![]()

1

Building (and Not Building) New York City’s Subway System

Robert A. Van Wyck, the first mayor of the Greater City of New York, broke ground for the first subway line, near City Hall, on March 24, 1900. George B. McClellan, the third mayor of the five boroughs, officiated at its opening on October 27, 1904. It took four years, seven months, and three days to build the line from City Hall to West 145th Street in Harlem.

Things rarely went that quickly again. The New York Times article about the groundbreaking spoke of building extensions to areas like Staten Island “before this town is very much older.”1 It wasn’t the first time, and definitely not the last, that a promise to expand the subway system went unfulfilled. More than a century later, Staten Island still awaits subway service.

For as long as there have been plans for a subway system, people have wanted to build it farther—to the city’s limits and beyond. In some cases, their efforts have resulted in lines being built; other ambitions went unfulfilled. Some plans will soon achieve a degree of success after decades of failure.

A series of agencies were responsible for planning the growth and development of the subway system in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

The first was the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners (RTC), created in 1894. As work on the first subway line was underway, the RTC considered the next steps to expand the system. On May 9, 1902, RTC President Alexander E. Orr wrote to Chief Engineer William Barclay Parsons, instructing him to begin “the preparation of a general and far-reaching system of rapid transit covering the whole City of New York in all its five boroughs.”2 Parsons developed proposals for expanding the system into Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens during 1903 and 1904. Parsons resigned on December 31, 1904; an overall plan was released on March 30, 1905. His successor, George S. Rice, prepared a second plan, which was released on May 12.

The RTC was responsible only for planning the lines. The responsibility for operation rested with another agency, the State Board of Railroad Commissioners. Governor Charles Evans Hughes3 wanted one agency to regulate public transit, railroads, and all other public utilities. Despite protests that local authority was being abrogated, Hughes signed a law sponsored by State Senator Alfred R. Page and Assembly Member Edwin A. Merritt on June 7, 1907, creating the New York State Public Service Commission (PSC). The legislation split the state into two PSC districts: the first consisted of New York City’s five boroughs, and the second the rest of the state. The RTC’s last act was approving construction of Brooklyn’s 4th Avenue line from downtown Brooklyn to Sunset Park on June 27.

There were doubts about the PSC. “The public has heard so much of the Utilities Commission that it expects the impossible,” the New York Times quoted an unidentified expert on transit issues saying a few weeks after they came into existence. “I believe that the new board will come in for quite a good deal of criticism before it accomplishes anything, but this does not mean that the Commissioners are at fault. If in two years the commission has improved the rush hour service on the various lines to any marked extent, it will have accomplished a great deal. The best it can do in the next few months will be to improve the midday, Theatre hour, and early morning service.”4

The 4th Avenue line was included in a proposal made to the RTC by Brooklyn Borough President Bird S. Coler in 1906. He called for a line to be built from Pelham Bay Park to Fort Hamilton and Coney Island, running along Westchester Avenue, Southern Boulevard, and 138th Street in the Bronx, 3rd Avenue and the Bowery in Manhattan, and Flatbush Avenue and 4th Avenue in Brooklyn after crossing the Manhattan Bridge. A branch would run to Coney Island via 40th Street, New Utrecht Avenue, 86th Street, and Stillwell Avenue.5 The New York Board of Transportation would use this concept four decades later in plans for the 2nd Avenue Trunk Line. In 1906 this was the start of what would eventually become the first major expansion of the subway system.

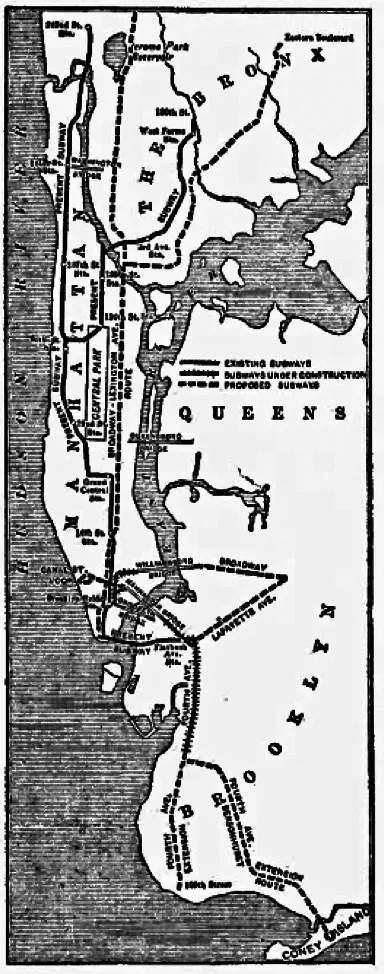

Rice expanded on Coler’s proposal, proposing that ten new subway lines be built to serve Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn by 1916. Rice thought that Queens would be well served by trolley service through the Belmont Tunnel, then approaching completion (but not put into service for eight years as a subway tunnel, used by the Flushing line), and over the Blackwell Island’s Bridge, which would open in 1909 as the Queensboro Bridge.6 This led to the release of the PSC’s first major plan, the Tri-Borough Plan.

