II

ARRIVALS

The stream of Tongan emigrants began in the 1950s as a trickle. They were temporary migrants, sent by the church or family for education overseas.1 They were single men looking for the high wages of unskilled overseas work. Their primary destination was New Zealand, the closest industrial nation at 1,300 miles away.

Leaving Tonga was the culmination of many forces both inside and outside Tonga, as you saw in the last chapter. Conditions throughout the twentieth century had produced rising commoner expectations for mobility. By the 1950s, the first generation of educated commoners had begun to take their place in government, and many farming households were producing copra or crops for sale overseas. Over the next twenty years, however, a dwindling land base and limited jobs would prevent many commoners from realizing their climbing aspirations.

By the 1960s, the stage was set for migration. Overseas wages could provide a bridge between commoner aspirations and opportunity, and it was under these conditions that labor needs in industrial countries easily triggered movement out of Tonga.

The Mormon Church in Tonga was instrumental in the early migration of Tongans to the United States. The church funded the migration of hundreds of Tongans to Mormon centers in Hawai‘i and Salt Lake City. Without a village context for viewing migration, one might interpret Tongan migration to the United States as a religious phenomenon, motivated by a commitment to the American-based Morman Church. It is more accurate to say that the Tongan commitment to the church was motivated by the opportunity it provided for overseas migration. The fact that the Mormon Church facilitated the migration of Tongans to the United States was one of the major reasons why Mormonism was the fastest growing religion in Tonga during the 1960s.2

By the 1970s, the Tongan government had become actively involved in enabling Tongans to work temporarily overseas. Migration solved a growing problem of land, jobs, and population for the Tongan government. The population of Tonga had continued to climb throughout the 1960s against a backdrop of land scarcity. Despite government efforts at increasing employment in the public sector, and various schemes to develop local industry, there were not nearly enough jobs to absorb those who sought work. A 1972 government report determined that only 5 percent of school leavers (Tonga’s high school graduates) would find paid employment.3 With government encouragement and the demonstrated promise of remittances, migration out of Tonga during the 1970s (primarily to New Zealand and Australia) became substantial, and significant at the national level.

It was during this time that United States immigration laws changed dramatically. Before 1965, immigration law was based on country quotas that heavily favored European nations and discriminated against the Asia-Pacific triangle. Two changes were initiated, beginning with the Immigration Act of 1965, that repositioned the United States as a destination for Tongan migrants. First, the national origins quota system limiting the number of visas granted to each country was abolished.4 Visas would be granted on a first come, first served basis within a preference system that encouraged the uniting of families. Second, included in the new laws was a visa preference category (called the Fifth Preference) for the uniting of siblings. This came to be the most frequently used category of immigration applications, and it allowed early Tongan migrants to bring over their sizable sibling networks. Asian and Pacific Islander immigration increased sixfold by the late 1970s.5

By 1980, more than 5,000 Tongans had made their way to the United States, and the next decade was to see these numbers swell as each stream of migrants brought over the next. By 1990, the United States had become the preferred destination of Tongan emigrants. An estimated 25,000 Tongans (both Tongan-born and American-born) were living in the United States in 1995, equal to more than one-quarter of the entire population of Tonga.6

