![]()

Chapter One

Aristophanes’ Festive Comedy

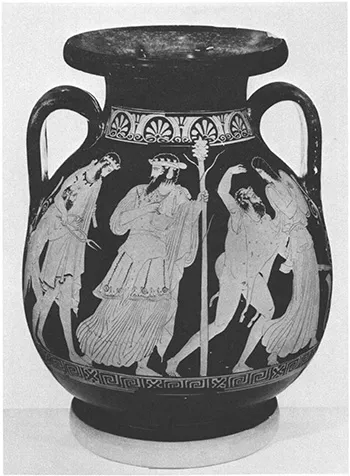

The return of Hephaistus to Olympus (with Dionysus as escort), by the Kleophon Painter, ca. 435–430 B.C., red-figure Attic pelike from Gela. Courtesy Museum Antiker Kleinkunst, Munich (no. 2361).

![]()

1 Relaxation, Recovery, and

Recognition: Peace

So the farmer-chorus sings at a crucial moment in Aristophanes’ Peace. Trygaeus, the peasant-hero, has “flown to Olympus” on his dung beetle to confront Zeus with the question, “Why does the war drag on?” But the gods have moved to regions more remote. Only Hermes, the folksy, lower-class god, remains to watch over the Olympian pots and pans. Zeus and the rest, he explains, became fed up with the Greeks after they rejected so many godsent opportunities for making peace; so now, the Greeks have been handed over to the untender mercies of War—a great hulking giant out of folktale. War has cast the lady Peace into a deep pit, and when Trygaeus arrives, he is on the verge of pounding all Greece into a salad in his huge mortar. By punning associations, all the Greek cities become salad ingredients. Not even the “dear” Attic honey will be spared. But War can’t find a pestle: the notorious Athenian and Spartan ones (Cleon and Brasidas, those hawkish generals) have just recently become unavailable; and War’s withdrawal to fashion a new pestle gives Trygaeus his chance to summon the chorus to pull out Peace. Hence their joyful entrance, singing and dancing.

What is immediately funny is the way the exuberant chorus rebel against any constraint.1 Trygaeus is forced into a spoilsport role when he insists, sensibly enough, that they pull out Peace first and celebrate afterwards. But the chorus of Greek farmers won’t stop dancing. They claim that they are stopping, but they don’t stop. The right leg has to have its fling, then the left leg. It seems that joy will not be postponed—which is, in a curious way, the recognition on which this play turns and from which it draws its resiliency, its almost manic vitality, and its hope.

Now critics whose attention is focused on what I might call “the real Athens” of March, 421 B.C., will be tempted to interpret this scene, and indeed the entire play, in one of two ways. First, they may treat it as reflecting actual hopes for peace. For almost a year, Athens and Sparta had been negotiating peace; now a settlement drew near—and a peace treaty was actually signed only a short while after the performance of Peace.2 Even if, as seems likely, Aristophanes wrote his play in the summer or early fall of 422, it seems reasonable to think that he wrote it in a spirit of hope and confidence, which would account for the unusual lightness, cheerfulness, and ease of movement that still strikes its readers today.

The other historically based interpretation of Peace would be less optimistic. In this view, Aristophanes raises strong doubts whether the peace that everyone anticipates so hopefully can be real or lasting. His exaggeration of the ease with which Peace is recovered on the stage should remind us by contrast of all those difficulties in real life that call for skepticism. In the theater, there is virtually no conflict. Everything comes easily, naturally, and spontaneously; it only takes a little communal effort to “pull out” Peace—and the rest is celebration. By contrast, an enormous amount of political effort seems required in real life, in history, to take advantage of the opportunity or kairos when it offers itself, and not to let it slip, as had happened many times before. In short: the Athenians in the audience are being told not to take peace for granted as the silly, dancing chorus do, but rather to work, and to continue to work, toward its achievement and preservation.

There is much truth in both these views. Aristophanes was heartened by the real, historical prospect of a peace treaty; Aristophanes was sensible enough not to take a lasting peace for granted. Yet both views are misleading insofar as they treat comedy as a pale reflection of historical hopes or fears. In ordinary life, celebration and joy may depend, or seem to depend, on right-thinking politics. In Aristophanic comedy, the reverse is true. Celebration and joy are an end in themselves. The first thing to do is to sing and dance with abandon; everything else will follow, in good time. Right action depends on right intention, which springs in turn from the recovery of good feeling and good will. And it is just this recovery that must not be postponed, for the Athenians, and presumably the other Greeks, have become prisoners of a vicious cycle of distrust, bad temper, and unimaginative politics. How can you break out of this cycle? Only by preempting the better temper and outlook of peacetime—which is exactly what Aristophanes’ play manages to accomplish.

