1

OUTSOURCING HORROR

Why Apparel Workers Are Still Dying, One Hundred Years after Triangle Shirtwaist

Scott Nova and Chris Wegemer

The fire broke out at 5:30 p.m., right after the bell sounded the end of the workday. The building is 10 stories high. The Triangle Waist Company occupied the top three floors, and that is where the fire started … The flames spread very quickly. A stream of fire rose up through the elevators to the uppermost floors. In the blink of an eye, fire appeared in all the windows and tongues of flame climbed higher and higher up the walls, as bunches of terrified working girls stood in astonishment. The fire grew stronger, larger and more horrifying. The workers on the upper floors were already not able to bear the heat and, one after another, began jumping from the eighth, ninth and 10th floors down to the sidewalk where they died.

—The Forverts, March 26, 1911

Survivors have described how a fire tore through a multi-story garment factory just outside Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, killing more than 100 of their colleagues … Muhammad Shahbul Alam, 26, described flames filling two of the three stairwells of the nine-floor building—where clothes for international brands … appear to have been made … Rooms full of female workers were cut off as piles of yarn and fabric filling corridors ignited. Reports also suggested fire exits at the site had locks on, which had to be broken in order for staff to escape … Witnesses said many workers leapt from upper stories in a bid to escape the flames.

—The Guardian (Burke and Hammadi), November 25, 2012

Time and again when workers speak up with concern about safety risks, they aren’t listened to. And in the moment of crisis, when the fire alarm goes off or a building starts to crack, workers’ voices not only fall on deaf ears, but they are actively disregarded … Change can happen. It is happening. But there’s still a long way to go.

—Kalpona Akter, Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, January 23, 2014

On March 25, 1911, on the top floors of a ten-story building on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place in lower Manhattan, a fire broke out in a factory operated by the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. As smoke and flames rapidly spread, a lack of fire exits made escape impossible; workers desperately scrambling for egress found only locked doors. Many chose to leap to their deaths rather than succumb to the flames. One hundred and forty-six people, mostly young women in their late teens and early twenties, died in a tragedy that helped catalyze a national movement for workplace reform.

Unfortunately, we don’t need a history lesson to contemplate the horror of garment workers falling to their deaths from the high floors of a burning factory. The abusive conditions, poverty wages, and shoddy garment industry safety practices that unions and social reformers decried in 1911 have not disappeared. They have been relocated. Today, leading apparel brands and retailers produce their goods in countries like Bangladesh, now the world’s second-largest garment exporter, where from 2005 to 2013 nearly two thousand workers were killed in more than a dozen fires and building collapses. Each of these disasters arose from the same kind of reckless disregard for worker safety that produced the tragedy at Triangle Shirtwaist.

Thanks to decades of legislative reform and union activism, by the 1950s apparel production in the United States came to be defined by decent wages, strong unions, and enforceable safety regulations. However, as communications and transportation technology made overseas production increasing feasible, clothing brands and retailers eventually relocated the manufacturing of garments to countries that offered what the United States no longer did: workers willing to toil for poverty wages and governments willing to turn the other way while factory managers cut costs by ignoring labor standards. It is important to bear in mind that low wages, though important, were never the sole attraction; the savings that can be derived in an environment of lax-to-nonexistent regulation are also substantial.

Unconstrained by regulation, apparel producers in 1911 Manhattan did not waste money on niceties like workplace safety. Neither do their counterparts today in Bangladesh and many other garment-producing countries. Leading Western apparel brands and retailers have thus accomplished a perverse form of time travel: they have re-created 1911 working conditions for millions of twenty-first-century garment workers.

On no issue has the cost to workers been more obvious, or more tragic, than workplace safety. The garment industry has known for a century how to operate an apparel factory safely, a lesson learned in the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. Moreover, virtually every exporting country, including Bangladesh, has laws on the books that require proper building design and operation. Yet in Bangladesh, prior to recent reform efforts spurred by the Tazreen Fashions fire (November 2012) and the Rana Plaza building collapse (April 2013), it is highly likely that none of the country’s 3,500 garment factories had fire exits or sprinkler systems. Hundreds were structurally unsound. No factories were found to be even close to meeting safety standards (Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh 2014). As a result, millions of garment workers risked their lives every day merely by going to work.

This recklessness explains why, despite all of the last century’s advances both in the technical understanding of building safety and in the official recognition by governments and corporations of the rights of workers, three of the four worst disasters in the centuries-long history of mechanized garment production have occurred in the three years before 2015.

Only in the wake of the worst of these, the Rana Plaza collapse, which generated weeks of worldwide media coverage highly embarrassing to leading brands and retailers, was it finally possible to persuade some of these corporations to commit to take the action necessary to make garment factories in Bangladesh safe.

