![]()

Part One: Economics

North Carolina was first settled by Europeans in the mid-seventeenth century, when poor Virginia tobacco farmers in search of land moved south into the Albemarle region. At that time, the presence of powerful Indians prevented settlement further west. Disease, warfare, and colonial encroachment largely emptied central North Carolina of its native inhabitants over the next hundred years. By the middle of the eighteenth century, settlers from the middle colonies poured into the now deserted region. Most of the newcomers were small and middling farming families, who aimed for economic independence and political and religious freedom on the fringes of Anglo-American settlement. But many found that achieving and protecting economic independence was more difficult than they had hoped. In the developing economy of the Piedmont a small group of ambitious men with political connections controlled access to the means of economic advancement. The clash of values between such men, who sought to create a society dominated by large plantations and enslaved laborers, and settlers seeking a haven for independent farming families lay at the heart of the Regulation.

![]()

Chapter 1: Breaking the Way

Colonizing the North Carolina Piedmont

At the end of December 1700, a young adventurer and naturalist fresh from London set off from Charleston to explore the hinterland of Carolina, an area as yet unmapped by Europeans and “inhabited by none but Savages.” Guided by a changing cast of Indians, John Lawson and several companions walked some 550 miles in two months in a broad arc following the Santee and Wateree Rivers in a northwestern direction to the confluence of the Catawba River and Sugar Creek near present-day Charlotte, then back east toward the coast through the North Carolina Piedmont. Along the way, Lawson recorded his observations of the rich land, the abundant wildlife, and the great diversity of native cultures. The young Englishman was well aware that two centuries of contact with explorers and traders had much reduced the Piedmont Indian population. He estimated that “there is not the sixth Savage living within two hundred Miles of all our Settlements, as there were fifty years ago.” Wherever Europeans and Indians had come in contact, the latter had fallen sick and died, “being a People very apt to catch any Distemper they are afflicted withal.”1

Yet Lawson met natives everywhere. Indian guides piloted his canoe, ferried his party over dangerous rivers and swollen creeks, shot game to sustain the adventurers on the trail, killed wolves and “tygers” that threatened their safety, and found the best places to set up camp. The party spent their nights in native villages and hunting cabins, where the Englishmen partook of food and shelter, picked up a few native words, and received an education in Indian etiquette which included negotiations with native women for sexual favors. They exchanged medical remedies, compared religious beliefs, checked out communal sweat lodges, and watched ceremonies and games—all with great interest and limited comprehension.

Lawson carefully noted the possibilities for European-style development in the Piedmont. The area near the Catawba Indians on the North Carolina–South Carolina border looked like “as pleasant and fertile a Valley, as any our English in America can afford.” Near the Yadkin River, where the Saponi Indians lived, he passed through “delicious Country,” promising great returns “were it inhabited by Christians, and cultivated by ingenious Hands.” To the east beyond Sapona-Indian town, the creeks were “very convenient for Water-Mills” and “many thousand Acres” could be “fenced in, without much Cost or Labour,” to raise livestock. Near the Indian town of Keyauwee on Caraway Creek, west of present-day Asheboro, he envisioned profitable mines and hills planted with vineyards. The Old Haw Fields, used by the Sissipahaw Indians living on the Haw River some twenty miles from modern Hillsborough, were “extraordinary Rich,” with “Stone enough” and “plenty of good Timber” to build fences and homesteads for the “Thousands of Families” he thought the area could sustain. “The Savages do, indeed,” Lawson concluded, “still possess the Flower of Carolina,” with, he added, referring to the fledgling European settlements on the coast, “the English enjoying only the Fag-end of that fine Country.”2

Some fifty years later, in the fall of 1752, Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg and five fellow Moravians traveled through the North Carolina Piedmont looking for a large tract of land on which to begin a religious settlement. The Moravians, a German Pietist sect of Lutheran background, had their origins in Bohemia as part of a fifteenth-century radical movement to reform the Catholic Church. Persecuted for several centuries, they found refuge in the early eighteenth century on the estate of a German count, Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, who became their leader and reformulated their religious doctrine. Eager to found new model communities that offered separation from the sinfulness of the world and from potential enemies, and attracted to the profits a frontier region might offer, Zinzendorf at midcentury contacted the Earl of Granville, owner of the entire northern half of North Carolina, and negotiated for the settlement of a group of Moravian refugees in the province. To Bishop Spangenberg, leader of several Moravian settlements in Pennsylvania, fell the task of locating 100,000 continuous acres in the so-called Granville District.3

Unable to find the large tract the Moravians desired in the eastern part of the colony, Spangenberg was told to go to the “Back of the Colony.” Traveling 150 miles inland from Edenton to Orange County, he was not impressed with the work ethic of North Carolina’s inhabitants. Once he arrived in the Piedmont, the bishop noted with relief that among the immigrants just then beginning to move into the area were “sturdy farmers and skilled men.”4 Like John Lawson, Spangenberg appreciated the lush meadows, fertile soil, good woodland, clear springs, and creeks. And like Lawson, the bishop envisioned farms, mills, and roads. But much had changed in the half century since Lawson’s visit. While Lawson had been guided by Indians in his up-country travels, Bishop Spangenberg relied on the services of pioneering European American hunters, or “white Indians,” to scout out good lands, provide game on the trail, and carry the surveyor’s heavy chains. Where the young Englishman had seen thriving Indian villages and had met with Indians almost every step of the way, Spangenberg saw only ruins and mere traces of indigenous hunters.

