![]()

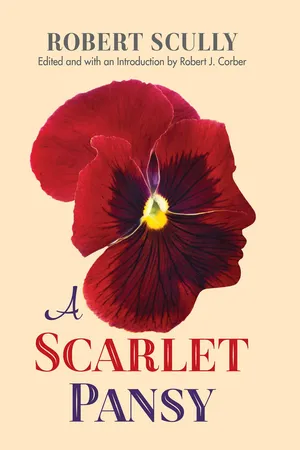

A SCARLET PANSY

by Robert Scully

![]()

1

FAY ETRANGE LAY DYING ON A BATTLEFIELD IN FRANCE, dying in the arms of the man she loved.

Young Lieutenant Frank, much younger than herself, tenderly drew her closer. At that time he did not sense that she had sacrificed her life to save him. Though she had revealed her true self, in his gratitude for her recent ministrations he thought he loved her. Perhaps he did. Perhaps he was even broad-minded enough for that. At least in after years he was heard to speak reverently of Fay.

Fay was beautiful, had always been beautiful, from babyhood onward. Whatever feature is to be admired in a babe, she had possessed: skin of the softness and bloom of a dainty blush rose; eyes of deepest blue; ringlets of spun gold. And later, at the age when growing girls are thin and gangling, she had been pleasantly rounded and winsomely lovely. Even at the time of her death, when she was well past thirty-three, her beauty had not begun to fade, but with each year had seemed to take on an appropriate maturity. Best of all, she had never realized that she possessed beauty. She had studied her mirror but little, except when making up for some grand function. This was due to an overwhelming interest in others and in objects about her, a trait manifested early in life.

Though Fay belonged to the emotional type, nevertheless, she was possessed of a marked interest in science. Thus her life had developed along complex lines.

At the age of five years, Fay had suffered her first sexual trauma, a thing so revolting that she resolutely thrust it from her mind, and it only recurred to her and was vividly recalled in after years when she sought for a full sequential explanation of the development of her dream and love life.

Fay was born in a quaint little white cottage at Kuntzville, in the lower Pennsylvanian hills. Here she lived with her father, mother, two sisters and her brother William. Her parents were of that superior type which in a past generation had been called so proudly “good American stock.”

Her father’s farm was large. In summer the little child roamed freely about the flowered fields and beneath the immense trees of the nearby woods. One rainy day she chanced to run to the barn for shelter. Here, unseen, she discovered two neighbor boys playing at what they conceived to be mannish practices. Fay was fond of the older of the two, and a few days later, meeting him alone in the woods, asked what he and Jack were doing in the barn and told him what she had seen. The boy, Fred, at once sensed the possibility of disgrace from a childish tattler. Raising his fist threateningly, he asked, “Did you tell anybody, anybody a-tall?”

“No, I didn’t tell,” Fay fearfully assured him over and over.

“Then I’m a-goin’ to make you do somethin’ too, so you dassn’t to tell.” He directed. In terror Fay complied.

“Now you’re wusser ’n us,” Fred taunted. “An’ don’t you dast to tell nobody!”

So forceful was he, and so terror stricken was the child, that she never did tell her elders. Later on in life, when she had run across so many people who never knew when to cease babbling, Fay was glad she had learned to keep silent.

Of course psychologists of some schools will insist that this early trauma laid the foundation for all of Fay’s later escapades. Was it that, or was it the constant seeking after an unrealized ideal, an ideal conditioned by some inward physical development not readily discernible through externals? However that may be, her first loves were idealized, and each disillusionment was followed by a sense of keen self-condemnation and by a long period of hopelessness before again attempting to grasp happiness through love. If they later became more frequent and promiscuous, perhaps it was because of the attempt to find in the many a summation of the attributes which love craves.

From the time of her first childish episode at five, until late in adolescence, she had no further frankly sexual experience. She did have frequent “crushes” in her first contacts at school, and these, as with all children, were sometimes directed towards the young, sometimes towards mature people; sometimes towards her own sex, sometimes towards the opposite sex. Aside from her physical beauty, she was always a marked child, never interested in the games of other children, always dreaming, so absorbed with some inner urge that she often seemed stupid to normal children. Yet her school fellows always went to her for advice and sought her out for aid when lessons were difficult.

Fay loved all animal life, human or otherwise; the difference was only in degree, and this motivated her future career. From her mother she inherited a love of service. As much as possible she followed that good woman about on expeditions to nurse sick neighbors, or to render other kindly offices, though the father demanded much of Fay’s time for work in the fields or about the barns.

Early Fay learned to feed the smaller stock and to nurse any sick baby animals. As she developed sturdily, she was obliged to give her time and strength to the rough field work, doing quite as much as her older brother Bill. She would have preferred to be with her mother in the house, doing womanly tasks, cooking, sewing, beautifying the home, but her father resented any such attempts. Thus the instincts that were normal to Fay were somewhat thwarted in her home life.

