- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mao's China and the Cold War

About this book

This comprehensive study of China’s Cold War experience reveals the crucial role Beijing played in shaping the orientation of the global Cold War and the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The success of China’s Communist revolution in 1949 set the stage, Chen says. The Korean War, the Taiwan Strait crises, and the Vietnam War — all of which involved China as a central actor — represented the only major “hot” conflicts during the Cold War period, making East Asia the main battlefield of the Cold War, while creating conditions to prevent the two superpowers from engaging in a direct military showdown. Beijing’s split with Moscow and rapprochement with Washington fundamentally transformed the international balance of power, argues Chen, eventually leading to the end of the Cold War with the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the decline of international communism.

Based on sources that include recently declassified Chinese documents, the book offers pathbreaking insights into the course and outcome of the Cold War.

The success of China’s Communist revolution in 1949 set the stage, Chen says. The Korean War, the Taiwan Strait crises, and the Vietnam War — all of which involved China as a central actor — represented the only major “hot” conflicts during the Cold War period, making East Asia the main battlefield of the Cold War, while creating conditions to prevent the two superpowers from engaging in a direct military showdown. Beijing’s split with Moscow and rapprochement with Washington fundamentally transformed the international balance of power, argues Chen, eventually leading to the end of the Cold War with the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the decline of international communism.

Based on sources that include recently declassified Chinese documents, the book offers pathbreaking insights into the course and outcome of the Cold War.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR AND THE RISE OF THE COLD WAR IN EAST ASIA, 1945–1946

Jiang Jieshi claims that there never exist two suns in the heaven, and there should never be two masters on the earth. I do not believe him. I am going to make another sun appear in the heaven for him to see.

—Mao Zedong (1946)

—Mao Zedong (1946)

The diversification of power did more to shape the course of the Cold War than did the balancing of power.

—John Lewis Gaddis

—John Lewis Gaddis

China’s “War of Resistance against Japan” ended in August 1945 when Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. Peace, however, did not come to China’s war-torn land. Almost immediately after Japan’s defeat, in the context of the emerging global confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union, the long-accumulated tensions between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Nationalist Party, or Guomindang (GMD), intensified, bringing the country to the verge of another civil war. From late 1945 to early 1946, the Communists and Nationalists, with the mediation and intervention of the United States and the Soviet Union, conducted a series of negotiations on different levels to solve the problems between them, but they failed to reach an overall agreement that would allow peace to prevail. By mid-1946, a nationwide civil war finally erupted, which resulted in the victory of the Chinese Communist revolution in 1949. From an international perspective, the CCP-GMD confrontation intensified the conflict between the two superpowers, thus contributing to the escalation and, eventually, crystallization of the Cold War in East Asia. An examination of China’s transition from the anti-Japanese war to a revolutionary civil war in 1945–46 thus will shed new light on a crucial juncture in the development of the Chinese revolution, as well as offer fresh insights into the connections between China’s internal development and the origins of the Cold War. This will be the focus of discussion of this chapter.

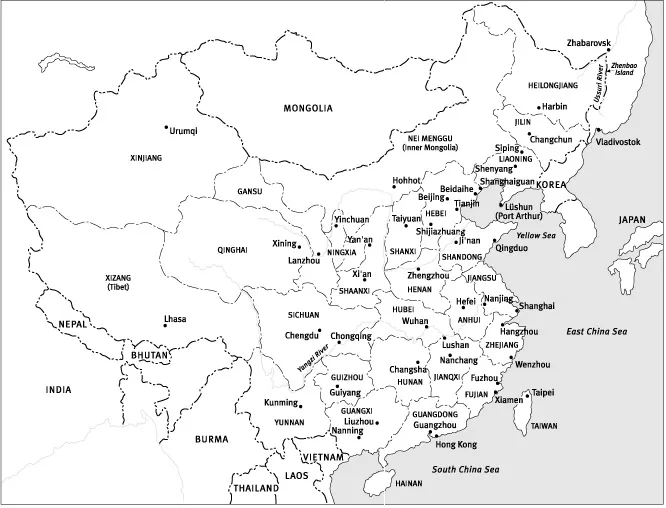

CHINA

The Origins of the CCP-GMD Confrontation

China’s movement toward a civil war began in 1945–46, when the profound hostilities between the Communists and the Nationalists that had accumulated during the war years reached a climax. Given the deep historical origins of the tensions between the two parties, indeed, civil war was almost inevitable.

