This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The World of Ovid's Metamorphoses

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Synthesizing a wealth of detailed observations, Joseph Solodow studies the structure of Ovid's poem Metamorphoses, the role of the narrator, Ovid's treatment of myth, and the relationship between Ovid's and Virgil's presentations of Aeneas. He argues that for Ovid metamorphosis is an act of clarification, a form of artistic creation, and that the metamorphosed creatures in his poem are comparable to works of art. These figures ultimately aid us in perceiving and understanding the world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The World of Ovid's Metamorphoses by Joseph B. Solodow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Ancient & Classical Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

STRUCTURES

The Search for Structure

Since the mid-1940S Ovidian scholarship has paid great attention to the structure of the Metamorphoses. Sometimes at book length, sometimes in essays, critics have sought to identify the elements which articulate and unify the poem. Our age is perhaps characteristically interested in such questions. But there is also a special quality about the poem which provokes the interest. It is so extraordinarily varied, so ample, so free from obvious schemes of arrangement, that critics have repeatedly searched for designs which will be able to show the sense and purpose of the whole. I agree with this enterprise, though not with the particular results most have arrived at. We may begin our study of the poem by considering its structure as we work our way from large, external features in towards the heart of things.

Good clues about the arrangement of a work may be given by the beginning and the end. Stephens found that two philosophical passages, set at the extremities of the poem, suggested the significance of the whole.1 According to him, Ovid’s account of how the world was created out of the primeval chaos (1.5-88) is Stoic but also includes much that derives from Empedocles. The corresponding passage just before the end is the long speech of Pythagoras (15.75-478). Both of these are linked with Orphism, which celebrates Eros as the supreme deity. On the basis of this, and of other arguments as well, Stephens concludes that Love is the principal subject of the poem. We do not need to assess this idea here. I shall simply say in passing that, though the prominence of love in Ovid’s stories is undeniable, the series of equations involved in this view seems to me weak, and too much of the poem is omitted. What we want to notice is how structure is a tool of interpretation.

The opening and close of the poem have been used to construct a different interpretation. In a valuable essay Buchheit has pointed out matching references to Augustus as Jupiter at the beginning (in the assembly of gods held about Lycaon, 1.200-205) and the end (in connection with Caesar’s apotheosis, 15.858-60, 869-70).2 He uses this, together with other evidence, to demonstrate that in the Metamorphoses the meaning of the universe is to be viewed in relation to Rome and her history. In comparison to Stephens’s, Buchheit’s observations on the two key passages are more firmly made, but the interpretation fits the remainder of the poem less well: the vast bulk of the work has almost nothing to do with Rome.

We may take this pair of essays as a first indication of the difficulties which beset attempts to determine the poem’s structure. Both critics find in the first and last books what might be called framing elements and from them draw conclusions about the poem’s subject. But the two choose to focus on different passages. What are we to do in this situation? Decide which of the two views is superior? This is not easy, since there is something to be said in favor of each. Then accept them both? But they are at odds with one another. Better than either of these courses, it seems to me, is to recognize that still other framing structures could probably be found and, moreover, that the poem calls out for such schemes and at the same time suggests so many of them as to baffle the reader.

The structures described by Stephens and Buchheit are simple, and proposed rather than demonstrated, in that they each involve but two passages. Far more extensive and detailed are the analyses of Ludwig and Otis, which bring us closer to the problem of the poem’s entire structure. Ludwig finds the poem articulated in twelve sections, the first one belonging to prehistory (1.5-451), the next seven to mythical time (1.452-11.193), the last four to historical time (11.194-15.870).3 For Otis the poem falls into four principal sections, which he calls The Divine Comedy (1.5-2.875), The Avenging Gods (3.1-6.400), The Pathos of Love (6.401-11.795), and Rome and the Deified Ruler (12.1-15.870).4 Both, while insisting on these divisions, also recognize the continuities from one to the next. To see clearly the differences between the two let us take as a fair sample their analyses of Books Three and Four.

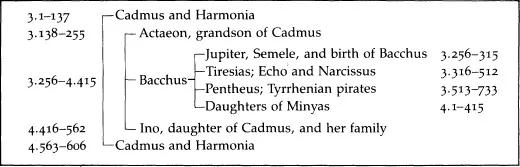

Ludwig analyzes the passage from 3.1 to 4.606 as a series of frames (see Figure 1). The outermost frame consists of Cadmus and his wife Harmonia. To one part that deals with Cadmus’ arrival in Boeotia, slaying of a dragon, and founding of Thebes (3.1-137) corresponds another that tells of the couple’s departure from Thebes and their metamorphosis into snakes (4.563-606). Inside this is set a second frame: 3.138-255 concerns Actaeon, son of Autonoe, one of Cadmus’ daughters; 4.416-562 concerns another daughter, Ino, together with her husband, Athamas, and their sons, Learchus and Melicertus. These frames surround four parts devoted to Bacchus, who emerges therefore as the central subject of the passage: (1) 3.256-315, Jupiter’s love for Semele and the birth of Bacchus; (2) 3.316-512, Tiresias and the intertwined stories of Echo and Narcissus; (3) 3.513-733, Bacchus’ opponent Pentheus, with a long inset on those other unbelievers, the Tyrrhenian pirates; (4) 4.1-415, the daughters of Minyas, who chose to spend their time in weaving rather than in worshipping Bacchus—this last part consisting chiefly of the tales told by the sisters, which are disposed, says Ludwig, in a symmetrical set of three.5

