Beethoven’s Weihekuss Revisited

The report of a Kiss from Beethoven after the concert cannot be true.

Walther Nohl

“But you received it.”

“Naturally I received it!”

Liszt in conversation with Lina Ramann

I

On October 30, 1873, Liszt boarded a train in Rome and crossed the border into Hungary. The train was halted at least twice, first at Esztergom and again at Vác, where local dignitaries waited on the platform to extend their greetings to Liszt. As it drew into Budapest’s main terminus, a group of prominent Hungarians stepped forward to meet the composer as he alighted from his carriage, including his old friend Baron Antal Augusz, the composer Henrik Gobbi, and the sculptor Pál Kugler. What was the purpose of Liszt’s trip? And why was he the object of such a special outpouring of affection on this occasion?

His visit to Hungary had been carefully planned for months. It was a double celebration. First, it marked an important milestone in the history of the nation: the merging of the twin cities of Pest and Buda into the modern capital of Budapest. Some important ceremonies had been arranged to commemorate the event, and it was natural that Hungary’s leading expatriates, among whom Liszt was pre-eminent, should return home for the celebrations. But in Liszt’s case a second, more personal reason prevailed. This homecoming was also intended to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of his public career, which was generally regarded as having begun in Vienna’s Redoutensaal, on April 13, 1823, when he was a boy of eleven, and when, so rumor had it, he had received a Weihekuss, or public “kiss of consecration,” from Beethoven.

Baron Augusz and the others drove Liszt directly to his new apartments at no. 4, Fischplatz, a building that had recently been acquired by the Hungarian government for the purpose of housing the first Royal Hungarian Academy of Music, with Liszt as its president. Four days (November 8 to 11) had been set aside for the Jubilee concerts in Budapest, but other celebrations were planned in nearby Esztergom and Pressburg as well. By far the most important event was the first, uncut performance of Liszt’s oratorio Christus, on November 9, conducted by Hans Richter. On November 23 there would also be a performance of the Gran Mass in Pressburg. Between times, Liszt was expected to attend a grueling round of concerts, recitals, and banquets, many held in his honor.

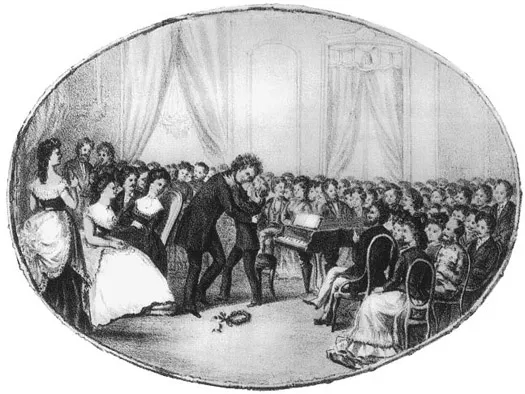

Beethoven embraces the eleven-year-old Liszt at the boy’s “farewell” concert in Vienna, April 13, 1823. (A fictional scene depicted in an 1873 lithograph by István Halász.)

Amid the clamor surrounding this visit, and the festivities within the city generally, an event took place which passed almost unnoticed. A commemorative lithograph was circulated by the publishing house of István Halász; it consisted of a series of tableaux symbolizing events in Liszt’s life. One of these pictures depicted Beethoven embracing the young Liszt at that public concert in Vienna fifty years earlier; Beethoven has advanced toward the piano to place a “kiss of consecration” on the child’s brow. Few people bothered to question the truthfulness of this scene; after all, the legend of the Weihekuss had been in circulation for half a century and Liszt had done nothing to deny it; in fact, he had actively encouraged it. But we can say with certainty that Beethoven never attended this concert. To explain why, we have to go back to the event itself.

II

By April 1823, the Liszt family had been in Vienna for about fourteen months, during which time the boy had received piano lessons almost daily from Carl Czerny. Adam Liszt, the father, was now anxious to present his talented son to the world, and decided to mount a “farewell”concert designed to attract the maximum amount of publicity in the Austrian capital, before he and his son set out for Paris in pursuit of further success abroad. The small Redoutensaal was booked and the concert announced for Sunday, April 13. Adam knew that there was no better way to guarantee a success than inviting Beethoven to attend the concert, and perhaps persuading him to provide a theme on which his son might improvise. The contacts that might make such a plan possible were already in place. Carl Czerny had been a pupil of Beethoven, and through him the necessary approach could be made to Beethoven’s amanuensis Anton Schindler with a request to arrange a meeting with Beethoven. The deaf composer’s Conversation Books do, in fact, contain an authentic record of this visit. It is well known that Schindler tampered with the Conversation Books after they fell into his possession at Beethoven’s death in 1827;this argument is sometimes raised in an attempt to cast doubt on the entire set of entries concerning Liszt, and even on the fact that Liszt and Beethoven met at all. A glance at the entries in question does, in fact, show that Schindler later modified some that concern Liszt. (We have set them in square brackets to indicate that their removal has no bearing on the question of the Weihekuss.)