In retrospect, Japan’s invasion of China in the 1930s changed decisively the course of China’s internal development. From 1927, after the success of the anti-Communist coup in Shanghai led by Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek), to 1936, when the Xi’an incident occurred, the GMD and the CCP were engaged in a bloody civil war. The Communists established revolutionary base areas in the countryside (especially in the South) to wage a “land revolution.” While making every effort to suppress the Communist rebellion, Jiang’s government encountered a series of difficulties from the outset. In particular, Jiang’s leadership role within the GMD needed to be consolidated and the anti-Jiang provincial warlords had to be dealt with. But Jiang’s biggest dilemma emerged after September 1931, when Japan occupied China’s Northeast (Manchuria) and continued to put pressure on the Chinese government through its intrusion into North China. Jiang had to decide who should be treated as his primary enemy—the Japanese or the CCP. Perceiving that “the Japanese were the disease of the skin and the Communists were the threat to the heart,” Jiang risked losing his status as China’s national leader to focus his efforts on suppressing the CCP and the Red Army.1 By 1936, this strategy looked promising: under Jiang’s military pressure, the CCP gave up its main base area in Jiangxi province in the South, to endure the “Long March” (during which the Chinese Red Army lost 90 percent of its strength), and was restricted to a small, barren area in northern Shaanxi province in northwestern China.2 However, Jiang underestimated the impact Japan’s continuous aggression in China had on Chinese national consciousness and popular mentality. In December 1936, Zhang Xueliang and Yang Fucheng, two of Jiang’s generals who opposed his policy of “putting the suppression of the CCP ahead of the resistance against Japan,” kidnapped him in Xi’an. Jiang was forced to stop the civil war against the CCP so that the whole nation would be united to cope with the threat from Japan.3 With the outbreak of the War of Resistance against Japan the next year, the GMD and the CCP formally established an anti-Japanese “united front.”

During China’s eight years of the war with Japan, Jiang’s gains seemed significant. By serving as China’s paramount leader at a time of profound national crisis, he effectively consolidated the legitimacy of the rule of his party and himself in China, which, after 1942 and 1943, was further reinforced by American-British recognition of China under his leadership as one of the “Big Four.” In the meantime, however, the foundation of Jiang’s government had started to crumble. In fact, in having to focus on dealing with the Japanese invasion, Jiang failed to develop effective plans to cope with the profound social and political problems China had been facing throughout the modern age. Consequently, corruption spread further in Jiang’s government and army during the war years, which significantly damaged his reputation as China’s indisputable national leader.4

The most serious potential challenge to Jiang’s government, however, came from the CCP. China’s deepening national crisis in the 1930s, and the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, saved the CCP and the Chinese Red Army from imminent final destruction. Holding high the banner of resisting Japan during the war years, the CCP sent its military forces into areas behind the Japanese lines to fight a guerrilla war.5 Although Mao Zedong, the CCP leader, made it clear to his commanders that, rather than engaging in major battles against the Japanese, they should use most of their energy to maintain and develop their own forces,6 the simple fact that the Communists were fighting in the enemy’s rear had created an image of the CCP as a major contributor to the war against Japan.7 Throughout the war years, Mao and his fellow CCP leaders were always aware that after the war they would need to compete with the GMD for control of China.

