![]()

1 Ice, Air, and Crowd Poison

It didn’t matter that it was a gala performance of a hit show. The weather wasn’t going to cooperate.

The newly renovated Madison Square Theatre had opened in February 1880 with the melodrama Hazel Kirke. A tearjerker and a particularly slushy one, it somehow had captured the fancy of the theatergoing public and was heading for a record run. But in late May, as the Madison Square’s management was busy advertising the play’s upcoming one-hundredth performance, the Northeast was gripped by a freak hot spell, with several days of temperatures topping out in the mid-’90s. Slangcrazy New York had only recently come up with a new catchphrase, a remake of an old scientific term, to describe this situation: a “heat wave.” Whatever it might be called, it was guaranteed to make that hundredth performance miserable.

During those years, America was realizing that a heat wave was much more unpleasant in cities than in rural areas: the larger the city, the more brick and stone and human bodies, the more hellishly hot it felt. And New York might be the nation’s largest, richest, and most cosmopolitan northern city, but in reality its latitude was more nearly equivalent to that of Madrid. As often as not, its summer heat could be ferocious. Natives knew this. Tourists were frequently surprised.

Visitors flocked to see Manhattan’s “skyscrapers” (another new catchphrase) and were dismayed to find those looming buildings so badly designed and so closely packed together that breezes were rare and upper floors were like ovens. They trotted up and down Fifth Avenue, gawking at the sumptuous mansions of the wealthy; had they been permitted to enter, they would have found the air inside those homes as hot, heavy, and oppressive as the atmosphere inside any slum tenement. They had heard about the exciting crowds to be found in the cobblestone streets … but the stones themselves absorbed the burning temperatures of the daylight hours, remaining hot well after midnight, bathing pedestrians in stifling heat (and treating them as well to a dose of the city’s signature aroma: a blend of garbage and horse dung). They might see stylishly dressed Manhattanites out and about. A closer look would reveal those sophisticates to be red-faced, panting, and unsophisticatedly drenched in sweat. It was considered impolite to notice.

In New York or anywhere else, if it was hot outdoors, it was going to be even hotter indoors. Should a trip to the theater be involved, this meant that the performance would be a memorable experience—unhappily memorable, as the most wretched part of a torturous evening. In the nineteenth century, summer heat was a problem that the vast majority of architects hadn’t quite learned how to handle; “ventilation” was the fanciest antidote they could offer. And when it came to theaters, ventilation was practically nonexistent. Since Voltaire’s time, the average theater had been designed as a pressure-cooker: windowless (to kill outside light and sound) and swathed in velvets and brocades (to impress the audience), a place in which large numbers of people were forced to sit close together for hours, generating their own considerable bodily heat, without so much as a breeze. Of course audience members would become miserably overheated. There seemed to be nothing to do about it.

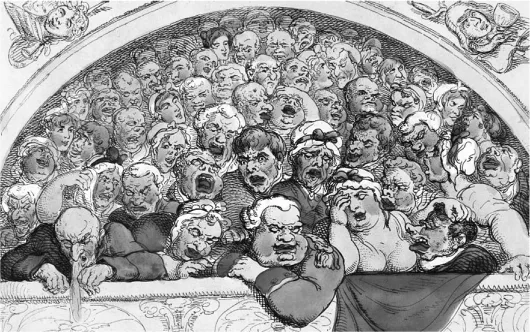

Overheated theaters had been an ongoing problem through the centuries, and it got worse the higher one sat. The famous English caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson offered his own take on the close-packed, sweltering “gallery gods” who toughed it out at the uppermost reaches of Covent Garden. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

For that matter, anyone who felt overheated by the crowding could count on being even more overheated by the lighting. In that pre-electric age, a theater might use a thousand gas jets—on the stage, lined up at the footlights, ranged along the auditorium walls and clustered in the central chandelier—each one a small fire, sucking oxygen from the air while replacing it with carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, even a dash of ammonia. All of those fires effortlessly pushed the temperature to 100 degrees or higher.

Above the chandelier was the single attempt at temperature control: a ventilator, described by one theatrical insider as “a large circular grating, placed in the centre of the roof.” Theoretically, the heat of the chandelier would draw the auditorium’s hot air out through the ventilator. It was a system that was almost guaranteed not to work. The indoor air became “vitiated,” the polite term for an atmosphere that was oxygen-starved, fouled with nauseating gases, unbreathably hot. And a whole evening of vitiated air was a sickening experience. Men who braved the theater under those conditions steeled themselves for a night of piercing headaches, with clothing completely soaked from their woolen underwear all the way out to their coats. Women, crushed into their corsets, tended to faint from the heat. Or perhaps they would slip out to the ladies’ lounge in order to vomit in privacy.

