During my fieldwork in Uyanga, such voiced frustrations occurred quite often in the large herding households located in the vicinity of the mines, especially when daily tasks took us far away from the compounds. Ahaa’s situation was particularly difficult. His father was one of the wealthiest and oldest herders in the area and immediate respect was expected to accompany his movements within and beyond the ail. While he was respected for being a nice and generous man, he was also single-handedly in charge of all final matters relating to the ail and its herd. Indeed, Yagaanövgön was a strong-minded man who enjoyed a good discussion that preferably confirmed that he was right. Although the village and the mines were located only thirty minutes away by motorbike or an hour by horse, they seemed very far away. The family’s nearest neighbor lived on the other side of the mountains, and they sometimes went many days without seeing any visitors (see figure 5). In particular the eight months-long winter entailed a remarkable degree of isolation in which they drew their daily entertainment almost exclusively from one another’s company. At such times, the elderly man could be seen walking alone behind his herd, bow-legged, leaning slightly forward into the wind and with his hands clasped behind his back. Or he sat in the honored northern part of the ger, lighting a “butter candle” (zul) on the altar before launching into a lengthy monologue about matters he considered urgent or simply interesting. At times he talked about the kind of medical treatment he thought necessary for his wife, who was suffering unbearable kidney pain. At others, he described the kind of tea he wanted his sons to buy upon their next visit to the village.

As he spoke, family members occasionally mumbled their discontent with his decisions. Given his poor hearing, it was likely that he did not notice their objections. Or perhaps he simply did not care. But when he did hear, he looked sternly at the person in question and exclaimed a forceful “What?!” (yüü). Regardless of the response, he mumbled exhaustedly, as if to himself, “Oh, how difficult this is! Even my own family doesn’t listen to me! What to do … [Üü, yamar hetsüü baina daa! Manaihan l nadad toohgüi! Yüü hiih ve…].” More often than not, the other member eventually grew quiet, and the elderly man continued his speech. But as soon as an opportunity arose to momentarily leave the ail, household members would often vent their exasperation.

Before carrying out my fieldwork in Uyanga, I had presumed that ninja mining would come up most intensely in contexts that related to the obvious environmental clash between the country’s two largest economic sectors: herding and mining. With thousands of ninjas panning for gold, rivers were turned into stagnant mud, leaving herders with no drinking water for themselves and their animals. As fertile pastureland was perforated with deep mining holes, connected underground with unsupported tunnels, the mines were unlikely to ever again become safe for human and animal habitation. These environmental disasters have indeed happened, and herders often lamented the seemingly gloomy future ahead of them. This reality struck during the winter of 2005–6 when herding households ran out of drinking water. Since my hosts lived upstream from the mines, their water was not polluted with heavy metals and sediments from panning, but waves of ninjas had begun prospecting at the headwaters of previously untouched streams that fed into the region. When the nearby spring one day dried out, people were entirely dependent on the intermittent snowfall. Bags were filled with snow and stored indoors until needed. Men equipped with axes and saws broke loose large chunks of ice that were transported back on horseback. When precipitation stopped in late February and there was no more snow or ice to collect, desperation took over and many households in the area began to move. In this situation my hosts furiously blamed the nearby mining for their feared predicament. However, in daily life such dramatic conflicts were rare, and complaints about the environmental consequences of mining were usually incorporated into much more casual conversations about the general difficulties of the herding life. Even if it was the environmental clash that struck me, these contexts did not spark the most frequent allusions to mining among people living on the steppe.

This chapter introduces the many herders who have been drawn to the mines. Apart from those who have lost their livestock in weather disasters (zud), I consider why members of wealthy herding households have also decided to follow gold (alt dagah). Rather than attributing the rush to a historical exodus away from nomadic pastoralism or poverty, the chapter shows how the search for gold is a pressing reality in daily life on the steppe, intersecting with and feeding off some people’s desires for an alternative way of life.