“The Indians in North Carolina,” he reported to the leaders of his church in Pennsylvania and Germany, “are in a bad way.” In the Piedmont, as in the eastern part of the colony, few natives remained. Old Indian fields and abandoned villages suggested that “the Indians have certainly lived here,” but, Spangenberg estimated, “it may be fifty or more years ago.” Of the Indians who had so warmly welcomed Lawson’s party, only the Catawba, a hybrid nation living near present-day Charlotte on the South Carolina border, still inhabited the region. Most now were visitors, using the area to hunt or crossing it on their way elsewhere. Relations between Europeans and Indians were no longer amicable. In Pennsylvania, where the main Moravian settlement in America was located, “no one fears an Indian,” but in North Carolina, “whites must needs fear them.” Not merely the Indians with whom North Carolina had been at war, but “all the Indians are resentful,” the bishop explained, “and take every opportunity to show it.”5

The Moravians eventually found the large tract they were looking for. It had not been easy to find 100,000 acres in one block; advance settlers and speculators had already carved up the landscape and claimed the most fertile parcels of bottomland. The Moravians named their settlement, located on a tributary of the Yadkin River in Rowan County, der Wachau, or “Wachovia.” The religious refugees of Wachovia were but a small stream in a rapidly growing flood of colonists into the newly emptied Piedmont at midcentury, most of them “sturdy farmers” and many, like the Moravians, motivated at least in part by religious considerations. Their arrival made a reality out of Lawson’s and Spangenberg’s dreams of European-style development. Settling on former Indian lands, the newcomers staked out farmsteads, chopped down trees, cleared new ground, sowed crops, and built cabins, fences, barns, mills, and roads. Such “improvements” transformed the Indian landscape, rapidly altering its look, use, and meaning as Indian country gave way to “backcountry.”

Indians preceded European colonists in North Carolina by more than 10,000 years. During the Woodland period, a term archaeologists use to designate the period between about 1,000 B.C. and the arrival of Europeans, North Carolina Indians developed pottery and horticulture. Combining agriculture with hunting game and gathering wild plants, they initiated settlement in semisedentary villages. As their societies became more complex, they began to distinguish themselves from each other culturally and linguistically within North Carolina’s three distinct natural regions: Algonkians and Tuscarora on the coastal plain, Sioux in the Piedmont, and Cherokee in the mountains.6

Beginning around A.D. 1100, during the late Woodland period, Piedmont Indians developed what archaeologists have called the “Piedmont village tradition.” The growing acceptance of corn and the introduction of beans allowed women to produce and perfect the highly nutritious combination of corn, beans, and squash. The increasing importance of agriculture helped sustain larger populations in more permanent villages built on platforms near rivers and creeks, where the Indians could take advantage of fresh water and fertile bottomlands. Some fortified their circular villages with stockades as growing cultural differentiation and in-migration from adjacent areas created tensions and hostilities. Within villages, men and women each had clearly defined roles and powers; leadership was informal and based on personal influence.

Around A.D. 1200, some Indians in the Pee Dee Valley in the southern Piedmont began to develop more hierarchical societies, either under the influence of, or as a result of the actual invasion by, aggressive newcomers who belonged to the Mississippian culture then spreading across the Southeast. These societies built large ceremonial mounds. They were ruled by hereditary elites eager to expand their political influence and to extract tribute from surrounding, often resistant, peoples. While scholars believe their direct influence on most Piedmont Indians was minimal, their indirect influence may have been quite extensive, manifesting itself in better strains of corn, new ways of shaping pottery, and new understandings of power politics. Perhaps as the result of prolonged drought in the fourteenth century which reduced agricultural output and caused population decline, archaeologists speculate, these societies, such as the Pee Dee Indians who built Town Creek on the west bank of the Little River in present-day Montgomery County, turned back toward more democratic political rule. By the end of the Woodland period, they were again living much like their neighbors in the rest of the Piedmont.7

Piedmont Indians encountered another set of intruders in the sixteenth century. More than forty years before Sir Walter Raleigh’s ill-fated attempt to establish an English colony on Roanoke Island in the 1580s, Indians living on the Catawba and Yadkin Rivers met with the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto and his soldiers in search of gold and glory in the interior Southeast. In the 1560s, these same Indians were visited by the Spaniard Juan Pardo and his expedition. Archaeological evidence suggests that the strangers had little demographic impact in the Piedmont, somehow sparing the Indians from the devastating population losses which foreign diseases caused elsewhere in the South. From then until the mid-seventeenth century, Piedmont Indians had little contact with Europeans or Africans. While Piedmont Indians obtained some European trade goods from native intermediaries more advantageously located, European traders did not enter the Piedmont in large numbers until the 1670s, when the defeat of powerful Indians in Bacon’s Rebellion opened up the southern backcountry to Virginia traders interested in deerskins and Indian slaves. By about 1700, the Virginians were joined by traders from South Carolina, established in 1670.8