The heart of that plan was the Broadway–Lexington Avenue line, running from the Battery to Woodlawn and Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx. The Tri-Borough Plan would begin to build toward subsequent plans, containing elements of the Lexington Avenue, Broadway, Jerome Avenue, Pelham, 4th Avenue, West End, and Brooklyn–Queens Crosstown lines.

The Tri-Borough Plan was not well received. The Flatbush Taxpayers Association protested the lack of a Nostrand Avenue line.7 The Queens Borough Transit Conference protested that its borough had been ignored. “We will resort to the courts if necessary if Mayor [William Jay] Gaynor and the Board of Estimate and the Public Service Commission insist on developing the outlying sections of Brooklyn and the Bronx at the expense of Queens,” said the Conference Chairman, James J. O’Brien.8

Figure 1-1. The routes of the Tri-Borough Plan. (Queens Borough Chamber of Commerce)

Mayor Gaynor had qualms. The PSC wanted the Tri-Borough Plan lines built as a system independent of the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit Company) and the BRT (Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company). Gaynor wanted to base the subway system’s expansion on extensions of existing lines. This difference in philosophy lasted for years and affected the Tri-Borough Plan. When the time came to open bids for constructing and operating its lines, the PSC found that no one submitted offers. Moreover, the IRT and BRT appeared to be dragging their heels on extending their lines.

It wasn’t until William Gibbs McAdoo sought to link the Tri-Borough routes with his Hudson and Manhattan Railroad system and further expand them9 that the IRT and BRT considered expansion. In January 1911, a committee from the Board of Estimate consisting of Manhattan Borough President George A. McAneny, Bronx Borough President Cyrus C. Miller, and Staten Island Borough President George Cromwell met with the PSC and began the process that led to the issuance of the Dual Systems Contracts in 1913.

The IRT and BRT maneuvered back and forth to gain authorization to operate the lines that the Committee and the PSC were considering, offering to operate all or many of the new lines. Both companies staged PR campaigns to gain favor with both the general public and elected officials.

When the PSC approved the Dual Systems Contracts in March 1913, plans to extend service to northeast Queens, Staten Island, and along Utica Avenue in Brooklyn were deferred—permanently, as events turned out. Construction of the Crosstown line, a north–south route between Brooklyn and Queens proposed by the BRT was postponed for more than a decade; when work began, it was part of a transit system operated by the Independent City-Owned Subway System (IND). Lower-level platforms and connecting tunnels that had been built at the IRT’s Nevins Street station in anticipation of that company being awarded the franchise for 4th Avenue line (along with the tracks running over the Manhattan Bridge and along Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn) have sat unused by trains for more than a century.

Nonetheless, the lines built under the Dual Systems Contracts represented the single biggest extension of the subway system to that point. The IRT would stretch farther out into the Bronx and well into Queens and Brooklyn. The BRT (later to become the BMT) would rebuild the lines they were operating in Brooklyn, expand farther into that borough and Manhattan, and extend into Queens.

However, the PSC was still viewed as slow and cumbersome, as it had functions and responsibilities beyond the transit system. In 1919, the doubts that had been expressed when the PSC took control over the transit system were still being discussed. Questions were raised as to how their operations could be streamlined. One person who thought he had an answer was New York’s new governor, Alfred E. Smith. In his inaugural message Smith called for change:

There is widespread dissatisfaction, particularly in New York City, with the Public Service Commission.

In the First District, a radical change should be made in the structure of the commission itself if it is to accomplish results. At the time of its formation in [1907] there was expressed grave doubt as to whether or not it would work out well. There were many who believed that the function of constructing rapid transit railroads for the City of New York should be divorced from the function of regulating public utility corporations generally. In my opinion experience has demonstrated that they were right.

For years the trend in New York City, as well as in the state, has been towards single headed commissions to the end that the responsibility may be fixed upon one man. During the recent war the Federal Government taught us the lesson that results may be best obtained by a single executive clothed with proper power when any great work is to be carried out successfully.10

Smith signed the legislation creating the position of transit construction commissioner on May 3, 1919, offering the post to William Barclay Parsons, then serving with the army in France; Parsons declined. Smith turned to New York City’s commissioner of plants and structures, John Hanlon Delaney.