Not surprisingly, relations between the GMD and the CCP quickly deteriorated as the war against Japan continued. Early in 1941, the Communist-led New Fourth Army, while moving its headquarters from south to north of the Yangzi (Yangtze) River, was attacked and wiped out by GMD troops in Wannan (southern Anhui province).8 The “Wannan incident” (also known as the New Fourth Army incident) immediately caused a serious crisis in the CCP-GMD wartime alliance. In response to the incident, Mao Zedong even asserted that the CCP should begin a direct confrontation with Jiang and prepare to overthrow his government.9 And Jiang ordered the use of both military and political means to restrict the CCP’s movements.10

Pressure from the United States and the Soviet Union, however, helped prevent the GMD and the CCP from resuming a civil war at this moment. After the New Fourth Army incident, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent Lauchlin Currie as his special envoy to China to meet Jiang and other Chinese leaders. Currie expressed Washington’s concerns over a renewed civil war between the GMD and the CCP, warning that it would only benefit the Japanese.11 On 25 January 1941, Georgi M. Dimitrov, the Comintern’s secretary-general, sent an urgent telegram to Mao Zedong, warning the CCP leaders that they should not abandon the party’s cooperation with the GMD lest they “fall into the trap prepared by the Japanese and the puppets.”12 Consequently, a CCP-GMD showdown was temporarily avoided.

Neither the CCP nor the GMD, though, would trust the other. In the ensuing four years, until the end of the war against Japan in 1945, both parties put preparing for a showdown between them after the war at the top of their agenda. In 1943, Jiang published a pamphlet titled China’s Destiny, in which he claimed that the Communists would have no position in postwar China.13 The CCP angrily criticized Jiang’s “plot to establish his own dictatorship by destroying the CCP and other progressive forces in China,” calling for the Chinese people to struggle resolutely against the emergence of a “fascist China.”14 Both GMD and CCP leaders realized that when the war ended, a life-or-death battle between the two parties was probably inevitable.

The CCP’s Diplomatic Initiative in Late 1944 and Early 1945

By the end of 1944 and the beginning of 1945, the balance of strength between the GMD and the CCP had swung further in the latter’s favor. The widespread corruption within Jiang’s government, the runaway inflation in the Nationalist-controlled areas,15 and the major military defeats of Nationalist troops in the face of the Japanese Ichi-go campaign16 combined to weaken significantly Jiang Jieshi’s stature as China’s wartime national leader. In comparison, the CCP had reached a level of strength and influence unprecedented since its establishment in 1921. By late 1944 and early 1945, the party claimed that it commanded a powerful military force of 900,000 regular troops and 900,000 militiamen, and that party membership had reached over one million.17 In the meantime, the party had gained valuable administrative experience through the buildup of base areas in central and northern China, and Mao Zedong, through the “Rectification Campaign,” had consolidated his control over the party’s strategy and policymaking.18

Under these circumstances, Mao and his fellow CCP leaders believed that with the continuous development of the party’s strength, it would occupy a stronger position to compete for political power in China at the end of the war against Japan. On several occasions, Mao asserted that “this time, we must take over China.”19 To this end, the party adopted a series of new strategies in late 1944. In a political maneuver designed to challenge Jiang’s claim to a mon...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- MAO’S CHINA AND THE COLD WAR

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- MAPS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND TABLE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR AND THE RISE OF THE COLD WAR IN EAST ASIA, 1945–1946

- CHAPTER 2 THE MYTH OF AMERICA’S LOST CHANCE IN CHINA

- CHAPTER 3 MAO’S CONTINUOUS REVOLUTION AND THE RISE AND DEMISE OF THE SINO-SOVIET ALLIANCE, 1949–1963

- CHAPTER 4 CHINA’S STRATEGIES TO END THE KOREAN WAR, 1950–1953

- CHAPTER 5 CHINA AND THE FIRST INDOCHINA WAR, 1950–1954

- CHAPTER 6 BEIJING AND THE POLISH AND HUNGARIAN CRISES OF 1956

- CHAPTER 7 BEIJING AND THE TAIWAN STRAIT CRISIS OF 1958

- CHAPTER 8 CHINA’S INVOLVEMENT IN THE VIETNAM WAR, 1964–1969

- CHAPTER 9 THE SINO-AMERICAN RAPPROCHEMENT, 1969–1972

- EPILOGUE

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mao's China and the Cold War by Jian Chen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Chinese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.