![]()

Part I: Muslims

![]()

Chapter 1: Isolate, Insulate, Assimilate

Attitudes of Mosque Leaders toward America

Ihsan Bagby

American Muslims’ attitudes toward the United States and participation in American society are key factors in determining their future. In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the relationship between the American Muslim community and American society has taken on even greater importance. What path will that community take as it seeks its place in a culture that differs dramatically from Islamic cultures? Will Muslims seek isolation or involvement, accommodation or resistance? Peter Berger has argued that religion historically has served as an effective tool for legitimizing the institutions of a society by bequeathing to them a sacred purpose.1 Immigrant religious groups such as Catholics and Jews have struggled for acceptance in the American mainstream and in so doing came to adopt America’s patriotic myths, thereby stretching their sacred canopy over the United States and its political canopy over themselves. Involvement, therefore, leads to accommodation, and isolation leads to resistance and fanaticism.2

This essay explores American Muslim attitudes toward America and involvement in American society primarily by using the results from the Mosque in America: A National Study (MIA), a comprehensive survey of mosque leaders conducted in 2000.3 Analysis of the data has been supplemented by comments from interviewees at the time of the interviews, follow-up interviews conducted in 2002 with mosque leaders who participated in the MIA study, and a review of recent American Muslim literature relevant to these issues.

Emerging from the data is a picture of a religious community virtually unanimous in its desire to be involved in society—to be recognized as a respected part of the mosaic of American life. Muslim leaders clearly have opted to seek a place in mainstream America rather than to entrench themselves behind the walls of rejectionism and fanaticism. But as Muslims stand on this threshold, they harbor doubts and misgivings. Although they accept the pluralist ideal, they reject much in U.S. society. A palpable tension exists between the ideals of this self-confident body of believers and (as the Muslims see it) secular American culture. From the Muslim point of view, involvement in American society should not entail the surrender or compromise of Islamic beliefs and practices. Muslims are disquieted by what they see as the immorality of American culture and its hostility toward Islam and Muslims. In their minds, secularism, materialism, and an unfair foreign policy remain unacceptable.

So Muslim leaders are pulled in two directions. They want involvement in American society but are nervous about the possible erosion of Islamic identity and practice that might result. This concern is common among faith groups, who have long weighed the effects of a supposedly secular society on their beliefs and practices. Muslim leaders also want to have a seat at the table of mainstream America, but many are not comfortable appropriating the rhetoric and symbolism of American patriotism. The U.S. Muslim community is changing, however, and 9/11 has propelled it toward a greater commitment to involvement and accommodation. Since 9/11, the pull of those two forces has become overpowering.

This position of Muslim leaders—committed to but uneasy about involvement and accommodation—is captured by an African American Muslim in Indianapolis who remarks that the Muslim has three choices in facing America: isolate, insulate, or assimilate. The best choice, he believes, is to insulate—retain Islamic values and practices as protection against the immorality of America and anti-Islamic sentiments while remaining active in society. The metaphor of a coat as protection against wintry weather might be appropriate—the individual engages the world but is protected from harmful elements. This approach sees the importance—the necessity, even—of Muslim involvement in American society yet recognizes the dangers of identity loss such involvement portends. How else to change negative attitudes toward Islam, America’s moral standards, and its government’s policies? The middle path of insulation envisions full partnership with America, but this position implies a reluctance to embrace fully the patriotic ideals and rhetoric of America—the faithful hesitate to use Islam to pull a sacred canopy over the nation.

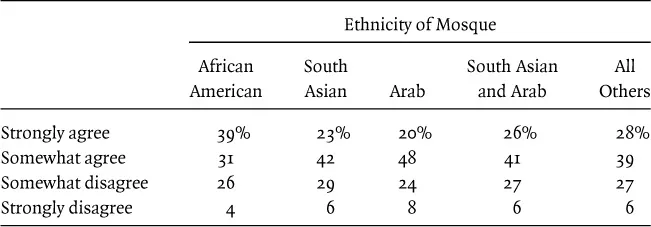

The MIA survey asked mosque leaders if they agreed or disagreed with the statement “America is an immoral, corrupt society” (see table 1.1). More than two-thirds (67 percent) of the respondents agree that America is immoral. Mosque leaders clearly are troubled by the U.S. moral climate. When talking about America’s immorality, they most often refer to the sexual mores and the prevalence of alcohol and drug consumption. Muslims feel great tension between normative Islamic culture and American society, especially in the arena of popular culture. And no wonder. Normative Islamic culture forbids premarital sex, dating, casual social interaction and touching between the sexes, homosexuality, alcohol and drug consumption, and the public show of a woman’s body. Muslims need to be insulated from America’s immorality.

TABLE 1.1: “America Is an Immoral, Corrupt Society” (Percentage Giving Each Response; “Don’t Know” Excluded from Percentages)

Strongly agree | 28% |

Somewhat agree | 39 |

Somewhat disagree | 27 |

Strongly disagree | 6 |

Muslims’ objections to this perceived immorality are not accompanied by a hatred and rejection of American society. In this regard, Muslim views resemble those of Christian evangelicals and fundamentalists who are concerned about the country’s deteriorating moral climate.

Important gradations of responses exist. Leaders who say that they “somewhat agree” that America is immoral qualify their response with various points. The most common qualification is that there are a lot of good, decent American people—in other words, not all Americans are immoral. Another qualification is expressed by a Pakistani mosque leader in New York City: “In sexual matters, America is much more immoral than the Muslim world, but when it comes to business, I think America is more moral than Pakistan.” Other comments mention that political corruption is worse in Muslim lands—in other words, not all segments of American society are immoral. Those mosque leaders who respond that they “somewhat agree” constitute the largest category—39 percent.