Like it or not, suffering from the heat was a part of summer playgoing. The Courier and Enquirer had once called it “a two hours seething with four thousand mortal men and women in a huge cauldron of brick and mortar.” The humorist Thomas Hood had gone into even more unappetizing detail, describing the genteel horror of sitting through a play in hot weather:

What a scene of general relaxation! The “perspiration of delight” … stands upon every forehead; handkerchiefs, as signals of distress, are flagging with their owners in all directions; curls, unwinding into lankness like cotton balls; and collars curling off from the obnoxious glowing cheek, like the leaves of the American sensitive plant. The thin pale gentleman on our right looks cool, but he is only at a white heat.… That stout lady’s visage in the left-hand box might pass for Aurora’s,—intensely rosy,—and a leash of pearls—(are they not?)—escaped, perhaps, from her tiara, are stealing down her brow.… [W]e think the simple glare of the lamps might have accounted of themselves for the head-splitting symptoms of the playgoer.1

A majority of New York theatrical managers had learned simply to call a halt during the hottest months, closing their shows until cooler weather arrived. But this performance of Hazel Kirke was taking place in May, not in July or August. Everyone understood that midsummer theatergoing was out-and-out masochism; theatergoing in the late spring was more of a game of roulette, a bet against the weather. Once the thermometer had started climbing, this audience had lost the bet. On the night of the one-hundredth performance, playgoers entered the doors of the Madison Square Theatre with grim, set expressions, wishing they were anywhere else.

However, as they stepped from the lobby into the auditorium, they were in for a shock. The streets were registering a temperature above 90 degrees—but the temperature inside the building, astonishingly, was an invigorating 70 degrees. One audience member was the English novelist Mary Duffus Hardy, who had equipped herself for the worst with smelling salts as well as a fan. But she discovered that she didn’t need them:

Immediately on entering, we felt as though we had left the hot world to scorch and dry up outside, while we were enjoying a soft summer breeze within. Where did it come from? The house was crowded—there was not standing-room for a broomstick; but the air was as cool and refreshing as though it had blown over a bank of spring violets.2

As men stopped mopping their faces and women put away their fans, they looked around in confusion. A theater in summer weather wasn’t supposed to be endurable, let alone comfortable. But a note in the program explained it in a single line:

COOLED WITH ICE

It was one of the first times people had experienced a ventilation system that attempted to cool the air specifically for their comfort. More to the point, this was one of the first times that such a system really and truly worked. And it was a sensation.

The Madison Square Theatre instantly became a must-see attraction for New York natives as well as tourists. As for Hazel Kirke, it was able to ignore the thermometer and run straight through the summer, shattering Broadway attendance records in the process. But the exact reason for the show’s popularity escaped no one. One man told a reporter that he was seeing the play for the twelfth time: “Certainly I like the play … but between ourselves, we all know it by heart now, and make up family parties to come here and be cool. It is the coolest spot short of Coney Island to spend an evening.…”

“Cooling Devices … Are Not Attainable”

There had always been a strange mindset when it came to extremes of weather. On the one hand, cold was regarded with deadly seriousness. From the beginning of civilized time, the poorest peasant had tried to keep a fire burning in his hut. Buildings with stoves or central heating, innovations that caught on in the early nineteenth century, blasted forth hot air without restraint; when Charles Dickens visited the United States, he complained bitterly about the intense, dry heat “whose breath would blight the purest air under Heaven.” Come winter, the average person’s clothing, already heavy, was fortified with an array of still-heavier outer garments. “Draughts” were terrifying things, strongly believed to be carriers of disease, and the slightest threat of “catching a chill” sent most people racing for medical help. An essay of the period illustrated most people’s fears in the bleakness of its title: “Winter an Emblem of Death.”

Heat, on the other hand, seemed to be merely a nuisance, something to be ignored—or greeted with giddy humor. In August 1822 the Charleston Mercury printed an editorial, “Hot Weather”:

It is impossible to write coolly upon any thing, when the thermometer points day after day above 90.… The very juxtaposition of the parts of the body is uncomfortable. One would be more easy if he could separate his limbs from his trunk and put them bye, for a time, in the coolest spot he could find. You may observe how this feeling operates by the frequent raising of the arms from the sides, thus giving an opening for the breeze to fan the heated parts.…

Fat people seem in this torrid season to melt, and lean ones look as if they would dry up.

The heat of the day is followed by that of the night. Cooling devices and anticalorics that would refrigerate the sleeper and the sleepy are not attainable by human art.3

The editorial did what innumerable other writings did and would continue to do for decades: whine about the high temperature while combining stiff-upper-lip fatalism with comic helplessness. And it complained that the miraculous Industrial Revolution had failed to come up with a single machine that could do anything about the heat.