The following entry was written in the first part of April 1823, a few days before the concert, either in the hand of the young Franz or more likely that of his father:

“I have often expressed the wish to Herr von Schindler to make your high acquaintance, and I rejoice, now, to be able to do so. As I shall give a concert on Sunday the 13th, I most humbly beg you to give me your high presence.”

The days passed, and Adam Liszt must have found the delay frustrating. It is clear that he approached Schindler again. On April 12, the day before the concert, the following series of entries appeared in the Conversation Books, written in Schindler’s hand. Beethoven’s replies were spoken, of course; but by reading between the lines we can infer that his earlier reception of the young Liszt had been less than friendly.

“Little Liszt has urgently requested me humbly to beg you for a theme on which he wishes to improvise at his concert tomorrow. Ergo rogo humilime dominationem Vestram, si placeat scribere unum Thema.”

———

“He will not break the seal till the time comes.”

———

[“The little fellow’s improvisations do not amount to much.”]

———

“The lad is a fine pianist, but, so far as improvisation is concerned, it is far from the truth to say that he really improvises.”

Beethoven did not provide a theme for this concert. We know from a report in the Wiener Allgemeine Musikzeitung (April 26, 1823) that Liszt improvised on twenty-four measures from a ponderous (unidentified) Rondo instead, and that it did not make a particularly favorable impression. The Conversation Books go on:

“Carl Czerny [is his teacher].”

———

“[ Just] eleven years old.”

———

“Do come; it will certainly please Karl to hear how the little fellow plays.”

This reference to “Karl” is to Beethoven’s young nephew. Schindler’s inference is that although Beethoven might take no pleasure in a concert he could not hear, at least Karl himself might enjoy it. As we shall see, later entries in the Conversation Books imply that neither Karl nor Beethoven attended the concert. The entries continue:

[“It is unfortunate that the lad is in Czerny’s hands.”]

———

[“You will make good the rather unfriendly reception of recent date by coming to the little Liszt’s concert.”]

———

[“It will encourage the boy. Promise me to come.”]

Why did Schindler introduce these changes? They were made for self-serving ends, as a result of his ongoing work on Beethoven’s official biography. He wanted this irreplaceable source to “confirm” his own recollection of events, especially where those events, with some suitable adjustments, might present Schindler himself in a more favorable light. As his memories were stirred, he may even have convinced himself that his revisions created a truer historical record. His modifications have been called “forgeries,” but they are not that, because not one of them is in a disguised hand. Nevertheless, Schindler’s work as Beethoven’s biographer is tainted. Where does that leave his comments about Liszt? Not surprisingly, his well-known assertion in his biography (1860, 3rd edition) that Beethoven was not present at Liszt’s concert has been challenged by Liszt scholars, who, generally suspicious of Schindler’s other mistakes, have been anxious to prove that he was. Yet the Conversation Books themselves confirm Beethoven’s absence in an unmistakable way, which has nothing to do with Schindler’s meddling with the historical record. They contain two entries of importance in the second half of April 1823—that is, several days after the concert had taken place. In the first, Beethoven’s nephew Karl tells his uncle that the hall was “not full.” In the second, he again tells Beethoven that someone from the Blöchlinger Institute, a private school in Vienna which Karl was attending, had reported that “the young List [sic] made many mistakes.” It is clear that Karl is referring to an event that neither he nor Beethoven had witnessed—else why would Beethoven need to be told that the hall was “not full”? He may have been deaf, but he was not blind. And although the Vienna press carried reports of the concert, there is not a single mention of Beethoven’s presence, which, in his capacity as Europe’s leading composer, would surely have been headline news.

The story that Beethoven was present at Liszt’s “farewell”concert and had placed a public kiss of consecration on the boy’s brow had first appeared in print in Joseph d’Ortigue’s early biography of Liszt (1835) and had acquired some colorful embellishments along the way. Schilling (1837) even had Beethoven mounting the plat-form, grasping the boy’s hand, and proclaiming him “Artist!” The Halász lithograph, then, was only pictorializing what the printed word had been telling people for years. In 1881, not long after that lithograph appeared, the first volume of Lina Ramann’s authorized biography was published. Ramann’s text not only had Beethoven attending the concert but described him as fixing the boy with his “earnest eye,” a remarkable observation from one who was not even born at the time of the event in question. Later biographers now not only had a picture but an “official” text to go with it (they knew that Liszt had granted Ramann personal interviews to help her with her work, and they therefore assumed that her account of the story of the Weihekuss must have had Liszt’s sanction). Secure in the knowledge that no one was looking, Frederick Corder, in a twentieth-century update of the story, even moved Beethoven to the front row of the concert, presumably out of consideration for the great man’s deafness.

From all the available evidence it seems that scholars have muddled two quite separate incidents: the kiss itself and Beethoven’s attendance at the farewell concert. In the last edition of his Beethoven biography (1860), Anton Schindler categorically denied that Beethoven was present and wrote that, because of his deafness, “Beethoven did not attend this concert or any other private concert after the year 1816.” We quote this part of his text in full:

The author knows of only one occasion on which Beethoven’s reception of a young artist could not be called friendly. The incident has to do with Franz Liszt whom, in the company of his father, I introduced to the master. Beethoven’s lack of cordiality sprang in part from the exaggerat...