Ludwig’s full analysis includes observations regarding the section’s tone and rhythm: love in the Tiresias and the Minyades episodes contrasts with the tragic and hymnic Bacchus theme; the section rises to a climax in Bacchus’ double triumph, over the pirates and Pentheus, and his epiphany to the Minyades. He also cites details which further support the proposed structure, pointing out that Cadmus, as he leaves Thebes, is represented as thinking of the dragon, which strengthens the link between the opening and closing parts of the section; similarly, among the stories of Minyas’ daughters the first and third groups begin with a praeteritio. Several objections can be raised against this structure, among them that whereas Actaeon is a grandson of Cadmus and Harmonia, Ino and Athamas, the principal actors in their episode, are daughter and son-in-law, so the parallel between the two stories making up the inner frame is not very close; also that Bacchus is out of sight and out of mind in much of the section.

But let us be aware of the questions such an analysis raises. To what extent does the frame shape or govern or determine or even represent its contents? Can an inset by its size take precedence over the material in which it is embedded? In other words, if we find one story set within another, as happens very often in the Metamorphoses, does this arrangement imply that the outer one is more important in some way? Perhaps “border” would sometimes be an apter word than “frame.” Or, again, between successive stories, which kinds of links or other articulating features ought we to pay attention to? Identity of characters or place? Parallelism or other similarity of subject? General theme? What do we include in analysis, what exclude? (And in those cases, how do we decide what the subject or theme is?) Rhetoric of presentation—for example, beginning two sections with the same figure of speech? Comparable size in balancing units? These are quite different matters and may conflict with one another.

FIGURE 1. Ludwig’s analysis of Metamorphoses 3.1-4.606

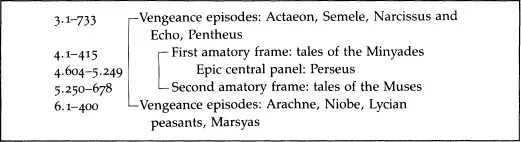

FIGURE 2. Otis’s analysis of Metamorphoses 3.1-6.400

These questions are sharpened if we compare Otis’s analysis of the same passage. His is more consistent in that it relies almost exclusively on theme. In tracing out the variations in the theme it is also more intricate and subtle, hence more difficult to summarize accurately. It too is grounded in symmetry (see Figure 2). What Otis perceives to be the fundamental unit of structure is much larger, stretching from Book Three through the middle of Book Six. Ludwig’s third section of the poem, comprising the stories from the foundation of Thebes through Cadmus’ and Harmonia’s metamorphosis (3.1-4.603), is here seen as matching another one, comprising the tales of Minerva and the Muses, Arachne, Niobe, the Lycian peasants, and Marsyas (5.250-6.400); these two sections surround Ovid’s account of Perseus (4.604-5.249). According to Otis, Perseus constitutes the epic central panel (both the preceding and the following large divisions of the poem also have epic central panels). Flanking this are two frames in which the subject is love: the tales of the Minyades, and those which the Muses recount to Minerva. Flanking these in turn are stories of divine vengeance. Jupiter, not Bacchus, dominates this quarter of the poem, and its overall theme is vengeance.6 Structure provides meaning.

Again the analysis contains elements that are persuasive. Otis points out parallels between the Song of the Minyades and the Song of the Muses, and between Actaeon and Pentheus, who open and close the first group of vengeance stories; he also notes the heightening of Juno’s vengeance from Tiresias to Pentheus to Ino. Yet, again, his analysis has lapses and omissions: for instance, the second erotic frame directly follows the central panel, whereas between that panel and the first frame intervenes an unexplained section on Ino and the metamorphoses of Cadmus and Harmonia (416-603); moreover, the tales of the Muses which center on the rape of Proserpina are not all erotic.

The point here, however, is not to praise or criticize in detail these or other particular schemes that have been proposed for the poem, but rather to allow them to draw our attention to several important features. The number and earnestness of the analyses attest the size and the incredible variety of the poem, which tend to baffle interpretation. The remarkable lack of agreement among the analyses points to the poem’s extraordinary productiveness of structures. It abounds in parallels and contrasts, symmetries and variations, with links of every sort, thematic as well as formal. If critics fail to agree (and on this poem critical agreement is minimal), it is not solely because criticism is a subjective enterprise, each critic holding his own view and there being no way of deciding among them, but rather because the poem is continually throwing out hints of structure which are neither all consistent with one another nor, if taken severally, adequate: something is always overlooked or given special emphasis. It is not that the critic was altogether mistaken; in each case he was responding to something he found in the book. None of these schemes is based on nothing; rather, hints of structure were picked up and exaggerated. The poem at the same time invites and repels attempts to interpret it through its structure.7

