1

E PLURIBUS UNUM

“The community of central bankers transcends every political form of government.”

—Senior vice president, Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2001)

The Hungarian central banker leaned in. He had something important to tell me. In mixed groups, he said, you can always spot the central bankers. “How? By their club ties and secret handshakes?” I asked jokingly. He laughed and replied that central bankers “use the same language, have the same culture. I mean, sometimes it’s strange how central bankers think.”1 In conversation after conversation, central bankers from postcommunist countries told me that their compatriots around the world shared a bond, a unique set of concerns and priorities, and a similar way of thinking and acting. As newcomers to this community, they were particularly attuned to its norms and practices. Established central bankers, though more sensitive to the distinctions among individual personalities and institutions, concurred that central bankers had much in common.

Indeed, by the late 1980s central bankers across the advanced industrial democracies had come to form a cohesive transnational community. Its core institutional members included national central banks such as the Bank of England, the Deutsche Bundesbank, and the US Federal Reserve, as well as the Basel-based Bank for International Settlements and key departments within the International Monetary Fund. The subsequent establishment of the European Monetary Institute and its successor the European Central Bank, created through the joint efforts of West European central bankers, further consolidated this community. While central bankers had worked together on many occasions in decades past, they achieved a qualitatively new level of collaboration in the 1990s. Convergences in economic theory and practice, technological advances easing international communications and travel, central bankers’ increasing autonomy from their national governments, and the challenges of financial globalization all conspired to bring central bankers together intellectually and professionally as never before.

This community shared two key operational principles. Most fundamentally, central bankers came to agree that a central bank’s primary task should be to maintain a low and stable inflation rate, which they referred to as price stability. Moreover, because policies aimed at achieving price stability could be politically contentious, central bankers further agreed that they needed significant independence from their governments in order to do their jobs properly. The community regularly celebrated and promoted these principles in multiple forums around the world. As a high-level IMF and former US Federal Reserve official told post-Soviet central bankers in 1994:

Since the 1980s, there has been a convergence in thinking with respect to two ideas about central banking: first, that a central bank’s main mission should be to pursue and maintain price stability as the best strategy for sustainable economic growth; and second, that to achieve its main objective, a central bank should be independent from political influences.2

Central bankers generally agreed that if independent central banks successfully pursued price stability, growth and employment would follow. Economic results seemed to prove the worth of the two principles, as the progressively wider adoption of laws guaranteeing central bank independence and central bank policies focused on price stability in the late 1980s and 1990s coincided with an era of low, stable inflation and steady output growth in the advanced industrial democracies. Even the US Federal Reserve, which had an unusual and politically sacrosanct dual legal mandate to pursue both price stability and maximum employment, in practice privileged its price stability objective during this period.3 Central bankers called the halcyon years before the 2007–8 global financial crisis the Great Moderation, in capital letters. The Great Moderation raised central bankers’ self-confidence and governments’ confidence in their central banks. This general agreement on basic principles provided a powerful intellectual platform from which central bankers could work together and advance their shared interests.

At that same historical juncture, the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union imploded—and a moment of consensus met a window of opportunity. Central banking as it had evolved in the Soviet bloc was unsuitable for managing market economies and would need to adapt to the changing circumstances. The members of the transnational central banking community thus set out collectively and individually to help the postcommunist countries create central banks molded in their own image: independent, technocratic, respected anti-inflation warriors.

The Transnational Central Banking Community

Who were these “established central bankers”? The transnational central banking community comprised far more than a handful of celebrity governors, although one might not know it through reading popular accounts of central banking. Although leadership and personalities are incontrovertibly important, like any bureaucracy central banks have large professional staffs whose collective efforts and expertise matter in policy formulation and implementation. Central bank governors set the tone and general directions for their banks, but it is the staff who develop the models, organize the data, crunch the numbers, arrange the meetings, analyze the possibilities, and write the reports on which day-to-day decisions and operations rest. Most important for our purposes, the expert staff design and implement central bank training and technical assistance programs. Governors may give grand speeches about central banks sharing knowledge and practices with each other, but they would be the first to admit that dedicated staff members did the real hands-on work. Therefore, understanding the community’s character requires acknowledging the norms, practices, and hierarchies that extended within and across central banks and their close institutional allies, from the governors on down.

In doing so I focus on the four interlocking characteristics that made the central banking community unusually cohesive at this historical juncture: its widely shared principles and practices, its unique professional culture, its transnational infrastructure, and its relative insulation from outsiders. These characteristics yielded a particular kind of transnational community, one that interacted, learned, and disseminated knowledge through what I call a worm-hole network.

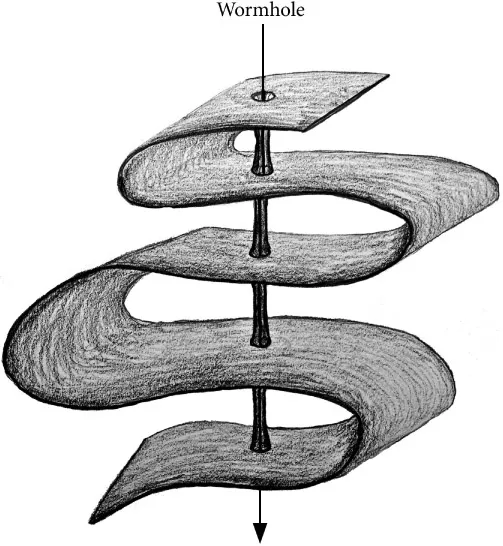

FIGURE 1.1 Artist’s rendition of a wormhole. J. E. Theibert 2014.