A Gold Rush in Uyanga

According to official records, gold was first discovered in Uyanga in 1940, and in almost every subsequent decade further geological surveys were carried out by Soviet geologists (see Erel Kompani 1994). Davgaa and Zayat, an elderly couple, vividly remembered the geologists’ visits: “The Russians came here a long time ago and took photographs. They brought all kinds of strange [hachin] equipment with them and walked up and down the valley. They stayed in their own tent and didn’t come to visit us. But they kept coming back many, many times.”

The Soviet geologists never built a mine in Uyanga, but they carried out all the preparatory work, which they filed in the GeoFund, the once-secret national archive for geological data in Ulaanbaatar. Decades later, when the archive was opened to the public, the Soviet reports were accessed by the Mongolian mining company Erel, which soon became the largest in the country from the fortune it made in Uyanga.

Whereas much of Mongolia’s gold is found in hard-rock formations that require considerable time and effort for its extraction (Murray and Grayson 2003, 45–48, Grayson 2006), Uyanga’s gold is found in placer deposits.2 These are “deposits which originated elsewhere and at a later stage ended up ‘placed’ in their locations, mainly by movement of water, but also by movement of wind and sand. Since they are relatively younger than their matrix, they are not geologically integrated with it and hence relatively easy to extract” (Stemmet 1996, 8).

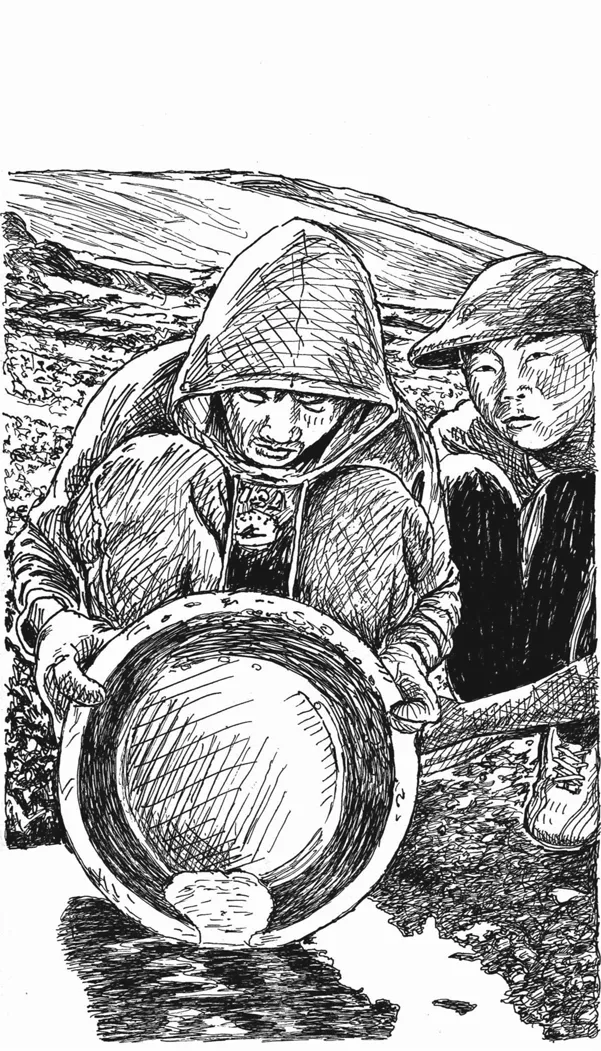

This particular geological formation of gold requires only minimal technology for its extraction yet provides a relatively high yield. Given its accessibility, placer gold has been mined since ancient times and has been pivotal to many of the world’s historical gold rushes. The simplest way to extract placer gold is by panning (see figure 6). A handful of mined ore is placed in a panning bowl and swirled in water so that the lighter material, known in Mongolian as shalaam, is washed over the side and the heavier gold flakes settle on the bottom. In Uyanga, panning is often used in conjunction with other mining techniques such as sluice boxes (pünkyör) and water cannons (usan buu). Sluice boxes are long, open-ended, often handmade metal cases. The bottom is lined with indented rubber mats (erzeen, also known as ryezin), and as the mined ore is shoveled into the slanting sluice box together with water, the ore washes through the box and the heavier particles lodge in the mats. Sluice boxes are often combined with drums (also known as trommels) or rockers (pajur) that, together with water, effectively sift the mined ore through holes in the side, allowing only the finer particles to enter the sluice boxes. All these mining techniques rely on the central use of water and, with the exception of panning, have all been used in Uyanga’s large-scale hydraulic mining operations, which began immediately after the collapse of the socialist regime.