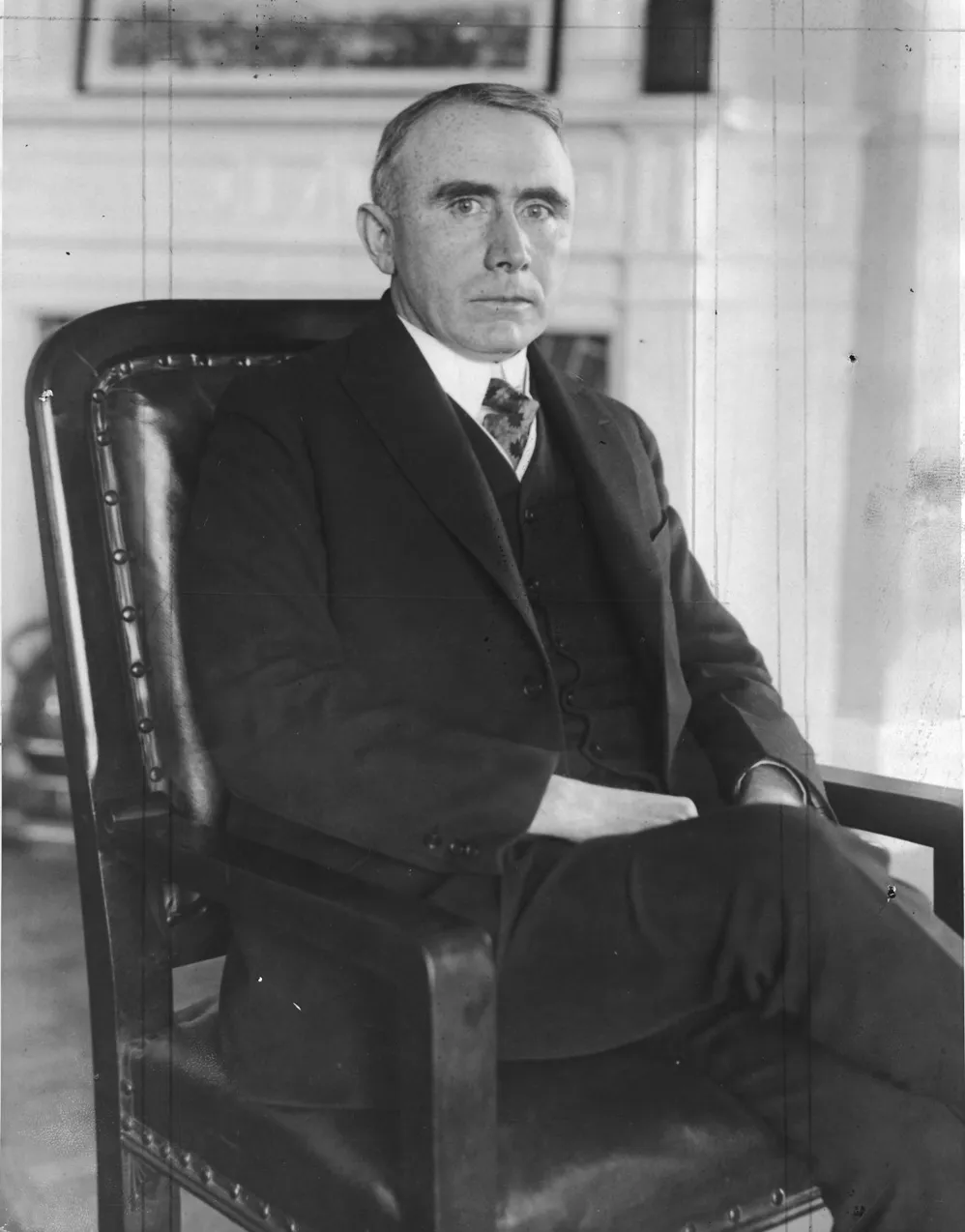

Delaney is not well remembered today, but he was the dominant figure in the New York City transit system for twenty-five years. He grew up in North Adams, Massachusetts, working in the printing trades, and came to New York in 1892. In less than a decade, Delaney became the president of the Printers’ Union and then moved into management. In 1913, Governor William Sulzer asked him to serve in the New York State government as an efficiency expert. Mayor John F. Hylan appointed Delaney commissioner of plants and structures in 1918. A year later, he became transit construction commissioner, supervising the construction of the subway system, with Smith promising a more hands-on approach to advancing transit capital programs.

Figure 1-2. John H. Delaney in 1928. (Photo courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island Division, Chamber of Commerce of the Borough of Queens Records)

John Delaney was a political insider who developed a strong knowledge of transit issues. More than two decades before the consolidation of the subway system, he saw the virtues of unification.11 In 1921, the New York Times wrote that Delaney “worked in accord with the Board of Estimate and with all of the influential Democrats in the city. Much of his time in office was occupied in studying the transit problem, and he was soon recognized as an expert on the subject. He gets along famously with the traction [subway] officials as well as with the city officials, and it was understood that his plan for solving the traction problem was the practical solution of the matter.”12

Delaney appointed Daniel Lawrence Turner, another major figure in the history of the subway system, to the position of chief engineer. He had worked for the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners and the PSC as the original parts of the subway system were being built. He followed Delaney to the Board of Transportation and would later work with the New York State Transit Commission, the North Jersey Transit Commission, and the Suburban Transit Engineering Board. H...