1

The City of Saint Teresa

The history of Saint Teresa’s city begins in the violent struggles of Spain’s medieval Reconquest from the Moors. The North African Muslims first invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 711 A.D.; three years later they conquered the previously Roman, then Visigothic, settlement known as Abula. For over three hundred years Christian and Muslim battled for possession of this region high on the central Castilian plateau, with its strategically located mountain passes between the Duero and Tagus valleys. Beyond the sierra lay the Visigothic capital of Toledo, the key to the domination of Castile. The area fell alternately into Moorish and Christian hands, and constant warfare reduced it to a barren no-man’s land.1

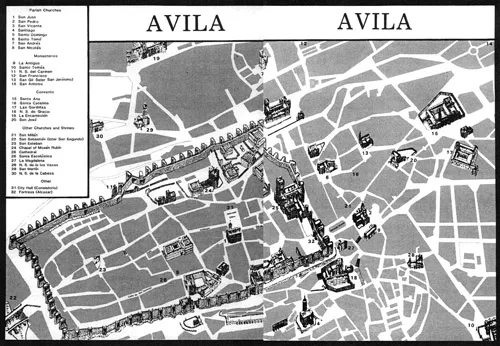

Finally, in 1083, Christian forces under King Alfonso VI of Castile gained definitive control; two years later they occupied Toledo. Alfonso charged his son-in-law, the French knight Raymond of Burgundy, with establishing a new city on the site of the old Abula. In what is referred to as Avila’s Repopulation, settlers arrived from northern Spain and France to found the frontier city.2 Many landmarks, such as the Cathedral of San Salvador, the beautiful basilica of San Vicente, several parish churches, and most important, the massive city walls, were constructed during the Repopulation of the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. Designed by foreign “masters of geometry” and built in part by Moorish prisoners of war, the formidable walls of Avila were meant to last centuries, for enemies still threatened the city on all sides.3

In this “society organized for war,” military strength and prowess were highly valued.4 Ennobled warriors quickly came to dominate a city of residents dependent upon them for protection. The legacy of military activity and noble hegemony would continue to influence Avila throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period. The city came to be called Avila de los Caballeros, Avila of the Knights.

Occasionally women penetrated this man’s world of warfare. A popular legend of medieval Avila celebrates a certain Jimena Blázquez. According to the story, once, in the early days of the Reconquest when all the men were away at battle, the Moors surrounded the city, confident of its easy capture. But Jimena Blázquez, the valiant wife of the royal governor, organized all of Avila’s women and inspired them with courage. Dressed in their husband’s hats and armor, the women climbed the battlements and furiously clattered their pots and pans. Hearing the dreadful clamor, the Moors feared that there were twice as many warriors as usual and fled without a fight. In some accounts, the grateful city offered Jimena Blázquez and her sisters full status as citizens (vecinos) and the right to vote in the concejo, or city council, but they refused this privilege.5

Whether or not Jimena Blázquez actually existed, her legend illustrates certain values. In this male-centered society, women who demonstrated toughness, initiative, and independence were thought so unusual that they were labeled (by male writers) varonil, manlike. Jimena Blázquez, noisy, brave, and arrayed in armor, in some sense became male and, by becoming male, achieved honor and greatness.6 Her refusal to accept political power is consistent with ideas regarding female abnegation and humility, however. One wonders if this part of the legend was formulated at a later date to justify the complete exclusion of women from the political scene. We shall see that, although internalized and spiritualized, the ideal of la mujer fuerte, “the strong woman,” persisted in Avila well into the seventeenth century.

By the late Middle Ages, the city had acquired another name, Avila del Rey, Avila of the King, which was also the device borne on its coat of arms. Avila established close ties with the Castilian monarchy, sheltering the boy-king Alfonso XI during his minority in the early fourteenth century and receiving many royal privileges in return. The city attained the right to send its representatives to the cortes, a parliamentary assembly. In the troubled mid-fifteenth century, influential citizens of Avila, perhaps precisely because of their strong conception of kingship, opposed the vacillating and reputedly impotent king Henry IV in favor of his half-sister, the princess Isabella.7 Moreover, Isabella was an abulense, a native of the province of Avila, born in Madrigal de las Altas Torres in the extreme north and raised in the convent of Santa Ana in the capital. Avila’s gamble paid off as Isabella won her bid for power. Thus, by the end of the fifteenth century tight bonds between city and monarchy had once again been forged.

