![]()

1 THE DEBATE OF THE CARPENTER’S TOOLS

Shall the ax boast itself against him that heweth therewith? or shall the saw magnify itself against him that shaketh it?

—Isaiah 10:15

Annotator’s Preface

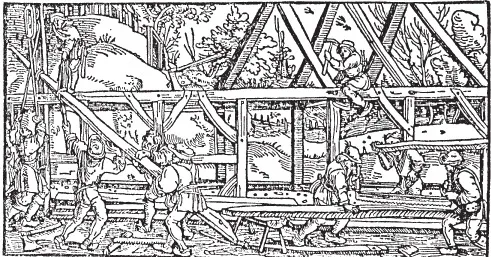

AN ENGLISH ALE HOUSE, 1500

SLIDE onto a bench here at the Sawyer’s Arms. Your brother carpenters have been drinking since before sunset, while you’ve been out hacking scarf joints in the dark. The veterans from the wars in France have already run out of stories. Give the barmaid a kiss—but check the measure of the cup that she brings. Remember at the pageant last spring? In the play The Harrowing of Hell, when all the souls in torment were liberated except one, wasn’t it the thieving alewife that Christ left behind?

Ay, now that’s better. Another pint of this and you won’t care. So what if the taste comes from the stinking Dutch habit of adding hops to the ale, calling it “biere” and pretending to like it, or from the droppings of the pigeons that roost above her brewing vat. Still, another pint of this, and that fool’s poem might seem funny tonight. He is so proud of his rhyme that I hear he has even had it written down. Now if only he knew how to read it! Ever since he heard the Mystery Play of the Nativity put on by the Wrights of Chester he thinks he can handle verse as well as he can his axe. Yea, but it’s true what Joseph of Nazareth said in the play, there’s no getting a better life through a carpenter’s work.

With this axe that I beare,

this perscer and this nawgere

and hammer, all in fere,

I have won my meate.

Castle, tower, nor riche manner

had I never in my power;

but as a symple carpenter

with those what I might gett.

Ah, here he goes. You always hear that a bad workman blames his tools—but bad tools blaming the workman? Well, sit through it one more time. You’re bound to think of something to tell your wife when you get home drunk and broke tonight. Besides, five hundred years from now—who’s to know?

Note: The verse that follows is adapted from an anonymous fifteenth-century manuscript (copy in the Bodleian Library, Ashmole 61). The original text appears in the appendix of this book.

The “trusty hatchet” is the first to deny the carpenter and his trade. The chip axe is the functional equivalent of our broad hatchet, a “one handed plane-axe, wherewith Carpenters hew their timber smooth” (1611). The word hatchet was also common at this time. In the fifteenth-century mystery play Noah and the Ark, Cam says, “I have a hatchett wonder keene to bytte well, as may be scene; a better grownde one, as I weene, is not in all this towne.” (The “sharper than thou” complex is an ancient one.) Craftsmen hewing to the lines of tradition still prefer the bare blade and “despise the saw and plane as contemptible innovations, fit only for those unskillful in the handling of the nobler instruments.”

The argument is joined by the belte, the tree-felling axe. Where the chip axe says that he can do no more than keep the wright from starving, the belte believes that hard work will be rewarded in the end. Specialized forms of the axe serve for everything from tree felling to shaping elaborate scarf joints. Five of the participants in the Debate are variants of the axe.

The twybylle, the T-shaped narrow-bladed axe “wherwith carpenters doo make their mortayses” (1584), sides with the chip axe. This contrary fellow’s two blades are set at right angles to one another. This would be the picklike, swung version of the two-faced tool, rather than the pushed and levered twivil. In an old German legend, the devil accidentally strikes himself with both ends of this tool on the backswing, making the sign of the cross on his forehead.

The wymbylle is a gimlet, the one-handed borer of little holes and the beginning of bigger things. An insightful theologian wrote in 1643 that “to use force first before people are tought the truth, is to knock a nail into a board, without wimbling a hole for it.” The rhyme with thimble is deceptive, as gimlet is seldom so big a bore: “As the wimble bores a hole for the auger.” The sound of the word and the plain imagery of the action of this tool made it popular in seventeenth-century writing. We find: “And well he could dissemble, when wenches he would wimble.”

