Chapter 1

Thwarted Ambitions

Hollywood and Japan before the Second World War

For the October 1, 1932, issue of Kokusai eiga shinbun, a leading periodical of the film trade, Sahara Kenji contributed an essay titled “An International Aspect of the Mission of the Movies” (“Eiga shimei no kokusaiteki ichimen”). In the two-page opinion piece, the head of the International Travel Bureau of the Ministry of Railroads expressed his astonishment with cinema’s “international ability to influence” (kokusaiteki kankaryoku). Sahara’s best example was Hollywood. He noted that American cinema was a “spearhead of trade” as well as a force of “Americanization” in Japan. To him, Hollywood’s cultural power was partly evident in “gang” activities seemingly inspired by crime films, but more astonishingly in “every single movement” of the “modern boy and modern girl strolling on the Ginza,” including their “fashion or makeup.” The government official made particular note of the “kissing” of couples on the platforms of the railroad station in Tokyo. Such public actions were “utterly astonishing,” he wrote.1

Sahara’s commentary was a response to Hollywood’s growing presence in Japan. During the late 1910s and 1920s, a time when American movies began to captivate audiences around the world, U.S. studios established distribution offices in Japan to extend their business across the Pacific. Relying on its “scientifically” organized mode of business, its diverse lineup of films, and its formidable cultural appeal, Hollywood built its patronage around large urban centers where American and Western culture enjoyed wide attention. Throughout much of the interwar era, Hollywood drew many educated and well-to-do consumers who looked on the United States as an emblem of “modern” and “advanced” life.

However, the tidal wave of American movies was at best a limited phenomenon. During the 1920s, Japanese studios contested the “Hollywood menace” by gearing up their own filmmaking. By adjusting their growing business to the changing demands of the marketplace, Japanese moviemakers solidified their command over the trade. This industrial momentum coincided with a surge of policy constraints. During an era of rapid imperial expansion in Asia, the Japanese government regulated the U.S. film business through fiscal and cultural protectionism. As a result, Hollywood’s market share declined in the late 1930s until Pearl Harbor shut the doors of the film trade in 1941.

Hollywood’s prewar campaign was a sobering experience. As soon as they launched their operations, U.S. companies discovered that Japan had developed a thriving movie culture in which Hollywood cinema could achieve a large and permanent following. Yet local conditions refused to reward this optimism. A pair of obstacles — the Japanese film industry and the Japanese government — effectively undercut Hollywood’s operation. Despite much success elsewhere, U.S. film industry’s business methods during the interwar era were not good enough to win the Japanese market. American studios would have to await a second chance to test their abilities.

The Rise of Global Hollywood

The United States at the turn of the twentieth century was a nation of rising expectations. In the robust decades following the Civil War, the once-torn republic began to develop a powerful industrialized economy. As big businesses fiercely competed in a fluctuating marketplace, tens of thousands of working people from other countries arrived on American shores, yearning for success in a “land of opportunity.” As they welcomed the population influx, cities across the country were transformed into networks of railroads, telephone and telegraph poles, and electric lines. In this era of dynamic change, the United States emerged as a true global power. During the Spanish-American War of 1898, the U.S. Navy, to the world’s surprise, crushed the waning Spanish fleet in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Two decades later, U.S. forces led the Allies to a decisive victory over the Central Powers in Europe. By the end of the First World War, the nation possessed the power to influence the lives and affairs of people far beyond the shores of North America.2

Hollywood was a child of this rising nation. Born in the mid-1890s, cinematic entertainment in the United States developed first as a pastime for the expanding working-class and immigrant patrons in the industrializing cities. The dominant cinemas at the time were European, most notably Pathé Cinematograph, a French company that had managed to gain a head start in the international competition.3 Yet U.S. companies, led by the Edison Company and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, soon began to win a larger following in the domestic market.4 During the 1910s, American filmmakers developed multireel feature-length narratives with complex plotlines. Filmic storytelling increasingly relied on continuity editing, predictability, and verisimilitude acting. Distributors began to merge their businesses to extend their grip across the nation. Thanks to these developments, U.S. companies were able to recover the domestic market from their European rivals by 1917.5

Hollywood’s globalization occurred in tandem with its control of the domestic market. The main catalyst was the First World War. The destruction of Europe resulted in plummeting industrial and commercial capabilities, including the output of cinematic entertainment. Not only did this undercut the European companies’ influence in the United States, it also enabled U.S. filmmakers to extend their business across the Atlantic. Emboldened by a booming national economy, American companies began to overcome their dependency on foreign intermediaries by spreading their products through their own distribution offices. By the end of the war, American firms had established direct representation in Great Britain and Continental Europe, in addition to South America, Australia, and various parts of Asia.6 In a country that now reigned as the largest creditor nation of the world, Hollywood was set to gain command of the international film market.

