![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

YOUNG WOMEN’S READING IN THE GILDED AGE![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Reading Little Women

All girls are what they read; the whole world is what it reads. Ask any girl whom you have never met before what books she reads and, if she answers truthfully, you will know her, heart and soul.

On a young girl’s choice of reading depends the happiness or misery of her entire future.... If you wish to be good girls, read good books. dfsdgdfgdsfghdfg dfertgertreter ertertwertertret setertwertw4

These were not the words of a Victorian sage, but of Rose Pastor, a recent Jewish immigrant from eastern Europe. Writing as “Zelda” for the English page of the Yiddishes Tageblatt in July 1903, Pastor admonished her readers to avoid the “‘cheap, poisonous stuff ’... the crazy phantasies from the imbecile brains of Laura Jean Libbey, The Duchess, and others of their ilk!” That is, the authors of the “sensational” romances read by working-class women.1

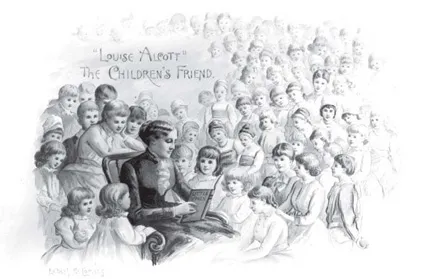

Responding to requests for advice, Pastor later elaborated on what girls should read and thus, presumably, become. Heading the list for girls sixteen and under was Louisa May Alcott, a writer known for her “excellent teachings” and one from whom “discriminating or indiscriminating” readers alike derived pleasure. With the accent on pleasure and the assurance that “good” books need not be “dry,” the columnist figured Alcott as a writer with wide, even universal, appeal. Citing a dozen titles, Pastor also commended the story of Alcott’s life by Mrs. E. D. Cheney, claiming that “the biographies of some writers are far more interesting, even, than the stories they have written.” In her judgments the immigrant journalist echoed more established critics.2

By the time Pastor wrote, Alcott’s Little Women had been prescribed reading for American girls for a full generation. Commissioned to tap into an evolving market for “girls’ stories,” her tale of growing up female was an immediate “hit,” whether judged by sales or by its impact on readers. Published in early October 1868, the first printing (2,000 copies) of Little Women; or, Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy sold out within the month. A sequel appeared the following April, with only the designation Part Second to differentiate it from the original. By the end of the year some 38,000 copies (of both parts) were in print, with an additional 32,000 in 1870. Nearly 200,000 copies had been printed in the United States by January 1888, two months before Alcott’s death.3 With this book, Alcott established her niche in the expanding market for juvenile literature. She redirected her energies as a writer away from adult fiction—some of it considered sensational and published anonymously or pseudonymously—to become not just a successful author of “juveniles,” but one of the most popular writers of the era. A very well paid one, at that.4

Even more remarkable than Little Women’s initial success has been its longevity. It topped a list of forty books compiled by the Federal Bureau of Education in 1925 that “all children should read before they are sixteen.”5 Two years later, in response to the question “What book has influenced you most?” high school students ranked it first, followed by the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress.6 And on a Bicentennial list of the eleven best American children’s books, Little Women, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn were the only nineteenth-century titles. Like most iconic works, Little Women has been transmuted into other media, into song and opera, theater, radio, and film, even a comic strip that surfaced briefly in 1988 in the revamped Ms.7 Not to mention the inevitable commercial spin-off s—dolls, notebooks, and T-shirts.8 As of May 2008, Barnes and Noble’s online database listed seventy editions, not counting foreign language–thesaurus versions, audiocassettes, CDs, paper dolls, and the like.9 No wonder Little Women has been called “the most popular girls’ story in American literature.”10

Polls and statistics do not begin to do justice to the Little Women phenomenon. Reading the book has been a rite of passage for generations of adolescent and preadolescent females of the comfortable classes. It still elicits powerful narratives of love and passion.11 In a 1982 essay on how she became a writer, Cynthia Ozick declared, “I read ‘Little Women’ a thousand times. Ten thousand. I am no longer incognito, not even to myself. I am Jo in her ‘vortex’; not Jo exactly, but some Jo-of-the-future. I am under an enchantment: Who I truly am must be deferred, waited for and waited for.”12 Ozick’s avowal encapsulates recurrent themes in readers’ accounts: the deep, almost inexplicable emotions engendered by the novel; the passionate identification with Jo March, the feisty tomboy heroine who publishes stories as a teenager; and—allowing for exaggeration—a pattern of multiple readings.