Recovery is a great and central gift of comedy, but it is not easy to describe. Even as I write these words, my tense posture and anxious mind distance me, a sedentary scholar, from precisely the experience of good humor and fun which Aristophanes’ dancers celebrate and with which I am centrally concerned. It helps to relax first, to look up from my typewriter, perhaps to contemplate the five-colored jester’s cap (green, yellow, red, purple, and blue) that I wear on Mardi Gras; or perhaps, to think back to the remarkably funny farce by Tom Stoppard, On the Razzle, that I saw in Washington last week. Already it would be hard to explain why I laughed so hard, why the production (which was superb) gave such delight. The gorgeous sets and costumes, the slapstick and running about and music and wild punning and sexual innuendo and general confusion—all this was wonderful fun, and most of this would be lost in the telling. How then can I as critic recapture the gift of recovery that Aristophanes’ comedy provided if I have no living performance before me, not even before my mind’s eye, but only a Greek text—only printed words that come to us at several removes from the living play with its singing and dancing, its music and color and clowning and make-believe and interplay with the audience? How, except by analogy with my experience and yours, can the gift of recovery be explained?

Trygaeus himself is at a loss for words when Peace reappears, together with her handmaids, Opora and Theoria. The latter are personifications—Autumn Harvest and Festive Sightseeing—played by mute actors; for the emotional flavor, I translate them as Thanksgiving and Holiday.3 Here is Trygaeus’ greeting:

| Tryg. | Lady goddess! How can I greet you properly?

Where could I find a million-gallon word

to address you by? I’ve had none at home.

Greetings to you, Thanksgiving, and you too,

Holiday. What splendid—features you have,

dear goddess. And what a scent. Its sweetness

goes right to the heart, like a breath of

freedom-from-army-service mixed with myrrh. |

| Hermes | Not like a military knapsack, then? |

| Tryg. | I reject a hated man’s most hated—bag.

Your knapsack smells, you know, of onion-belching,

but she—

she brings a scent

of autumn-time, entertaining

guests, Dionysia, flutes,

tragic players, Sophoclean

lyrics, thrushes, clever little

sayings of Euripides— |

| Herm. | You’ll be sorry, casting aspersions

on the lady. She doesn’t like

a man who puts

court-arguments in plays. |

| Tryg. | —ivy, new-wine strainers, bleating

sheep, bosomy women jogging

into the fields, drunken slavegirls,

jugs of wine tilted skyward,

lots and lots of other blessings.. .. (520–38) |

Aristophanes’ list of sensual delights of peacetime is twice difficult to translate here: first, because the imaginative sensual appeal of “Sophoclean lyrics” and “thrushes” loses much of its immediacy and (so to speak) mouth-watering appeal in English translation, and over time and space; and second, because Aristophanes takes poetic delight in juxtaposing pleasurable images of sight and sound, taste and touch and smell, partly for their comic incongruity, but still more for the sake of their combined associations and their power to evoke happy occasions.4 If “thrushes” came individually and exemplified only something delicious to eat, I might translate them as “squabs,” which my mother used to serve on special occasions—just as, elsewhere, I would translate Aristophanes’ often-mentioned enkelys and lagōa and plakountes not literally as “eel” and “hare’s-meat stew” and “layered cheesecakes,” but rather more freely as filet of sole Walewska (to be eaten with a very dry Riesling), or roast beef (rare, but not too rare), or strawberry shortcake (just the way Annie used to make it when I was a boy). Please make your own nostalgic substitutions at this point. Even so, something is lost if we turn thrushes into squabs. They may belong next to Sophoclean lyrics, and not just for fun: for these good thrushes may have sung very brightly indeed before they came to provide the even greater delight of roast fowls with a good rich gravy poured over them. The accumulation of images, their sensual profusion and confusion, evokes the overwhelming beauty and richness of peace, which made Trygaeus feel the need of that “million-gallon word.” This also reflects a basic comic axiom of Aristophanes’, that all good things are related to all other good things. Food and drink, sex and rejuvenation, peace, holiday, sport, leisure, country doings, and unrestrained laughter—air rush in together like a troupe of comic revelers, once they are given the chance. Asked to help, a recent class of students suggested the smell of Thanksgiving turkey being cooked; Christmas trees; barbecued hamburgers and fireworks on the Fourth of July; and maybe a mixture of guitars, new-mown hay, Shakespeare, and honeysuckle. That is something like what Trygaeus (and Aristophanes) has in mind.