In 1990 Erel received government approval to begin mining only a few kilometers from the village in the area where the Soviet geologists had years before located large placer deposits (Erel Kompani 1994, 21). Mining exploration started in 1993 on the placer that runs through the valley adjacent to the Ongi River (see figure 1 in the introduction). At that time, the Ongi River was among the longest rivers in Mongolia, flowing from its source in the Hangai Mountains of Uyanga into the large lake of Ulaan Nuur in the South Gobi province. Diverting and setting up dams on tributaries to the Ongi River, Erel used the river water to feed its high-pressure water jets. The water jets were directed at the gold-bearing deposits, and the resulting watery sediment slurry flowed through large sluice boxes. Once the slurry had been processed, tall heaps of waste tailings were leftbehind. As with any hydraulic mining, Erel in effect washed out the entire valley and its hillsides to get to the underlying deposits, sweeping tons of debris into nearby streams and rivers.3 Over time the debris settled, contributing to today’s heavy mineral and sedimentation pollution of the Ongi River (Tungalag, Tsolmon, and Bayartungalag 2008; see also Lovgren 2008). Now nicknamed the Red River (Ulaan Gol) because of its changed color, the river runs for less than one hundred kilometers before drying up (see chapter 2 for a discussion of attempts to protect the Ongi River). As the mining company slowly worked its way up the valley, ninjas soon moved in and started panning the waste tailings for leftover gold.4

The Mongolian gold rush appears to have started around 1995–96 in several different areas, one of which was Uyanga (MBDA 2003, 25). That these areas are far apart likely reflects people’s general desperation and creativity at a time of severe societal turmoil. State-owned mining companies had closed, and many miners suddenly found themselves without jobs. The GeoFund archive had just opened its doors to the public, and, as geologist Robin Grayson (2007, 3) notes, “The Soviet GeoFund enabled the placer gold rush to be a fast, precise, profitable mining rush; not a slow, speculative exploration rush, for the Soviets had proved a vast resource of ready-to-mine placer gold in more than two decades of churn drilling, bucket drilling and pitting.”

Figure 6. Children panning for gold. Credit: Jos Sances, Alliance Graphics.

In these turbulent transition years, many unemployed miners had the experience and technical knowledge to transfer hydraulic mining methods to small-scale, low-investment, artisanal mining operations. They also had ready access to shelves upon shelves of detailed mineral investigations, detailing the exact location and expected size of profitable deposits. As a report outlines, “Faced with a very uncertain future, a few thousand mining specialists chose to become informal gold miners, doing what seemed natural to them” (MBDA 2003, 25). This first wave of gold rush miners was then followed by people with diverse backgrounds from all parts of the country. In the words of Dorj, an elderly villager in Uyanga, “Suddenly people started coming. They came from all sorts of places, like Gobi-Altai, Bayanhongor, Hentii, Dornod, Arhangai, and elsewhere.5 One hundred people came, maybe two hundred, or three hundred. They came with their gers and everything. We were invaded by outsiders [gadny ulsuud].”

A young female shopkeeper with whom I worked closely described the early gold rush years as a time when “almost the whole nation seemed to gather around here to dig holes.” In Uyanga herders constituted the largest source of ninjas and many of them were from the local region of Övörhangai (see also MBDA 2003, 26). Around 1999–2000, when 36 percent of the population was officially recorded as living below the poverty line of 17 USD per person per month (National Statistics Office and United Nations Development Programme 1999), ninja mining in Uyanga was locally described as an altny hiirhel (gold rush). By then, thousands of people were mining for gold in the same valley as Erel.6