In physics, a wormhole (or more formally, an Einstein-Rosen bridge) is a shortcut between two distant points in space-time, making otherwise faraway places immediately accessible to one another. Imagine drawing dots on either end of a piece of paper; normal travel between the two would require traversing the distance across the paper, but by folding the paper in half the dots meet instantly on top of one another. In essence, a wormhole is a bend forming a tunnel in space-time. I use the metaphorical phrase wormhole network to refer to interconnected “tunnels” of intense transnational interaction and cooperation among similar institutions and actors physically located in multiple countries— in this case, central banks and bankers.4 Figure 1.1 illustrates a wormhole cutting through folds in space-time from what would otherwise be distant points to form such a tunnel.

Wormhole networks became possible in the digital age with the rise of sophisticated electronic communications technology and routinized international travel. A wormhole network entails constant transnational interaction, socialization, and ideological reinforcement within the network, but is thickly bounded to restrict access by outsiders. It is composed of individuals with similar professional training, worldviews, and work practices who interact regularly and cooperatively in formal and informal ways, maintain and create institutions to facilitate and reinforce this interaction, and share a distinct community identity that transcends state boundaries and is reflected in a shared mission, specialized discourse, and self-referential interaction pattern. The wormhole must be opened, purposefully maintained, and naturalized through extensive and focused community effort.

Figure 1.1 helps to visualize the simultaneously close yet internally hierarchical nature of the network. The most powerful and prestigious community members are metaphorically located at the entrance to the wormhole, while as one progresses further through it one finds the newer, follower, slightly more heterodox, and otherwise less core members. In that sense, there is a certain distance and differentiation within the community. Yet those distances pale beside the greater distance between the community members and outsiders. This has important governance ramifications. The socialization and communication across a wormhole network reinforces internal ties and encourages community members to feel closer to their transnational peers than to noncommunity actors within their own countries. That is, by enabling and privileging close transnational connections, a wormhole network simultaneously de-emphasizes or even degrades national ties. It is thus exceptionally well suited for facilitating community mobilization and for rapidly transmitting information and ideas within the network, but can make it more difficult for community members to interact effectively with nonmembers or to acknowledge and learn from conflicting views originating from outside the network. As a wormhole network, the transnational central banking community was both closely connected internally and relatively insulated externally. This represented a source of strength in its efforts to integrate postcommunist central bankers into the network, but a potential liability when the global financial crisis later challenged the community’s fundamental principles and practices.

Principles and Practices

The community shared the interdependent principles of price stability and central bank independence, which in turn generated a range of corollary beliefs and practices.5 Price stability meant maintaining a stable and low rate of inflation, typically as measured by the consumer price index. As the BIS’s Claudio Borio put it in a retrospective on the Great Moderation era, “the prevailing pre-crisis consensus had gravitated towards a ‘narrow’ view of central banking, heavily focused on price stability and supported by a belief in the self-equilibrating properties of the economy.”6 Independence, in turn, allowed central bankers to credibly commit to pursuing price stability because it would prevent politicians from manipulating the money supply to boost their political fortunes.7 Delegating authority over monetary policy to technocrats allowed a government to tie its own hands for the greater economic good. In practice, granting independence to a central bank meant passing legislation to shield its officials, budgets, and decision-making processes from overt political interference. This legal independence was intended to give central bankers the freedom to make potentially painful policy decisions without fear of immediate retribution.

Three corollaries evolved from these core principles. First, public expectations mattered. In order for a central bank to achieve price stability, the public had to believe that the central bank possessed the tools and the freedom to restrain inflation. In other words, central bank actions had to be credible in order to be effective. Alan Blinder, former vice chairman of the US Federal Reserve Board of Governors, found in his 1999 survey of eighty-four central bank governors that they deemed “credibility” to be “of the utmost importance” for a central bank.8 Credibility ideally required effective communication, a simple and clear price stability mandate, an independent central bank, and well-calibrated monetary policy instruments. Second, central bankers saw no long-run tradeoff between inflation and either unemployment or output. This consensus emerged from academic research in macroeconomics and underpinned central bankers’ justification for their narrow focus on price stability. Finally, central bankers came to believe that they should not use monetary policy to preemptively address asset price bubbles. The value of assets such as housing, equities, and gold not only rose and fell in a natural cycle, they argued, but monetary policy represented a poor tool with which to moderate that cycle. Attempting to “lean” on such bubbles would only detract from a central bank’s ability to pursue its core mandate, stabilizing consumer prices. This view was at the heart of the so-called Jackson Hole consensus, named after the legendary annual conference hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.9

Several “best practices” emerged from these principles and corollaries. Most notable was the rise of inflation targeting as a method of credibly committing to price stability.10 An inflation-targeting central bank publicly states that it aims to use monetary policy to achieve and maintain a predetermined inflation rate over a set term. Inflation targets became popular because they were easy to explain and represented a concrete commitment to pursue a specific definition of price stability. The European Central Bank’s informal inflation target of “below, but close to, two percent” reflected a community norm. After New Zealand adopted the first formal inflation targeting policy in 1989, many other central banks followed its lead, including the central banks of Australia, Canada, Israel, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. All had inflation targets set at 3 percent per year or less.11 The US Federal Reserve later found itself under a two-term governor, Ben Bernanke, whose academic research had str...