The years of work, school and play sped by. The village school and the town high school were soon finished. Then the need of earning money was forced upon her. Debt had piled up. The summer after finishing high school, Fay worked side by side with her father and brother Bill, ploughing, planting, harvesting. At sixteen she could pitch as much hay as her father, could plough more land in a day, could lift heavier burdens. She was strong and healthy. But there was that in her cheeks, her eyes, even her hair, that proclaimed her sexually different. Mentally there was a hidden unrest, dimly perceived by her brother Bill, who resented her difference from the common herd and frequently taunted her on her manner of speech or her graceful movement—the antitheses of his boyish ideal.

Fay realized that the farm was not her place. She determined to go to the nearest large city, which happened to be Baltimore, to make her own way at least, and to try to stand as a buffer between her family and the hardships of the world. With Fay, thought was quickly followed by action.

’Twas a dull day in February when Fay left home, left it to return only for such dreary events as family funerals. After the hard summer’s work on her father’s farm, or about the community, doing whatever she could to earn a dollar here or there, harvesting crops, picking fruit, peddling produce of all kinds to the neighboring towns, her efforts had failed to do more than pay her share of the expenses at home and provide a rather scanty cheap wardrobe. The most important thing was that she had learned to work, to work hard, and to be independent of others. So she was off to Baltimore. Money! The family must have money! She must hasten and earn. She could not bear to see her mother becoming more bent and tired-looking, denied many of the necessities and most of the pleasures of existence, for Fay’s affection for her mother colored all of her early life.

The sun was sinking as the train which was to bear Fay away pulled into the station at Kuntzville. Any sentiment she might have called up at this parting was dispelled by the presence of a neighbor’s boy, who was going to the nearest small town to take a job, and attached himself to her. They sat together on the train. He urged her to stop in the town where he was going and to attend a theatre and afterwards go to a dance hall, explaining in great detail how “a fellow can pick up a girl.” But Fay’s mind was on essentials. At the railway junction they parted.

Fay had to wait an hour for the Baltimore express. A dowdy old woman sat beside her, asked, “Where you goin’? How long you got to wait?” and finding that the wait was ample, started out to sing a saga of the family Ritter. Once Fay interrupted to get a drink of water. On her way to the cooler she observed a well-dressed man looking at her intently. It was but a moment before he was at her side offering assistance, seeking to engage her in conversation. She sensed something wrong about him. Perhaps he was a pickpocket! But he was not a pickpocket. Fay hurried back to the old woman. This first meeting with a strange man was almost prophetic. For the rest of her life she was to meet his kind, wherever and whenever she travelled—always seeking her and the favors she could bestow.

At last the Baltimore express arrived, and Fay and her small packages were stowed into half of the seat of a day coach. The car was dimly lighted by gas. Every seat was filled, and it seemed to Fay that each occupant was possessed of a distinct and repellent odor. All of them were untidy and most of them more or less dirty. Fay felt a sensitive recoil, which but accentuated the loneliness that was beginning to well up within her.

The train jerked along. Fay alternately waked and dozed and dreamed horrible dreams. At dawn they dragged into the suburbs of Baltimore. There was no snow, but the ground was bare and frozen; the air was smoke-befouled and the landscape dreary; it all formed an unpleasant contrast to the clean wintry aspect of her snowclad Pennsylvania hills. When she alighted from the train she felt a damp chill which was more penetrating than the dry cold of the higher country. She left the railway station and looked about her. Already the sun, which at peep of day had promised gay sunshine, was beginning to be obscured by a dull grey fogginess, bringing twilight at early morn.

The city was bewildering.

For several blocks Fay could see only warehouses, freight stations and horse-drawn drays going back and forth. A long way up the street, and in the direction which most of the travelers pursued, higher buildings were in evidence. She reasoned that there she would more likely find a stopping place. As she started forward, a policeman who had observed her hesitancy stepped up and asked, “What’s botherin’ you? Don’t you know the town?”

“I would like to find a place to board,” she explained in her too musical singing type of voice.

At once he was all kindness and waved his stick in the direction of a spire with the admonition “Keep that thar spire in sight and right besides it you’ll come to the Y. There they c’n tell you of plenty places.”

Fay picked up her suitcase and started forward, while the cop muttered to himself, “Nice lookin’ youngster. Nice lookin’ country youngster.”

How disagreeable the air was to Fay! Those were the days of horses, and all cities reeked of the odor of equine effluvia. Then too, sanitation in general was not so good as today. In the poorer parts of towns a smell of horse, sewage and garbage prevailed.

Fay picked her way carefully across the street and onwards toward the spire that was to be as a beacon to her for the next year. She arrived at the Y, a building of brick with a low, arched doorway placarded, “You are welcome.” Fay smiled. She entered and approached the nearest desk. The professional welcomer arose and initiated her to the usual overly ardent handclasp. Questioning, he learned her mission and piloted her to an official for enrollment as a new prospect of the Christian welfare workers of the city to guard and watch over, and, if possible, bring into the fold of the righteous.