Avila at the Birth of Saint Teresa

When Teresa de Ahumada y Cepeda was born in 1515, Avila could claim between four thousand and six thousand inhabitants. Like other European cities at the time, Teresa’s birthplace was just beginning a period of sustained demographic and economic growth. Because this period essentially coincided with Teresa’s lifetime, the saint grew up in an atmosphere of dynamic, but sometimes disturbing, urban change.8

Sixteenth-century Avila was an amalgam of diverse social groups. Even in the city’s earliest frontier days, residents organized themselves in barrios or neighborhoods according to occupation, rank, and ethnic diversity. These criteria formed the basis of the city’s social geography.9

In 1515 most abulenses worked as artisans, especially in the manufacture of woolen cloth. Simply put, wool production was the backbone of Avila’s, and of Castile’s, economy. At the end of the fifteenth century, the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, had taken measures to encourage sheepraising in Castile, giving nearly free rein to the mesta, the powerful herders’ guild. Most of the highly prized Spanish merino wool was exported to foreign manufacturing centers, particularly those in Flanders. Some, however, was kept within Castile, providing the raw material for a native cloth industry.10

Avila’s location virtually ensured its participation in this vital and lucrative wool trade. One of the three major royally protected systems of sheepwalks, the Segovian, passed through the province. This route of transhumance originated in the northeast corner of Castile, in La Rioja, and linked the cities of Burgos and Segovia, the financial and industrial centers of the wool trade. The massive herds of sheep were pastured in the mountains in the summer, and in winter they migrated west and south through the province of Avila, entering the warm plains of Extremadura through passes in the Val de Corneja. For this reason, many placenames in Avila contain the word Cañada (sheepwalk).11

Much of the wool raised in the province, especially that used for making high-quality cloth, went to the nearby city of Segovia. Dozens of men and women in Avila, however, found employment in the production of the cheap, coarse woolens made mainly for local consumption. About 20 percent of Avila’s active population was involved in the production of textiles in the early part of the sixteenth century. By the 1560s and 1570s this figure rose to over 30 percent.12

Avila’s numerous wool workers—weavers, dyers, carders, combers, spinners, fullers—as well as artisans involved in leathermaking, metalworking, construction, and other trades, clustered in certain neighborhoods. One of these was las Vacas, located outside the city walls. Enrique Ballesteros, a local historian of the nineteenth century, commented in describing this section of Avila that it had always been inhabited by “people of the most humble condition.”13 When the holy woman Mari Díaz moved to the city in the 1530s, she settled among the artisans and laborers of las Vacas. Her neighbor, the father of the future priest Julián de Avila, worked, according to the cleric’s biographer, as a weaver.14

The barrio of San Esteban, sloping west of the city’s center, lying roughly between the small church of San Esteban and the ancient bridge on the Adaja River, was Avila’s “industrial end” par excellence. In his 1609 history, Luis Ariz recounted its settlement by “men who performed the mechanical arts, dyers, tanners, millers, fullers and halberd-makers.”15 In the seventeenth century, Gil González Dávila attested to the operation of seventeen grist mills on the banks of the Adaja, as well as several fulling mills and washing troughs for the production of various grades of woolen cloth.16 San Esteban also gained a reputation as a bad neighborhood, at least in the eyes of the political and ecclesiastical elites whose opinions have come down to us. Behind the church of San Esteban, for example, stood one of Avila’s casas de la mancebía (houses of ill repute).17

Most of the evidence for the unsavoriness of this area is derived from the debate over the proper location for the relics of Avila’s first bishop, San Segundo, discovered in 1519 in the chapel of San Sebastián on the Adaja, across from a large grist mill. González Dávila, some forty years after the relics had been transferred to the cathedral, cited among the reasons for the move that the place was inconvenient, that “the maintenance of the physical plant was very poor,” and that “the faithful attended very infrequently because of the great distance of the chapel.” Attendance at the shrine was, in fact, enough, but not by the class of people who would have to travel through the “bad part of town” to get there.18 The ecclesiastical notary Antonio de Cianca, a major proponent of the move, pointed to the proximity of the chapel to foul-smelling tanneries, the animals that wandered unchecked into the shrine, and the thieves and “low-life men and women who [went] there to chat and have lascivious relations.” And although the patrons of the neighborhood-based confraternity protested that the chapel was in a “comfortable and cheerful location, well above the river, mills and tanneries,” in 1594 Avila’s bishop and cathredral canons decided that the sacred relics, for security reasons must be placed “in the middle of the city” (that is, where the upper class lived) and out of this “bad neighborhood of tanneries and mills and other inconveniences caused by the animals.”19

Perhaps we should not be surprised that city elites eventually succeeded in having the body moved. More remarkable is that the brothers of the San Segundo confraternity managed to keep the saint’s relics for some seventy years in a peripheral neighborhood where thieves and prostitutes mingled with artisans and visiting peasants, the incessant sounds of mills grinding grain and fulling cloth filled the air, and the unpleasant smells of tanned leather, dyestuffs, and manure filled the nostrils.

More centrally located were Avila’s two marketplaces, the Mercados Grande and Chico. Here commerce and trade flourished in the early sixteenth century as the city played an important role as a regional distribution center. Numerous fairs and markets attracted farmers from the surrounding countryside and brought business to shopkeepers and dealers in agricultural products as well as revenue to the city government. Municipal ordinances promulgated in 1485 mention the market held every Friday in the Mercado Chico, a tradition that continues to this day.20 Avila’s commercial district also provided a place for gossi...