The interwar decades were good times for Hollywood. At home, U.S. studios reinforced their dominance through industrial consolidation and expansive marketing. In the late 1910s and 1920s, U.S. companies vertically integrated their operations to develop a firm grip over the three branches of the business: film production, distribution, and exhibition. This institutional alignment allowed studios to streamline the creation and circulation of narrative products — from Ben-Hur (1925), It (1927), and The Gaucho (1928) to Tarzan, the Ape Man (1932).7 The industry was also able to generate extensive publicity. Aiming to excite consumers with what studio mogul Carl Laemmle once called a “circus method of exploitation,” U.S. companies showered consumers with a dizzying array of posters, photos, billboards, parades, premieres, and other eye-catching publicity.8 Exhibitors mushroomed across the nation. Many downtown theaters turned into opulent “movie palaces” that boasted cutting-edge engineering, interior grandeur, and elegant design.9

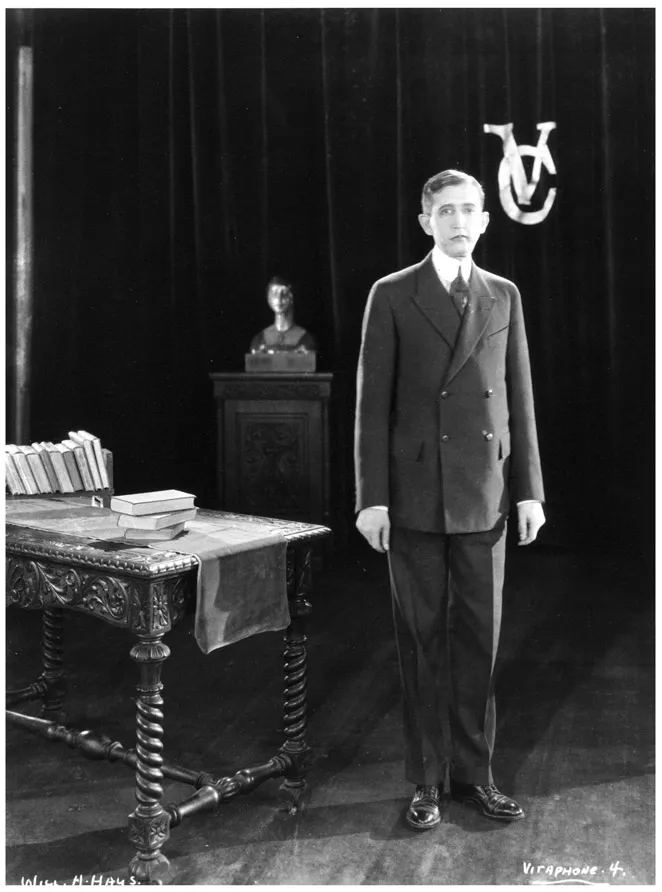

This entertainment business consolidated its power through horizontal integration. In 1922, U.S. companies got together to establish the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), a powerful umbrella organization of Hollywood studios.10 The head of this organization was Will H. Hays, former Postmaster General during the Harding administration. Intent on salvaging the industry’s public image from tabloid scandals and unflattering rumors, Hays, the “movie czar” from Indiana, launched an extensive public relations campaign.11 In 1934, the MPPDA established the Production Code Administration (PCA), a self-censorship apparatus that imposed strict rules regarding morally and politically questionable representations.12 Under the leadership of a confident spokesperson, Hollywood transformed into a “mature oligopoly” of the Big Five (Warner Bros., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount, Twentieth Century–Fox, RKO) and the Little Three (Columbia, Universal, United Artists) studios.13

Figure 1.1. Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Madison, Wisconsin.

The MPPDA’s activities were hardly confined to the domestic sphere. While taking pains to consolidate the industry’s standing at home, it pushed for an “open door” to gain access to markets abroad.14 In order to better engage with the international arena, Hays founded a Foreign Department within the MPPDA and appointed Frederick “Ted” Herron, a longtime acquaintance, to lead. During his decade-and-a-half of service, Herron tirelessly labored to represent the industry abroad while balancing the interests of member studios at home.15 The Hays Office also responded to foreign complaints about on-screen content. In order to finesse and diffuse international critics, the MPPDA regularly consulted with studio heads to forge “appropriate” on-screen content. Internal discussions were often geared toward the elimination of offensive caricatures of the on-screen Other.16

The Hays Office’s commitment to international trade also brought the industry closer to the U.S. government. Capitalizing on his connections with the Republican establishment, Hays in 1924 requested that the Department of State appoint an official to work specifically with the MPPDA.17 In response, the State Department agreed to assist Hollywood’s negotiations with foreign officials and captains of industry.18 The Department of Commerce became an ally as well. Acknowledging that Hollywood was of “great importance” to America’s world trade, the Motion Picture Division of the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce handled information on censorship regulations, tariffs and tax policies, copyright rules, and other issues that surfaced in foreign markets.19 Nathan D. Golden, assistant chief of the division, vowed to extend “every possible assistance in organizing, developing, and maintaining a profitable export business.”20 The Commerce Department enlisted a widely used slogan in support of Hollywood: “trade follows the motion pictures.”21

The efforts to globalize Hollywood came with high rewards. Studio executives and others commonly noted that 30 –40 percent of the industry’s earnings came from overseas during the interwar era.22 Although the demographics of “Hollywoodization” stretched across the world map, the primary focus of U.S. studios was Europe, which regularly generated as much as two-thirds of the industry’s foreign returns. Hollywood’s success across the Atlantic owed to the high market value of U.S. films and the direct-marketing campaigns of studios, as well as the MPPDA’s intervention.23 The performance o...