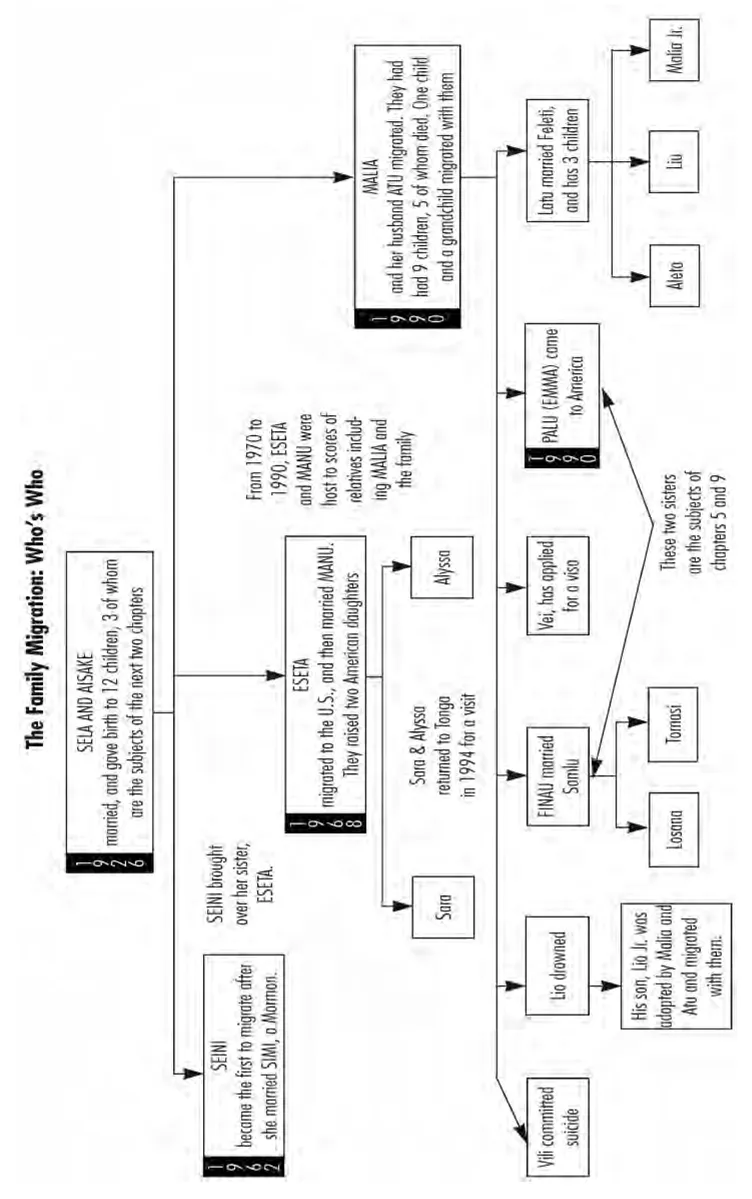

The next three chapters describe the histories, thoughts, experiences and words of Tongan migrants to the United States. The people you will meet are all part of one extended family whose home was originally in ‘Olunga. They migrated from Tonga to the United States at different times, from 1963 to 1990. You will encounter these migrants, and their relatives who did not migrate, throughout the book. The reference chart of names and relationships on page 55 is a convenient guide for remembering who is who.

Chapter 3 begins in 1963 with Seini, the third-born child of a family of twelve, who was the first of her siblings, and among the first few hundred Tongans, to come to America.7 From 1965 on, she and her Mormon husband began bringing over their extended families. Chapter 3 focuses on the first sister she brought over, Eseta, and her husband-to-be, Manu, who settled together in northern California and brought up two American children. It is through Eseta and Manu’s family that you will see Tongan life in America.

In the years after Eseta and Manu migrated, emigration from Tonga to the United States burgeoned. More than 17,000 Tongans were legally in the United States by 1990, and California had become home to almost half of them.8 San Mateo County, Eseta and Manu’s place of residence, had become a small center of Tongan community in the United States, home to 2,600 Tongans by the early 1990s.9

Chapter 4 follows one family of these new migrants, Eseta’s sister Malia and her family, as they moved from ‘Olunga in 1990 to San Mateo, to live for their first year with Eseta. Chapter 5 describes the life memories of a young woman in this Tongan family, the only one of four sisters who decided to migrate. She talks about her childhood and her decision to leave. You will see her life five years after her migration as she has “Americanized” and plans on staying permanently in the United States. (The story of her older sister, who came on a visit but decided to stay in Tonga, is the focus of chapter 9.)

The final chapter in Part II describes an arrival in a different direction: the anthropologist’s arrival in Tonga. Chapter 6 recounts significant incidents that occurred over a fifteen-year period, beginning with the author’s formal fieldwork and extending to the new dimensions of experience that unfolded as Tongans continued to migrate to the United States.

More than most other chapters in the book, the chapters in this section (and chapter 9 as well) rely heavily on the words and remembered histories of family members. Stories that were told in English are reproduced nearly verbatim, with a minimum of editing of content or grammar. The interviews conducted in Tongan, or those recorded with notes and without a tape recorder, are my translations. I have tried to remain faithful to the tone and text of what was said. Where you hear people recounting their own life stories, I include my own questions so the reader will understand better the context in which the story was told.

Other chapters in this book are written to make particular points and to defend particular arguments. These chapters, which draw on people’s narratives of their lives, are written differently because there is always more to people’s lives than the points I might wish to make with their stories. There is certainly much to learn in these chapters, from the diverse reasons why people came to this country to the striking social distance between Tongan migrants and the dominant society to the generational gap between migrants and their children. However, the life histories in these chapters, while focused by questions and edited somewhat, take their own dips and turns. I offer them to you as material worth reading in its own right.

3

Coming to America

Eseta wanted to go to America because of her sister Seini.1 Seini was the first in the family to leave for overseas. A nurse in Tonga, she worked at the island’s only hospital. One year Seini tended to an older patient whose son came to visit his father regularly. That is how she happened to meet her husband, Simi, a teacher and a Morman from a different village. When they married in 1958, Seini converted to Mormonism. The Mormon Church was already funding Tongan congregants to come to the United States, and in 1963, when the church offered Seini and Simi the opportunity to go to Hawai‘i, they took it.

They arrived in Oahu. Simi, the teacher, worked in a warehouse. Seini, the nurse, worked as a nurse’s aide in a convalescent home. They soon moved to California, and Seini and Simi began bringing over family. First, they arranged the trips of Simi’s father and brothers and their children. Next, Seini wrote to her sister Eseta to come. Eseta recalled:

I stayed home—I was the only unmarried one—and I took care of my parents. My sister Seini would send us money to help, when my father was still alive. She wrote me to come there. She told me, “Oh, you have to come here and work to have your family. It’s better here.” So I decided I must go. So I forget everything else: friends, making tapa cloth. I decided I would go to America.