As the amount of gold in the waste tailings of the lower valley began to decrease, ninjas slowly followed the direction of the company’s operations and made their way farther up the placer. However, when they encroached on Erel’s licensed territory, many were evicted by armed security guards and local police.7 Throughout my fieldwork in Uyanga, ninjas continued to mine for gold on Ölt, which was desired for its relatively high concentration of gold and at its peak hosted approximately seven thousand ninjas. Since the deposits in some areas ran at a depth of sixteen to eighteen meters below the surface, it was grueling work to dig the deep mining shafts using only handmade tools such as small metal picks (skov) and hammers (zeetüü). As Odgerel, a forty-year-old herder, who had arrived in the mines in 2001, commented despairingly, “Before you dig the hole, you don’t know whether or not there will be any gold at all. There might be nothing.”

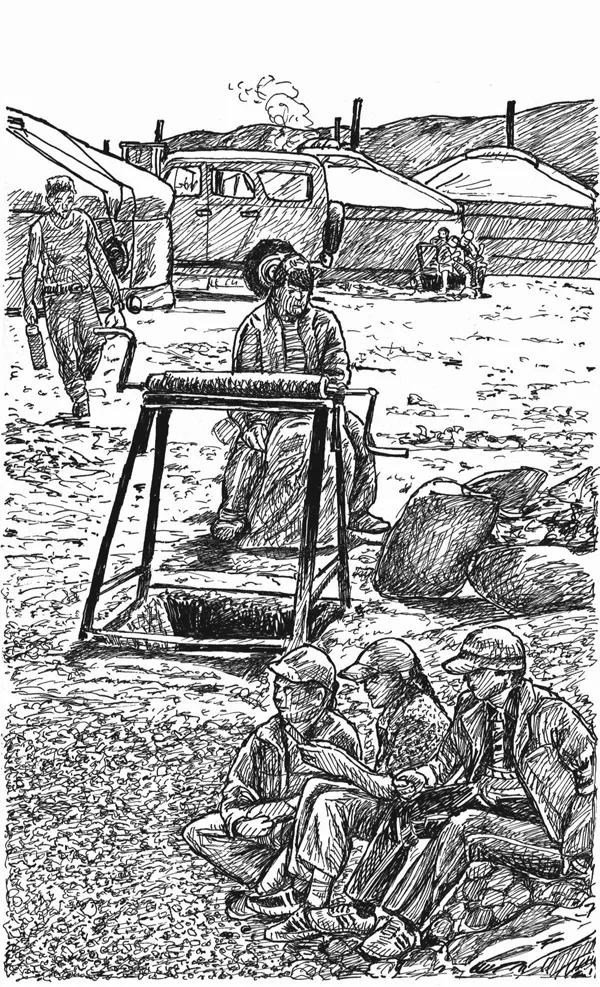

Once the mining shaft (nüh, lit. hole or opening) revealed growing concentrations of gold, ninjas branched out and dug horizontal tunnels (tünel) following the deposit. They removed the mined deposit and all the unwanted dirt (known as “overburden,” nabor) from inside the tunnels, often in buckets and bags that were hauled to the surface by means of a simple hand pulley (libotok) (see figure 7). The pulley was operated by two people working on the ground above. Since mining shafts and tunnels were not reinforced, there was a high risk of collapsing mines and landslides. Many ninjas therefore moved into the neighboring valley called Shar Suvag (lit. Yellow Vein), hosting approximately one thousand ninjas in the summer. This placer had a lower concentration of gold, but the buried deposits were much shallower, running at a depth of only about six meters. During the long winter, when temperatures dropped below minus forty degrees Celsius and mining became nearly impossible, the remaining ninjas gathered in Shar Suvag. In order to soften the frozen ground, they set fire to dried yak dung and rubber tires, which burned slowly inside mining holes. They used blowtorches to melt the ice and to keep the water from freezing, techniques that were relatively costly, time-consuming, and detrimental to both the environment and the ninjas’ health. Although most people joined the gold rush in the warmer summer months, mining thus continued incessantly throughout the year.

Figure 7. Ninjas relaxing by a mining hole and waiting to haul more bags to the surface. Credit: Jos Sances, Alliance Graphics.