![]() Part I: The Beginnings of a Boundary

Part I: The Beginnings of a Boundary![]()

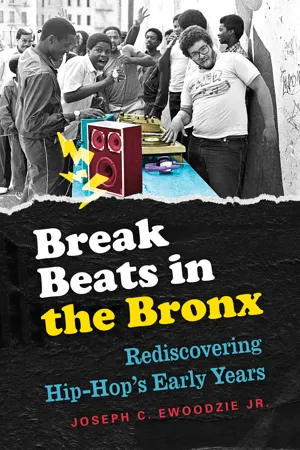

1: Herc: The New Cool in the Bronx

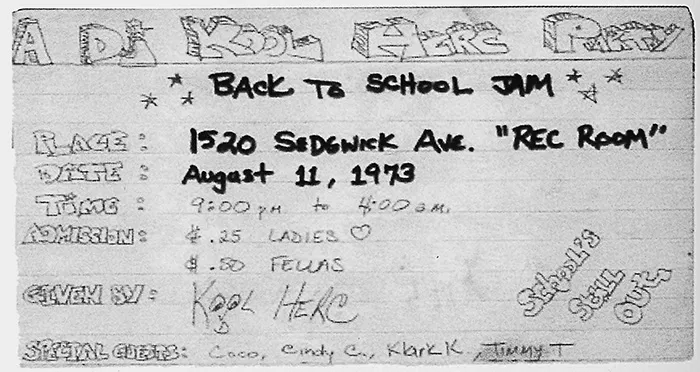

There is an age-old story that hip-hop began at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the South Bronx on August 11, 1973, at a party hosted by Cindy Campbell. As the story goes, Cindy’s main motivation was to supplement her paycheck from the Neighborhood Youth Corps so she could buy new clothes for school. She rented the recreation room in her apartment building, bought some Olde English 800 and Colt 45 beer and soda, and asked her brother, Clive (known as Kool Herc), who had been DJing house parties for three years, to perform. Cindy created handwritten fliers using index cards and spread them around her neighborhood to advertise the event. At the door, she charged twenty-five cents for the ladies and fifty cents for the guys. Word is, about one hundred people showed up.

According to several accounts, the party did not start well. As would have been done in Kingston, Jamaica, where the Campbell family was from, Clive began by playing dancehall music. But he was not in Kingston. Nor was he in Brooklyn, where Caribbean immigrants would have enthusiastically appreciated his musical taste. This was the Bronx, and people wanted something different, not dancehall or even what was on the radio. “They didn’t want to hear the smooth songs that Frankie Crocker played on WBLS and Hollywood played in the discos, records like ‘Love Is the Message,’ ” according to Dan Charnas’s version of the story. “They preferred songs with long breakdown sections . . . like ‘Get Ready’ by Rare Earth, which had a drum break that lasted two full minutes.”1 So, like any good DJ, Clive switched up his style. Instead of dancehall music, he played soul and funk records; and instead of playing songs in their entirety, he played the portion of the song with the most percussion. Just as he had hoped, this strategy turned the party out. He went from the most danceable, high-energy peak of one song to that of another so the dancers would never feel a lull. His playlist probably included the funkiest parts of songs like “Cold Sweat” by James Brown or “Scorpio” by Dennis Coffey. Herc kept the music at that high tempo the whole night, and the partygoers loved him for it. This, according to several scholars, was the beginning of hip-hop.

FIGURE 1.1 DJ Kool Herc party flier.

It is not a myth that this event occurred. A 2008 episode of the PBS Series History Detectives, hosted by sociologist Tukufu Zuberi, proved that it did. In the episode, Zuberi travels to the Bronx and interviews several people who attest to the event having taken place. He also meets Marcyliena Morgan, director of Harvard University’s Hiphop Archive, who produces a copy of Cindy’s flier (figure 1.1). Zuberi affirms that the party happened but concludes, “was it the birth of hip-hop? That’s probably too big a statement.”2

Before Herc, DJs who lived in the South Bronx and in other parts of New York City threw parties in parks and community centers. So in a sense, there was nothing special about the 1520 Sedgwick Avenue party. Why, then, does it mark the beginning of hip-hop, especially since some aspects of hip-hop existed before that event? Equally important, why does it begin with Herc, and not any other DJ? These questions motivate this chapter. Answering them forces us to take a hard look at something historians of hip-hop often take for granted. Some of the stories in this chapter, especially those about Herc, have been published elsewhere.3 I rely on them, but I supplement the empirical details with important analyses that shed new light on what we already know.

I argue that hip-hop begins with Herc, but not because of any extraordinary or unique abilities he possessed. It starts with him because he played an important role in a complex interactional process that spurred hip-hop.4 That is to say Herc’s role in this process is not just about who he is. As one writer puts it, historical explanations are not “really about individuals qua individuals or even individuals taken as a group or type, but rather about the conditions that make particular individuals particularly important.”5 In this case, it is as if the socioeconomic circumstances of the Bronx in the 1970s, combined with the social life of South Bronx youth, came together in Herc’s life to spark something new.6

The narrative about Kool Herc that I offer differs from others in a subtle but significant way: it does not position Herc as a founder or a heroic figure. Here, he is merely a teenager who happened to stand at the intersection of various social forces that pushed him into the limelight. To put it differently, Herc did not intend to invent hip-hop. When gang culture died down during the early 1970s, it left a vacuum that DJing filled. It provided a new way to gain a name, and, for various reasons explored below, Herc was the first person to use DJing to gain local clout. As a participant in other social scenes, he was able to amalgamate DJing with other activities and thereby to set in motion the making of a new social and cultural entity.