The official was a thin, wrinkled, sallow, sandy Scotsman, bent and spectacled, half-bald, a man of about thirty-five, of the type Fay later learned to classify as “born old.” He greeted Fay effusively: “We are pleased to welcome you to our midst. You refreshing young country people, you buoyant adolescents who bring an air of health and verve with you! Our cities would decay unless they were replenished and constantly rebuilt by the fair youth of the countryside.” Fay listened with amazement. Much useless language was an unfamiliar thing to her. Sandy was very flattering and patted her arm. Then he gave her a list of boarding houses “on the approved list,” and spoke gushingly of the hope of seeing her again and the hope that she would avail herself of some of their night classes. Night classes! The very thing she had hoped for! There was no fee for finding her a boarding house but there was a fee for filing with the employment agency. She learned, too, that there were other employment agencies, and with anxiety also learned that a young person who is without specific training in some one branch of work “is very difficult to place.”

Fay found a boarding house, a dark, dingy, ugly house, not too clean, situated on a street which was still respectable but which abutted on the edge of the less reputable part of the city. The landlady was a small dark Virginian of lovely manners but of shabby attire. Fay noticed the unaired smell of the house as she was guided to her room on the top floor. The room had one window, and that opened on an airshaft; there was a shade but no curtain. There was a small bed, a washstand with a tarnished-looking bowl and pitcher, and a single chair. She was instructed that when she needed better light to turn on the gas. The landlady illustrated. The sickly flicker seemed to add to rather than to dispel the dreariness of the dimly lighted room. The linen, though recently washed, looked grey and unclean. The carpet was spotted and dirty. The room’s one virtue was extreme cheapness. The landlady quickly recounted the advantages of her house and its location and added a brief description of the good companions whom Fay would find there; these included “a splendid young man from the Eastern Shore”; a farmerpolitician who was a member of the legislature; a wonderful young man who was a sewing machine agent; Mr. Strong, who was a boss carpenter (and, incidentally, the lady’s secret lover, as Fay later learned); and Mr. Shorthorn, who was a motorman. Fay would meet them all at the evening meal. Meantime, she could pay a week in advance and make herself at home. “At home!” Already she loathed this place, as she was to loathe all of her city dwellings for the next five years to come—cheap, dirty, depressing. The landlady was all kindness. Truth to tell, generosity had and always would be her undoing. She gave shelter and food to those who failed to pay; she gave love to those who used it and failed to reciprocate. She looked at Fay with pity and sympathy. So many had she seen come to the city, only to be transformed into hardened, selfish human animals. To Fay’s anxious inquiry about prospects for work, the lady assured her: “No one who wants work will fail to find a job.” She cited case after case of her young men who were “successes,” young men who had come from the country and taken positions in offices and factories and in a brief two or three years become head bookkeepers or chief clerks or foremen of departments—and gone to live elsewhere. She ended, “Yes, indeed, you will find work and success.”

It was to be but a brief time before Fay would forget that Mrs. Foreman was a slattern and incompetent and remember only that she was the embodiment of generosity. Later in life, when Mrs. Foreman’s bright prophecies of success had in some degree been realized, Fay was to meet the cream of American society and titled Europeans aplenty; but never did she meet one who was always such a perfect exemplification of kindliness and good manners as was this little dark Virginia woman.

At the evening meal, Fay met the assembled paying guests. She listened to them, avid to learn. Years later she could recall that supper of ham, cabbage, corn pone and talk, much talk, and afterwards a banjo badly played, and games of euchre before a pungent-smelling soft coal fire in an open grate in the “parlor.”

At bedtime Fay counted her depleted hoard, which had shrunken to less than ten dollars.

![]()

2

To ANYONE WHO HAS EVER BEEN STRANDED IN A STRANGE CITY, this part of Fay’s life would seem familiar. Her second day she made three rounds of the Y, the employment agencies and every shop and office within a certain district of the city. The third day was like unto the second, with the exception that she invaded the blocks adjacent. The fourth and all the days up to the end of two weeks were the same, and still there was no work offered to her. Hope steadily sank. Her lovely face became drawn and pale from terror. The landlady had not yet asked her for another week’s rent. The beginning of the third week was at hand. She had scarcely tasted food, feeling that she had no right to eat that for which she could not pay. She hurried from the house. It was her lucky day. At her third call, a coal dealer told her he would give her work. He looked at her closely and seemed to sense that she was in dire need of employment. Fay could never decide whether pity or the desire to take advantage of her necessity induced Mr. Rush to give her a job. But she was thankful for an opportunity to labor, even at the pittance offered her, which allowed a margin of fifty cents each week after all expenses were paid. At once she took her place in the line of laborers. In those days all coal was handled by means of shovels and barrows. For Fay was young an...