequence of poverty and social dislocation was frequent peasant rebellion, culminating in the Tonghak uprising of 1894, the largest peasant protest in Korean history.19 Another response to social dislocation and impoverishment was a marked increase in vagrancy and migration.20 Many poorer peasants were forced into the mountains to attempt ...