I did have a “best friend” [boyfriend] though. He left first and went to Samoa and waited there for me. We were supposed to get married in Samoa, and then come over to the U.S. And when I went to Samoa to meet him, right on the plane, I changed my mind.

Eseta knew that if she married her fiancé, they would stay in American Samoa. Getting to the United States would still be far off. She recalls thinking on the plane trip from Tonga, “Please don’t let me stay in Samoa.” The groom, his father, and his family were waiting in Samoa for her to arrive, but her own family, knowing her feelings, telephoned her relatives in Samoa. By the time she got there, her relatives had already talked to the boy’s family and had arranged for Eseta’s plane ticket to the United States. The family’s reasons for interfering with the marriage were different from Eseta’s; the boy was not from the same church as Eseta and they disapproved. The family, of course, did not say so directly. They talked about the need to wait awhile before getting married, about how Eseta should take a trip to the United States and then come back.

So when Eseta landed in Samoa, a relative met her at the airport. The marriage was off, and she was scheduled on a departing flight to the United States.

Were you happy with that?

Oh, yes. I went to see my boyfriend and I told him, “You stay here. I’ll be back. In five years.”

Did you ever want to just go back to Tonga?

No. Except the first week I came—staying with my sister. I didn’t work yet. Then I felt homesick. I said I wanted to go back. And then the very first time I worked—it was too early for me to wake up. “It’s still night!” I said to myself. My first job I had to be at work at 7 A.M. So I had to get up at 5:30 A.M. It was dark. But after this, I was never homesick.

When I first came, I sewed for money. Then I got work in a hotel. I sewed eight hours a day, and then weekends I was a maid. When I got my first paycheck, I gave some to my sister, and every week I do the shopping for the whole family. So I bought food. And I worked for my green card.

I never spent much, though. Food was cheap. A whole bag of potatoes was twenty-nine cents. A whole chicken was twenty-nine cents. Eggs were nineteen cents for a package. After a few years, everything jumped up. Those were hard times, though. I didn’t have a car. I walked everywhere. My brother-in-law sometimes dropped me at work in the morning, and then he’d go to work and I walked home. It was two miles.

In those days, I spent nothing. I spent only a little on food, and saved every dollar to buy a used car for myself. In a few months I had a car already. I asked a friend to teach me to drive, a Tongan girlfriend. We went to open parking lots, and she taught me. She showed me everything. Then I moved to a place of my own.

Eseta and Manu

Growing up, Eseta and Manu had seen a lot of each other at Viliami’s store and roller rink in the village of ‘Olunga. Manu had worked there for seven years before going to New Zealand. A roller skating rink was an unusual thing to have in a Tongan village. Built by Viliami, a Swiss national who settled in the village after World War I, it became a centerpiece of village life which villagers today remember fondly as part of their growing up.

Eseta loved to skate. For Eseta, who was shy and did not socialize easily, going to the skating rink was a passion she pursued with enthusiasm. Eseta’s mother remembered that she would steal away to the rink every moment that she could. It was here that Eseta met Manu, but, as she says, “We were just friends. Not one who I thought of to marry.”

Manu had not intended to marry Eseta, either. After many years of thinking about going overseas, Manu finally went to New Zealand in 1966 to work, when he was already thirty-nine years old. Manu had been interested in New Zealand ever since he was fifteen, when he befriended a New Zealand soldier who was part of the island’s occupying force during World War II. New Zealand suited Manu, as he told the story at age sixty-five:

I loved New Zealand. Up until today, I like New Zealand better than the United States. Because I like New Zealand air. Some people they say it’s too cold, but it wasn’t cold to me. Only on the mountain do you see white—but in the town, no frost, no snow. I loved New Zealand. But I hear now it’s the same everywhere. It changed from before.

After fifteen months working in New Zealand, Manu returned to Tonga in 1967 with the intention of marrying a girl from the village and returning with his new wife to New Zealand and settling there. But then his plans changed suddenly.

I was supposed to go and marry this girl on Wednesday. But on Monday I told her, “Don’t let your family know. If they know, they’ll object.” On Monday, she decides to talk to her family. The family says no!

So after that, I was really mad—so I wrote a letter to Eseta. And I told her I wanted to marry her. I had been at the kava circles where Eseta made kava many times. I know her and she know me. I told the guy who wanted to marry her, “In my mind, you can’t find anybody like Eseta. That’s why I think you should go marry her.” And he left to marry her. But when I got to Samoa, I saw that he had married with someone else—someone in my family, not her.

So then I thought I want her for my wife. I write this to her (not her father). I want her to come back and go to New Zealand because...