The increased contact with traders devastated Piedmont Indians by bringing more frequent warfare and exposure to disease. Even though Indians had experienced intertribal conflict before the arrival of Europeans and had traded both skins and captives with each other, competition for European trade encouraged belligerence. Groups with access to European guns gained power over those who lacked them. Successive waves of powerful southern and northern Indians such as the Westos, Savannahs, and Iroquois raided the Piedmont, eager for slaves and skins to sell to Europeans and anxious to swell their dwindling numbers with captives. Greater social contact with Europeans and with other natives spread European diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza, to which Indians had little or no immunity.

In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, European settlement began on the North Carolina coast. The adventurer John Lawson played a prominent role in the founding of Bath on the Pamlico River, where he had settled after his adventures in the Piedmont; yet the growing presence of Europeans caused friction with local Indians. When the Tuscarora attacked Pamlico settlers in 1711, Lawson was their first casualty. The subsequent Tuscarora War decimated the Tuscarora, who lost 1,400 people in battle and saw almost another 1,000 enslaved. In the thirty years between 1685 and 1715, North Carolina’s Indian population east of the mountains fell from 10,000 to 3,000. In another thirty years, that population was halved again. Those who survived buried their dead and carried on as best they could. Some found refuge among the more remote Cherokee, Creeks, or Iroquois. Others sought protection near colonial forts and towns or on the land of powerful patrons, where as “settlement Indians” they quickly lost their independence and cultural distinctiveness. Yet others combined forces in hybrid communities, blending distinct customs and languages into new collective identities.9

By the time Bishop Spangenberg searched for a place to begin a Moravian settlement, descendants of the Indians Lawson had encountered in the North Carolina Piedmont had joined the peoples living on the confluence of the Catawba River and Sugar Creek near present-day Charlotte in a loose federation of communities that eventually became the Catawba Nation. By the mid-1750s, demographic devastation due to disease, internal divisions, competition from the Cherokee for European trade, and the growing encroachment of settlers which had begun in the 1740s reduced the Catawba population to between 1,500 and 2,000 people. In the winter of 1759, smallpox brought back by warriors who had assisted the British against the French in the Seven Years’ War (known in the colonies as the French and Indian War), which had broken out in 1756, further reduced the population to perhaps 500 people, too few to resist the tide of settlers. After the war, in 1764, the British government turned the Catawba homeland into a 143,000-acre reservation to protect the Indians from further encroachment by land-hungry colonists.10

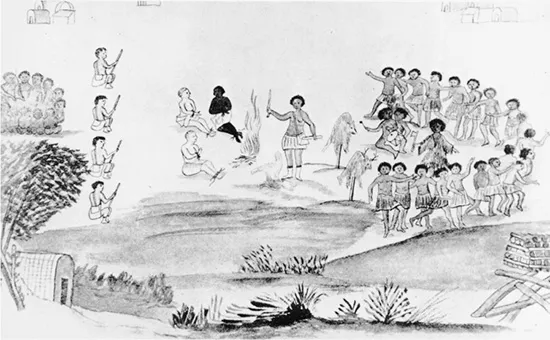

John Lawson before his execution by the Tuscarora, sketched by one of his fellow prisoners, Christoph de Graffenreid, who was later released along with his slave. Courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives.

The same process that emptied the Piedmont of Indians eventually impacted the more remote Cherokee living in the Appalachian Mountains to the west. Initially the isolated Cherokee were spared the worst of the demographic devastation and the dislocation that resulted from European colonization. However, as the number of colonial traders and diplomats increased among the Cherokee, smallpox began to take its toll. Between 1685 and 1715, the tribe’s population was reduced from 32,000 to a mere 12,000, and the deadly epidemic that hit the southeast in 1738 may have cut those numbers in half once again. In the 1740s and 1750s, dwindling numbers of Cherokee carefully juggled traditional enemies such as the Creek, colonial governments vying for their support against hostile Indians and the French, and growing numbers of traders who settled on tribal lands, but the Seven Years’ War upset this careful equilibrium.11

In the early years of the war, the Cherokee were lukewarm participants on the side of the English. Unhappy with encroachment on their land, the insulting treatment they received at the hands of their colonial allies, and the murder of some thirty of their warriors by Virginia settlers unable or unwilling to separate foe from friend, the Cherokee retaliated, after a period of increasing tension, by attacking backcountry settlements, temporarily forcing colonists in western North Carolina to flee east of the Yadkin River for safety. Between 1759 and 1761, South Carolina forces led three expeditions against the Cherokee. A small North Carolina militia contingent under Hugh Waddell, who had led North Carolina troops to Fort Duquesne in 1758 and who later commanded a force against the Regulators at Alamance, participated reluctantly. The forces destroyed Che...