In the following, we discuss why preventable mass fatality disasters continue to occur in factories producing the clothing of major Western brands and retailers more than one hundred years after the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, the actions necessary to bring an end to this long season of horror, and the initial steps taken in this direction since the Rana Plaza collapse.

How We Got Here

Although apparel brands and retailers pay ample lip service to worker rights and worker safety, dangerous and degrading working conditions are a product of their own manufacturing strategies. Today’s global apparel supply chains have the following salient features: (1) brands and retailers generally eschew ownership of manufacturing capacity and instead assign their production to contract factories; (2) relations with these producers are defined by short-term contracts for specific orders of apparel with no guarantee of continued business; (3) brands and retailers usually limit their production in a given factory to a modest portion of the factory’s overall output, so factory owners must piece together numerous short-term orders from a long list of current and prospective customers in order to survive; and (4) with barriers to entry into garment production low, and with large numbers of workers desperate for some form of employment, there is excess capacity on the production side, allowing brands and retailers to bargain prices, and order deadlines, downward by exploiting competition between suppliers.

These factors combine to generate intense and consistent pressure on producers to cut costs, and therefore prices, by any means available; they understand that if they cannot meet a given customer’s price demands, there is another factory, across the street or across the world, that will. The options for reducing production costs are limited; factory owners have virtually no ability to reduce the cost of cloth, or of power, or of sewing machines. The one cost over which they can exert substantial control is labor.

The barrier to achieving large savings by squeezing labor—underpaying relative to the minimum wage, forcing workers to endure long hours of overtime, cutting corners on workplace safety, firing workers who try to unionize—is that apparel exporting countries generally have strong labor laws. In many cases, laws concerning such issues as mandatory benefits, limits on overtime, protection for women workers, and occupational health and safety are as strong as, or stronger than, those in the United States. If factory owners had to follow these laws, they would have about as much control over the cost of labor as they do over the cost of cotton. Fortunately for them, and unfortunately for those who sew garments for a living, governments are every bit as attuned to the priorities of foreign buyers and investors as local factory owners are. Believing, with strong historical basis, that brands and retailers will reward those countries that keep labor costs to a minimum and punish those that fail to do so, governments in apparel exporting countries are notoriously willing to abdicate regulatory responsibility.

Garment factory operators therefore have both powerful incentive (relentless pressure on price and delivery speed) and ready means (lax regulation) to reduce production costs by running roughshod over the rights of workers. This is the dynamic that explains the contemporary sweatshop and is at the root of every major category of labor rights abuse in the garment sector, including the heedless safety practices that have advanced the macabre parade of fires and building collapses in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

The astounding growth of garment production in Bangladesh is a testament to the overriding importance of cost reduction to brands and retailers and their willingness to tolerate abusive and dangerous working conditions as a means to that end, despite their public insistence that worker rights rank high as a corporate priority. Bangladesh offers very few advantages to brands and retailers: productivity levels have never been high, transportation infrastructure is shambolic and has been slow to improve, political instability is a constant threat (Berg et al. 2011). Meanwhile, the country’s record on labor rights is among the worst in the industry (Wood 2010; International Trade Union Confederation 2014; Human Rights Watch 2015a). Until the government came under significant pressure in 2013, there were no unions in Bangladesh, and in the face of continued resistance from factory management, less than 5 percent of workers are currently organized (Westervelt 2015). The “troublemakers” are fired, often threatened with police repression, and, increasingly, face violent retaliation (Ali Manik and Bajaj 2012).

How does a highly inefficient producer with a terrible human rights reputation become the second-largest garment exporter on the globe? It does so by offering labor costs lower, by a sizable margin, than any of its competitors—low enough to more than offset the inefficiency—and by betting that the unsavory means utilized to achieve those cost savings, and the ugly consequences for workers, will not deter brands and retailers from taking advantage.

The year before the Rana Plaza collapse, Bangladeshi garment factories exported garments worth more than $80 billion at retail, enough production to give two-dozen pieces of clothing to every person in the United States.1 The factories employ more than 3.5 million workers in the process, over a million more than were employed in the US garment industry during its mid-twentieth-century peak. Only China, the undisputed industrial behemoth of the early twenty-first century, has a larger garment sector than Bangladesh—and, with garment-worker wages in China now high by industry standards, at $1.25 an hour, Bangladesh and other super-low-cost producers are taking over a growing chunk of China’s business (BGMEA 2015).