A fourteenth-century encyclopedia described how a nephew of the legendary Daedalus “made the first compas, and wrought therwith.” Unfortunately, uncle “took greet envie to the childe, and threw hym doun of an highe toure, and brak his nekke.” Later, in 1667, Milton wrote of God taking “the golden Compasses,... to circumscribe This Universe.” Mortal carpenters wield small iron compasses. Large wooden ones usually belong to coopers, for tracing barrel heads. Although builders use compasses, as Joseph Moxon wrote in 1678, to “describe Circles, and set off Distances from their Rule,” the compass is also fundamental to the process of “scribing.” The compass is drawn along an irregular gap, transferring the contours of one surface to another. When cut to the scribed line, the two pieces fit perfectly together.

The chip ax said unto the wright:

“Meat and drink I shall thee plyght,

But clothes and shoes of leather tan,

Find them where as ere thou can;

For though thou work all that thou can,

Thou’ll never be a wealthy man,

Nor none that longs this craft unto,

For no thing that they can do.”

“Nay, nay,” said the twybylle,

“Unreason is thy only skylle.

Truly, truly it will not be,

Wealth I think we’ll never see.”

“Nay, nay,” said the compass,

“Thou art a fool in that case.

For thou speaks without advisement;

Therefore thou getyst not thy intent.

Know thou well—it shall be so,

What lightly comes, shall lightly go;

Tho’ thou earn more than any five,

Yet shall thy master never thrive.”

“Wherefore,” said the axe/belte,

“Great strokes for him I shall pelte;

My master shall do full well then,

Both to clothe and feed his men.”

“Yea, yea,” said the wymbylle,

“I am as round as a thimble;

My master’s work I will remember,

I shall creep fast into the timber,

To help my master within a stounde

To store his coffer with twenty pounds.”

The groping iron is the first “mystery tool” of the Debate. One Latin lexicon defined it as the “runcina”—“that tool of the woodworker, graceful and recurved, by which boards are hollowed so that one may be connected with another.” A seventeenth-century text states that “grooping is the making of the Rigget [furrow] at the two ends of the Barrel to hold the head in.” So a groping iron cut a groove and is a likely ancestor of the cooper’s “croze.” Medieval rooms were often finished with vertical oak wainscot (split boards) joined by V-shaped tongues and grooves. The tool that cut the groove is no longer known to us, but a “grooving iron” similar to those used until recently in Germany for joining shingles together is the likely descendant of this tool.

Our medieval encyclopedia also credited the invention of the saw to Daedalus’s nephew (before he was tossed from the tower for inventing the compass). “This Perdix was sutil and connynge of craft, and bethought hym for to have som spedful manere clevynge of timber, took a plate of iren, and fyled it, and made it toothed as a rugge bone of a fische, and thanne it was a sawe.” Saws are difficult for smiths to make. By the seventeenth century, however, Moxon’s Mechanic Exercises illustrated six varieties of saw, in contrast to the Debate’s single reference.

The Daedalus boys don’t get credit for the whetstone; the fourteenth-century encyclopedia mentions only that there are “diverse maner of whetstones, and some neden water and some neden oyl for-to whette.” The odd early custom of hanging a whetstone around the neck of a liar gets no play in the Debate. The 1418 records of the City of London state that “a false lyrer, . . . shall stonde upon the pillorye . . . with a Whetstone aboute his necke.” Thomas Tusser advised husbandmen in 1550 to “get grindstone and whetstone for toole that is dull,” advice heeded by Powhatan, who asked Captain John Smith for a grindstone in 1607.

Although I have counted the adze as one of the five axe variants in the Debate, the difference is more than just the angle of the blade. The adze is rarely used in the full-tilt chopping manner of the axe—except in the rural instance of hollowing mentioned by Tusser: “An axe and an ads, to make troffe for thy hogs.” The common carpenter’s use is best put by Moxon: “Its general use is to take thin chips off Timber or Boards, and to take off those Irregularities that the Ax by reason of its Form cannot well come at; and that a Plane (though rank set) will not make riddance enough with.” In skillful hands the adze is an exceedingly precise tool, the craftsmen holding one end of the work “with the ends of their Toes, and so hew it lightly away.”

The file, although not a proper woodworking tool, is the indispensable partner to the saw. Roman files from the first century A.D. were notched near their tang ends for use as wrests for setting saw teeth. Since files must cut other metal, they are the epitome of hardness, as in the 1484 Caxton Fables of Aesop—“She [the serpent] fond a fyle whiche she baganne to gnawe with her teethe.” Seeing her own blood and thinking it came from the file she bit harder and harder. Moxon mentions that “coarse files” and “most Rasps have formerly been made of Iron and Case-Hardened,” rather than from steel. Fil...