Frontispiece, Ednah Dow Cheney, Louisa May Alcott: The Children’s Friend (1888), lithograph by Lizbeth B. Comins. Courtesy of American Antiquarian Society.

Running through the testimony of nineteenth and twentieth-century readers, Ozick’s story of deferred desire and suspended identity yields an important insight into Little Women’s appeal to young females: its ability to engage them in ways that open up future possibility. As a character readers imagined becoming, Jo promoted self-discovery, revealing hidden potentialities to those in the liminal state between childhood and adulthood. If they were not yet “Jo exactly,” through Jo readers could catch glimpses of their future selves. With their own identities still uncertain, they could nevertheless emulate the unconventional heroine who strove so passionately for a future of her own making. For women growing up in the late nineteenth century, having a future outside the family was anything but assured; even well into the twentieth, it could not be taken for granted.

Little Women has been exceptional in its ability to elicit narratives of female fulfillment. As in Ozick’s case, these narratives often followed the trajectory of a “quest plot” and not—or not only—the “romance plot” women are assumed to prefer. If, as has been claimed, “books are the dreams we would most like to have,” then it is not too much to say that Little Women was the primary dream book for American girls of the comfortable classes for more than a century.13

Not everyone has the same dreams. Readers bring themselves to texts, the selves they are as well as those they wish to become. Through reading they gain entry into imaginative space that is not the space they currently occupy.14 Readers can and do appropriate texts and meanings in ways unintended by authors or publishers, or for that matter, parents and teachers. Such imaginative leaps, though constrained by historically conditioned structures of feeling and interpretive conventions, permit the reader to move beyond her everyday circumstances. As Emily Dickinson so memorably observed: “There is no Frigate like a book/To take us Lands away.”15

Young women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries developed means of transport that allowed them to chart their own directions. For those born in relative privilege, Alcott’s story often provided a focal point for elaborating dramas of personal autonomy, even rebellion, scenarios that may have helped them transcend otherwise predictably domestic futures. By contrast, some Russian Jewish immigrants, perhaps even readers of Rose Pastor, found in Little Women a model for becoming American and middle class, a way into, rather than out of, bourgeois domesticity. In this case aspiration mattered more than actual social position, so often considered the major determinant of reading practices.

Alcott’s classic was a book that enabled both sorts of readers to extend what literary theorist Hans Robert Jauss calls the “horizon of expectations.” Claiming that a “new literary work is received and judged against the background of other art forms as well as the background of everyday experience of life,” Jauss maintains that “the horizon of expectations of literature... not only preserves real experiences but also anticipates unrealized possibilities, widens the limited range of social behavior by new wishes, demands, and goals, and thereby opens avenues for future experience.”16 In other words, reading can have real-life consequences.

Are girls what they read, as Rose Pastor suggested in time-honored fashion in her 1903 column? The evidence from Little Women and from studies of reading generally suggests rather that readers interact with texts in multiple and varied ways: what readers bring to their encounters with print is critical to the construction of meaning. Readers are not simply shaped by the texts they read; they help to create them. In the case of Little Women this was literally as well as figuratively true.

“Verily there is a new era in this country in the literature for children,” proclaimed a reviewer in the “Literature” section of the December 1868 Putnam’s Magazine. “It is not very long since all the juvenile books seemed conducted on the principle of the definition of duty ‘doing what you don’t want to,’ for the books that were interesting were not considered good, and the ‘good’ ones were certainly not interesting.” The prime example of the “different order of things” was Little Women, which a twelve-year-old girl of the reviewer’s acquaintance, who read it twice in one week, pronounced “just the nicest book. I could read it right through three times, and it would be nicer and funnier every time.”17

Putnam’s reviewer was correct in sensing “a new era” in children’s literature and in assigning Little Women a central place in it. Juvenile literature was entering a new phase in the 1860s, with the appearance of several American classics of the genre, including Hans Brinker; or, The Silver Skates (1865) by Mary Mapes Dodge and The Story of a Bad Boy (1869) by Thomas Bailey Aldrich; indeed, a 1947 source claims that, together with Little Women, these titles “initiated the modern juvenile.”18 This literature was more secular and on the whole less pietistic than its antebellum precursors, the characterizations more apt; children, even “bad boys,” might be basically good, whatever mischievous stages they passed through.