In those early years, there were few options. People living in the country escaped to the outdoors in hopes of a breeze. City dwellers had to adapt. Lower-income people were restricted to the streets, the docks, any available patch of grass, or their roofs. The well-to-do made a point of leaving town. If they were stuck in town, they could retreat to “pleasure gardens,” often some of the few green spots in a city, where there was the promise of cooler air. Better still, there was ice cream; at a time when iceboxes were brand-new and extravagant innovations, any refrigerated food was a lavish treat indeed. Even a simple carbonated beverage was a specialty item. Through much of the century, Lynch and Clarke’s “sodawater” shop at 25½ Wall Street was a magnet for any person who found himself in New York during the summer. Displayed prominently in front of the store was a large thermometer (in those pre–Weather Bureau days it was one of the few reliable thermometers in the city, trustworthy enough that most city newspapers used it as their go-to source for weather reports). On hot days, the climbing temperature readings served as their own form of advertising; without fail, by noontime there would be a line of parched businessmen snaking down the block, each one impatient for an ice-cooled refresher.

Very little had changed by the time that another anonymous wit, driven frantic by the relentless summer of 1856, wrote nonsensically in the New York Daily Times:

Drop an iceberg into the crater of Popocatapetl, fill up with claret, add one of the West India islands to sweeten and flavor; then hand us the tower at Pisa to suck the liquid through, and you will oblige us considerably. Nothing less than this can cool our cracking throat, we do assure you.

There is a thermometer hanging over the way. We have taken the trouble of suspending it opposite to a picture of the Arctic regions, and keep a boy continually holding an umbrella over its head—still it stands several thousand degrees above white heat. The thin red column of colored alcohol glows like the essence of fire; rays of flame seem to burst from the little globe at the bottom and burn into our brain. Whatever the heat may be, that thermometer is always hotter. It is a demon thermometer, and is doubtless filled with some charmed blood gathered from the veins of an attorney at the Witches’ Sabbath.… If we were at this moment to be suddenly iced, we feel convinced that it would be possible to run us into a mould, flavor us with vanilla, and put us on a supper table. Perhaps—ecstatic thought!—perhaps even the loveliest of her sex might take a spoonful of us to cool her beautiful but fevered lips!4

When indoor rooms became too stifling to endure, many city dwellers—forbidden by law to sleep in any park—headed to their rooftops. But each hot night was followed by the next day’s reports of sleepers who had rolled off and plunged to their deaths. (New York Public Library, Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection)

Whether such asininities were printed in the Daily Times or anywhere else, readers didn’t seem to find it strange that they often appeared on the same page as other articles which impassively listed each day’s heat prostrations and fatalities, arranged in neat columns: “Manhattan and Bronx—Dead. Brooklyn—Dead.” For added effect, those articles would carefully note the precise locations at which people had collapsed (in New York, the large stone plaza in front of City Hall was considered a particularly lethal spot; in Philadelphia, the Navy Yard). And many newspapers would publish temperature readings taken in full sunlight as well as in shade in order to provide their readers with the most thrillingly horrific numbers. Some of those articles reported temperatures that ranged up to 135 degrees.

It might seem that the physical dangers of heat just weren’t taken seriously. That was part of it, but the real problem was that those dangers weren’t at all understood. Newspaper editorials might rail furiously against “abominable dark inner offices” and homes in which “inmates stifle in a stagnant atmosphere”; still, the majority of buildings, public or private, were designed without any real attempt to provide ventilation.

The prime offenders were commercial and public structures. Factories in particular had been built with an eye to profit, not comfort, and rarely with a thought to employee well-being. Windows were there for light rather than for airflow. The buildings themselves were crammed with machinery, driven by steam engines, that threw its own massive heat into the air along with various types of debris. The oppressive temperature (one medical commissioner stood among the workers with a thermometer and recorded 140 degrees) and its accompanying odor were favorite topics of horrified observers: “Factory work is by no means healthy. The rooms are heated to an unnatural degree”; “They labour in an over-heated atmosphere”; “The general atmosphere of the rooms is hot, moist, steamy, and disagreeable”; “What numbers of them are still tethered to their toil, confined in heated rooms, bathed in perspiration … ” . But the aristocratic commentator Mrs. Frances Trollope was philosophical: “[I]t is difficult to find any factory properly ventilated—free admission of air being injurious to many of the processes carried on in them.”

The most public buildings of all, houses of worship, were in their way as badly ventilated as theaters; they prided themselves on their elaborate fields of stained glass, but few of those windows could actually be opened.

They weren’t known as “sweatshops” for nothing. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

The Harvard Magazine tried to treat the problem as light comedy in 1863, discussing the famously suffocating atmosphere of the university’s Appleton Chapel: “Indeed, the air is almost as much a part of the building as the walls. Perhaps, from its long residence in the Chapel, it has become, in some degree, sacred and inviolable.… On Sunday morning...