Relentless Price Pressure

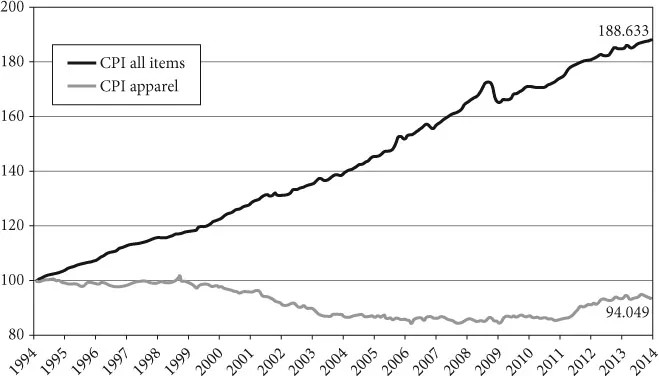

The relentless, and spectacularly successful, drive of apparel brands and retailers for lower production costs is reflected in the trend in the retail price of clothing. Between 1994 and 2014, the overall price of consumer goods in the United States increased by 87 percent; for apparel, prices declined by 6 percent (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015). This means that, after inflation, the price American consumers pay for clothing has dropped 50 percent over the last two decades.

Given the effect of low-cost imports on wages in the North, it is debatable whether saving a few hundred dollars a year in clothing costs represents a genuine benefit to Northern consumers; what is beyond dispute is that garment workers in the Global South pay for these savings in the form of depressed income and substandard conditions of work.

A recent study by the Center for American Progress and the Worker Rights Consortium found that the real wages of apparel workers in the large majority of top apparel-producing countries decreased substantially between 2001 and 2011; the study shows that the prevailing wage for garment workers in all of the countries was found to be a small fraction of a conservatively defined living wage (Center for American Progress et al. 2013). In Bangladesh, the minimum wage for garments workers is 32 cents an hour—after a 77 percent increase in 2013, implemented in the face of mass worker protests and growing international pressure on the Bangladesh government driven by revulsion over the Rana Plaza collapse. This 32 cents an hour is less than it costs a garment worker to shelter, clothe, and feed herself, much less her dependents.

FIGURE 1.1 The falling prices of apparel relative to all consumer goods

Failure of Corporate Self-Regulation

Low wages, abusive conditions, and disregard for workplace safety keep production costs low, but they also create risks for brands and retailers, as the Tazreen fire and the Rana collapse demonstrate. For apparel corporations, brand image and reputation are highly valued assets; devaluation of these assets, through association with sweatshop conditions, can yield lasting damage.

Faced with stinging criticism over conditions in their overseas factories, and forced to acknowledge that governments in the countries where they are producing do not regulate factories effectively, apparel corporations, beginning in the 1990s, publicly accepted responsibility for policing labor practices in their supply chains.2 Today, every major apparel brand and retailer has a labor rights “code of conduct” and a factory monitoring program, involving a pledge to regularly inspect their supplier factories using either in-house personnel or contract auditors, to press factories to correct any labor rights or safety violations identified, and to stop doing business with factories that refuse to comply.

This is not regulation, it is self-regulation. These are voluntary programs; brands and retailers promise to ensure respect for worker rights and worker safety in their supply chains, but they make no binding commitments to any third party. Whether apparel corporations follow through on their pledges is at their sole discretion. The monitoring process is controlled and run by the brands and retailers; the inspectors work for them. The brands and retailers tell the inspectors what to look for, exclude those issues they choose to exclude, and act—or don’t act—on the inspectors’ findings as they see fit. Public pressure to live up to their official labor rights promises can, in some circumstances, be brought to bear on brands and retailers, but the brands and retailers sharply limit transparency in order to minimize the ability of advocates to do so: inspection results are kept secret (from workers as well as from the public) and the only information that gets reported is what the brands and retailers choose to report (generally, glossy paeans to the great progress ostensibly being achieved, backed up by little to no hard information).

The official goal of these programs is in conflict with the brands’ and retailers’ short-term economic interests: it costs more to produce under good conditions than bad conditions. Factories that observe the minimum wage, pay required overtime premiums, refrain from forcing workers to stay overnight when orders are due, provide maternity leave where the law requires it, and invest in necessary safety equipment will have higher production costs than factories that ignore these requirements, and will therefore need higher prices. Thus if brands are successful in compelling their factories to come into compliance with the applicable local law and the brands’ own labor standards, the brands’ costs will increase and profits will be reduced accordingly. The cost impact of genuine compliance is modest, but significant, and cost sensitivity is deeply ingrained in the culture of the industry. Thus if brands and retailers faithfully carry out their labor rights pledges, they will produce a result that they otherwise strive relentlessly to avoid.

Given these realities, is not surprising that these programs have failed to achieve high levels of labor rights and worker safety compliance in global apparel supply chains. When the goal of achieving the lowest production costs comes into conflict with corporations’ labo...