An expanding middle class, eager to provide its young with cultural as well as moral training, underwrote the new juvenile market. Greater material well-being and new forms of family organization allowed children of the comfortable classes new opportunities for education and leisure, with literary activities often serving as a bridge between them. So seriously was this literature taken that even magazines that embraced high culture devoted considerable space to reviewing children’s fiction; thus the seeming anomaly of a review of Alcott’s Eight Cousins in the Nation by the young Henry James.19

Little Women was commissioned because a publisher believed that a market existed for a girls’ story, a developing genre defined by both gender and age. The book’s success suggests that his conjecture was correct. The novel evolved for the female youth market, readers in the transitional period between childhood and adulthood—variously defined as eight to eighteen or fourteen to twenty—that would soon be labeled adolescence.20 In fact, there is evidence that people of all ages and both sexes read and enjoyed Little Women, a generational crossover that was not unusual at the time: six of the ten best sellers between 1875 and 1895 could be considered books for younger readers.21

Still relatively new in the 1860s, the segmentation of juvenile fiction by gender was a sign of the emergence of more polarized gender ideals for men and women as class stratification increased.22 An exciting adventure literature for boys came first, beginning around 1850, a distinct departure from the overtly religious and didactic stories that enjoined young people of both sexes to be good and domesticated. Enjoying wide popularity in the last third of the century, when female influence was increasing at home and in school, this literature featured escape from domesticity and female authority. Often condemned as “sensational”—a contemporary critic described typical subjects as “hunting, Indian warfare, California desperado life, pirates,” the list goes on—books like The Rifle Rangers and Masterman Ready by authors like Captain Mayne Reid, Frederick Marryat, and G. A. Henty highlighted epic struggles of masculinity, including military conquest and the subjugation of natives.23

By contrast, a girls’ story was by definition a domestic story. It featured a plot in which the heroine learns to accept many of the culture’s prescriptions for appropriate womanly behavior. This formula may account for a staggering irony in the publishing history of Little Women: Alcott’s initial distaste for the project. When Thomas Niles Jr., literary editor of the respected Boston firm of Roberts Brothers, asked Alcott to write a “girls’ story,” the author tartly observed in her journal, “I plod away, though I don’t enjoy this sort of thing. Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters, but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”24 Since Alcott idolized her Concord neighbor Ralph Waldo Emerson, adored Goethe, and loved to run wild, one can understand why she might have been disinclined to write a “domestic story.” This reluctance may also help to explain how she managed to write one that transcended the genre even while defining it.

Because of its origins as a domestic story, some recent critics view Little Women primarily as a work that disciplined its young female characters, who are coerced into overcoming their personal failings and youthful aspirations as they move from adolescence to young womanhood. Alcott has even been accused of murdering her prime creation, Jo March, by allowing her to be tamed and married.25 This interpretive line acknowledges only one way of reading the story. There is no evidence that Alcott’s contemporaries read the book in this way. Like the reviewer in Putnam’s, most early critics admired Little Women’s spirit; some even found the author transgressive. Henry James, though he praised Alcott’s skill as a satirist and thought her “extremely clever,” took her to task for her “private understanding with the youngsters she depicts, at the expense of their pastors and masters.”26

Despite claims that Little Women is a disciplinary text—for its readers as well as its characters—a comparison with other girls’ stories of the period marks it as a text that opens up new avenues for readers rather than foreclosing them. The contrast with Martha Finley’s Elsie Dinsmore (1867), a story in which strict obedience is exacted from children—to the point of whipping—is instructive. In this first of many volumes, published just a year before the first volume of Little Women, the lachrymose and devoutly religious heroine is put upon by relatives and by her ...