Furthermore, these accumulated pleasures are enhanced against their dark wartime background. Pleasure is always intensified by contrast: children laugh when they get out of school, and grown-ups when they leave their offices; and there is nothing like army life to make one appreciate the sheer luxuriousness of ordinary existence. That stinking knapsack is more than an uncalled-for interruption of Trygaeus’ list: it is necessary as a reminder of contrast and of the feeling of liberation. Had anyone realized how special things can be that are taken for granted normally, like those “bosomy women jogging / into the fields”? We read astrateias kai myrou as a comic zeugma, “freedom-from-army-service mixed with myrrh”; but by poetic suggestion, that release has a delightful odor. We forget it at our peril.

We do forget, and often; hence the particular quality of nostalgia with which Aristophanes invests the imagined recovery of Peace. In ordinary life nostalgia is released very powerfully by an old song heard once more, or by a remembered taste (as of Proust’s madeleine dipped in tea), or most of all, by familiar smells. I myself am strongly affected by the scent of lilacs, and of some old books (and conversely, when I visited my old school, the stench of the locker room brought back many miserable hours spent in athletics). Just so, it is the lovely scent of the goddess that brings back so much remembered happiness in a flood of sensual and mixed images. Later, too, the chorus are urged to join Trygaeus in that same strong nostalgia, that newly remembered enjoyment of things past:

Come now, people, and recall

your older way of life

that she used to provide for us:

the dried fruit and the cakes,

the figs and myrtles burgeoning,

the taste of sweet new wine,

violets growing near the well,

olive trees,

all the things we long for:

in the name of all good things,

welcome the goddess now!

Chorus Hail to you, all hail,

most gracious lady!

We welcome you,

we longed for you

overwhelmingly, and waited

back into the countryside

at long last to return.

You were our greatest good:

we know that now,

honored, most longed-for lady—

all of us who led the farmer’s life.

Earlier, when you were with us,

we could enjoy

many ordinary things,

nice and cheap and comfortable things,

back in the good old days

when you were there.

You were groats and salvation

for the farmers:

so all the little baby vines

and all the little fig trees

and all the other little

things that grow

will laugh, they’ll be so happy then

to get you back! (571–600)

It is obvious that, beyond the chorus of farmers, the Athenian audience in the theater of Dionysus is meant to feel that same remembered stab of yearning (pothos), to desire the recovery of peace with the same erotic fervor that some people idiotically save for war and empire. And here a paradox suggests itself. Peace cannot be regained until it is strongly enough desired; cannot be desired until it is remembered; cannot be remembered until it is rightly imagined—under the guidance of the comic poet employing the magic of poetry and stage. Aristophanes pre-celebrates with and for us a future that can only be built on good, hopeful feelings, and on such memories as inspire longing with hope. This is the central recovery. All other right decisions and actions must follow after it, not come before.

That is why Hermes “explains” what has been happening in wartime Greece only after Peace has been recovered and reimagined.5 The god is evidently a persona for the comic poet here. With full Olympian authority he makes the usual Aristophanic points: that the flame of war was fanned by Pericles, and later by others, out of private political and economic interests; that war escalated of its own momentum, tending increasingly to grow harsher and more violent, and to perpetuate itself through suspiciousness and hostility; and that the country folk, normally sensible but now hungry, impoverished, and confused, were cheated by the politicians, losing their chance of peace:

Then, when the working folk arrived,

packed together, from the country,

they didn’t realize how they

were bought and sold for someone’s profit,

but wanting grapes, and wanting figs,

they kept their eyes on the politicians:

and they, the speakers, well aware

that the poor were weak, and sick, and breadless,

threw out this goddess (like manure)

with two-pronged—screams, though she came back

many times over, out of fondness

for her dear Athens. Then they’d squeeze

some rich and fruitful allies, claiming,

“This man collaborates with Sparta!”

Then you’d worry the man to pieces

like a pack of starving puppies:

pale and sick and scared, our city

snapped up any slanders going.

Foreigners saw men take a beating;

they stopped the speakers’ mouths with money,

so they got rich; but all of Hellas

could go to waste, for all you noticed.

And all these things were organized

by just one man. A LEATHER-SALESMAN. (634–48)

Aristophanes never tired of displaying the gullibility...