Those who “somewhat disagree” that American society is immoral and corrupt accentuate the positive about the United States. Most point to the highly moral people they know through their jobs, their neighborhoods, and even interfaith activities. This group seems to recognize the darker side of popular culture but to minimize its scope.

Those who “strongly agree” see immorality throughout America. One Arab mosque leader (a professional) points to America’s foreign policy (“We don’t take into account who is hurt”), high schools and teenage culture (“Look at the dress code, and then the best thing they can teach in high school is how to use a condom, and we end up with children with no parents”), and business (“When a woman has to go back to work after giving birth, that’s immoral”). A full 28 percent of all mosque leaders hold this strong criticism of American society.

TABLE 1.2: Mosques Grouped according to Dominant Ethnic Groups (Percentage of Mosques in Each Category)

South Asian | 28% |

African American | 27 |

Arab | 15 |

Mixed evenly South Asian and Arab | 16 |

All other combinations | 14 |

Note: Dominant groups have 35–39 percent of participants in one group, and all other groups less than 20 percent; 40–49 percent of one group and all others less than 30; 50–59 percent of one group and all others less than 40; or any group over 55 percent. Mixed groups have two groups with at least 30 percent of participants each.

Only 8 percent of mosque leaders “strongly disagree” that America is immoral. Explaining his response, one leader says that people cannot be outright condemned as immoral. After a thoughtful pause, possibly realizing the moral relativism implied in his remarks, the leader explains that what he means is that people cannot be dealt with effectively if they think that they are being condemned as immoral.

A number of variables will be used to analyze responses. One of the most important variables is ethnicity. Most U.S. mosques are dominated by one of three ethnic groups: African American, south Asian, or Arab (see table 1.2). The large presence of African American Muslims means that the Muslim view of America is not purely an immigrant view. The differences in opinions between the immigrant and African American leaders are distinct, and because mosque leaders are not completely isolated in ethnic enclaves, these differences have an impact and influence throughout the Muslim community.

African American mosque leaders are, in general, more critical of America’s perceived immorality than are immigrants (see table 1.3). In the MIA survey, 70 percent of African American leaders agree that America is immoral; more significantly, 39 percent “strongly agree” that America is immoral, compared to 24 percent for all immigrant mosque leaders. The more critical stance of African American leaders can be explained by the fact that most of them converted to Islam, often because they were unhappy with American culture and politics. Most African American leaders, in other words, came to Islam in part because they were repulsed by the racism they experienced and the spiritual vacuum that they saw in American society.

TABLE 1.3: “America Is Immoral” by Predominant Ethnicity (Percentage Agreeing/Disagreeing with Statement)

Note: N = 402. Not statistically significant.

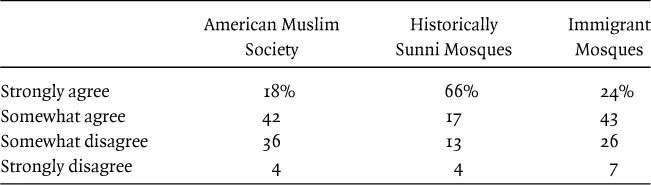

The African American Muslim community contains sharp internal differences between the American Society of Muslims (ASM), which constitutes approximately 56 percent of all African American mosques, and the historically Sunni African American mosques (HSAAM), which constitute about 44 percent of African American mosques. The ASM follows the leadership of Imam W. Deen Mohammed, who took over leadership of the Nation of Islam in 1975 and has transformed it into a mainstream Islamic organization. Imam Mohammed has come to champion patriotism, interfaith dialogue, and working within the system. The American flag has appeared on the masthead of the ASM monthly journal since 1975, and in some cities since the late 1980s, ASM mosques have organized “new world patriotism” parades on July 4.

The HSAAMS are mosques that do not belong to ASM—most never were a part of the Nation of Islam. The HSAAMS are a fractured group that have turned away from the syncretism of the Nation of Islam and sought a more authentic, normative form of Islam. I have used the phrase “historically Sunni” following Muslim leader K. Ahmad Tawfiq, who in the 1960s started using the phrase “Sunni Muslim” to distinguish between followers of the Nation of Islam and the African American Muslims who tried to follow the sunna (normative practice) of the Prophet Muhammad. HSAAMS are much more critical of the American political system, and some of them eschew interfaith dialogue (see table 1.4). They also have been more intent on digesting normative Islamic practice. Although not united in any one group, the National Umma, led for many years by Imam Jamil Al-Amin (the former H. Rap Brown), has previously had the largest group. A new organization, the Muslim Alliance in North America, has recently initiated attempts to unite hsaam mosques and other indigenous Muslims.

TABLE 1.4: “America Is Immoral,” by African American and Immigrant Mosques (Percentage Agreeing/Disagreeing with Statement)

Note: N = 401 African American mosques, 112 immigrant mosques, and 289 historically Sunni mosques. Statistically significant at .016.

Two-thirds (66 percent) of all HSAAM leaders “strongly agree” that America is immoral, while only 18 percent of ASM leaders and 24 percent of immigrant leaders strongly agree. One HSAAM leader remarks in exasperation, “You can’t turn on the radio, watch a video or TV, and not hear a whole bunch of cursing and sex. It’s ridiculous.” Overall, 83 percent of HSAAM mosque leaders, 60 percent of ASM leaders, and 67 percent of immigrant le...