We can see these two sides in a pair of further observations. On the one hand, the “shapelessness” of the poem is reflected in the relation between its material and its book divisions. Occasionally the end of a book coincides with the completion of a story; ordinarily, however, the story spills over from one book to the next, and the division comes to seem arbitrary as a result. The opportunity for structure is neglected. Ovid sometimes seems to flaunt this too. Book Two ends with the disguised Jupiter carrying off Europa, but the poet saves for the start of Book Three Jupiter’s laying aside of the bull disguise and revealing himself; as if almost to deny any break, the new book begins with the word iamque (3.1, “and already”).8 Though the story of Cephalus has come to an end with the close of Book Seven, his departure is postponed to the opening verses of Book Eight—and the following story is tacked on with a casual interea (8.6, “meanwhile”). Ovid also introduces a new character or situation right before the end of a book. Phaethon appears at the end of Book One, anticipating his visit to his father. At the end of Book Eight the river god Achelous groans over his missing horn; he is questioned about it only in the following book. And though the council of Greek heroes is summoned at the very end of Book Twelve to hear the debate over Achilles’ armor, Ajax and Ulysses do not deliver their speeches until Book Thirteen. The practice of Virgil is very different: he gives to all books of the Aeneid a thematic compositional unity, marks them off clearly from one another, and structures his poem around their distinct groupings (the easiest example is the beginning in Book Seven of the second half, set in Italy now and comprised of war rather than travel).9

On the other hand, a curious instance shows us just how endemic schematizing is to critical reading of the Metamorphoses. In a distinguished essay on the poem’s humor von Albrecht discerns patterns in the presence or absence of humor and also in the different types of humor: thus he finds a long crescendo and swift decrescendo in the humor of Book One; Book Nine contrasts with Book Eight by beginning in a humorous vein; and so forth.10 So rampant is the desire to find principles of structure. My claim is not that these patterns are fictions of scholars’ imaginations, but that they lead to nothing beyond an appreciation of Ovid’s feeling for rhythm, variation, counterpoint, and the like. The soundest analysis of large sections of the poem is by Guthmüller, who in fact offers no interpretation and therefore distorts less than others.11

Organizations

METAMORPHOSIS

Structural analyses like those of Ludwig and Otis, which rely of course on abstraction, run aground on the uncapturable exuberance and variety of the poem. Several more concrete, recurring features give greater promise of indicating where the poem’s unity lies and are more likely to point us towards the book’s central concerns. Let us start with the most obvious, which gives the book its title: the diverse stories are linked by the fact that each includes a metamorphosis.12 Ovid announces his subject in the very first words of the poem: in nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora (1.1-2, “my mind is moved to sing of forms changed into new bodies”), and carries it out everywhere. In Book Three, for instance, we read of the transformation of the dragon’s teeth into the first men of Thebes, of Actaeon into a deer, of Tiresias into a woman, of the girl Echo into the natural phenomenon, of Narcissus into a flower, and of the Tyrrhenian pirates into dolphins. All told, about two hundred fifty metamorphoses are narrated or mentioned. This strikes me as not only the most obvious but also the most important unifying feature of the poem. Astonishingly, some critics have urged us to ignore this as trivial.13 This flies in the face of common sense. Moreover, a self-conscious remark carefully placed by Ovid should banish any lingering doubts. In Book Eight, the very midpoint of the whole, Pirithous, after hearing of how a girl was changed into an island, declares to the assembled company that he refuses to believe in the possibility of metamorphosis (8.612-15). Of course he is wrong, as his companion Lelex undertakes to prove with another story. To describe what metamorphosis is ought to be a crucial move in interpreting the poem.

NARRATIVE LINKS

A second regular feature is that every story is joined to the one before it through some narrative link. Ovid never just says, “Now let me tell another tale.” Some character or action or place always ties successive stories together, making of the whole an unbroken series. This is one of the meanings of the phrase with which the poet describes his enterprise at the start: perpetuum . . . carmen (1.4, “a continuous poem”).14 The series of tales beginning with Io offers a good example of this connected form of narrative. Io’s son Epaphus has a playmate Phaethon, who, challenged by Epaphus about his lineage, goes to make inquiry of his father, the Sun. Thus do we move from Io to Phaethon. Phaethon’s driving of his father’s chariot sets the world on fire and precipitates his own death. Thereupon his sisters, weeping over his death, are changed into trees, while because of the same grief his cousin Cygnus is changed into a swan. Jupiter, when making a tour of inspection through the damaged world, catches sight of the nymph Callisto, subject of the next tale. A...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THE WORLD OF OVID’S METAMORPHOSES

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE STRUCTURES

- CHAPTER TWO THE NARRATOR

- CHAPTER THREE MYTHOLOGY

- CHAPTER FOUR AENEID

- CHAPTER FIVE METAMORPHOSIS

- CHAPTER SIX ART

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX OF PASSAGES CITED

- GENERAL INDEX