To lay the groundwork for this argument, I explore the socioeconomic background of the South Bronx prior to the 1970s. Afterward, I construct two narratives—one about graffiti-writing and another about DJing and a particular form of dancing that accompanied it—to delineate some of the vibrant activities that were part of the broader youth culture in the South Bronx even before Herc came on the scene. With both of these efforts, I characterize the place, as geographers use the term, in which hip-hop was birthed.7 Beyond noting the dire economic conditions of the Bronx during the 1970s, as previous authors have aptly done, I also point out the space and the social consequences of urban decay, and the meanings the inhabitants gave to it. More importantly, for the purpose of this book’s narrative, I highlight the range of intangible cultural practices that were present before anything called hip-hop.

Of course, the three activities, graffiti-writing, DJing, and dancing, were not the only popular activities at the time. I focus on them because they provide a useful gauge of what existed before hip-hop and also because they are essential to the genesis of hip-hop. Some may view the selection of these three activities as arbitrary, or as a form of the present-to-past approach I criticized earlier, since my selection is based on a retrospective knowledge of the way hip-hop unfolded. These are fair charges, which bring up a broader question: where should historical narrations begin when we seek to use a past-to-present approach? If we are to follow this approach explicitly, we risk falling into a trap of perpetual regression in time because, really, there is no beginning to the past.8 I construct these storylines because they provide a context for the contingent initial encounter that set in motion hip-hop’s creation. Instead of assuming that hip-hop began with these activities, I explain how, within the specific context of the South Bronx, they entwined with one another to spur something new. I illustrate how and why actors selected and combined certain existing tangible and intangible resources to create what would become hip-hop, and I pay particular attention to Herc’s role in the process. Through this discussion, I portray what historical sociologists often refer to as conjuncture: “the coming together—or temporal intersection—of separately determined sequences.”9

Urban Decay

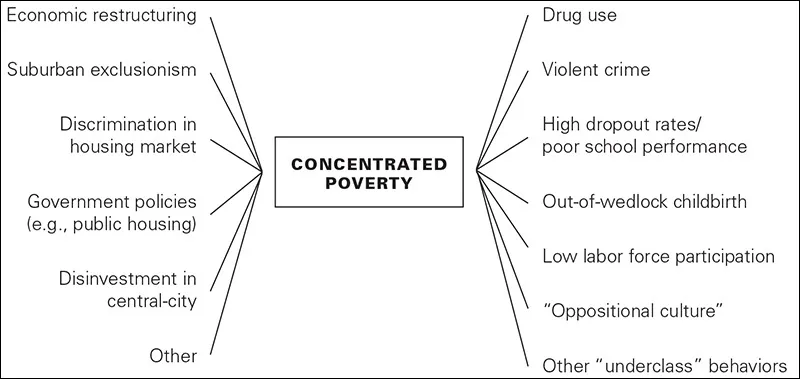

In the early 1970s, the Bronx, especially the South Bronx, became known nationally and internationally as the epitome of urban decay. When sociologists found that poverty rose by 40 percent in the top five U.S. cities during the 1970s, that the number of people living in high-poverty areas grew by 69 percent, that the concentration of poverty was most pronounced for African Americans and Puerto Ricans, and that some of the sharpest increases were in the Northeast, they were, in many ways, describing the South Bronx.10 What happened to the South Bronx, and why? Social scientists have established that various factors cause the rise and concentration of inner-city poverty, and that concentrated poverty itself leads to other social ills (see figure 1.2, below, for a summary). Using what they found, let’s explore the case of the South Bronx.

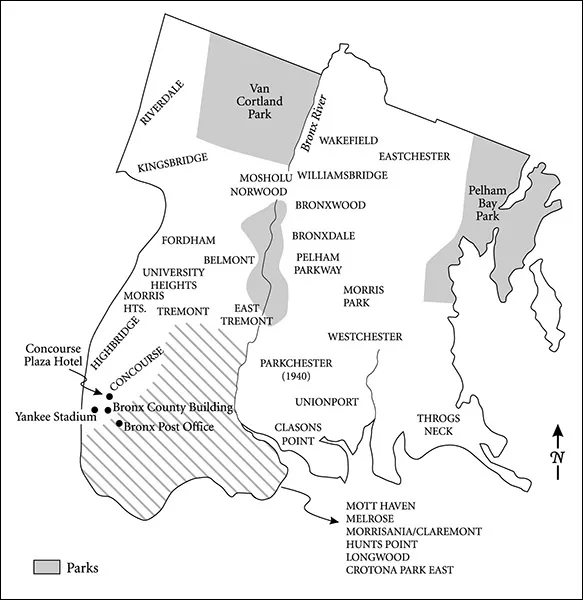

From 1890 to 1930, the population of the South Bronx grew from around 89,000 to more than 1.2 million.11 Historian Evelyn Gonzalez contends that the South Bronx attracted many new residents, especially second-generation Jews from Eastern Europe, because it was a haven for upward mobility. To begin with, according to another scholar, it offered decent housing. Many recent immigrants left the crowded tenements of East Harlem and the Lower East Side for the Bronx’s newer and more spacious apartments surrounded by parks, tree-lined boulevards, and open land.12 These apartments also boasted the latest urban architectural designs and featured modern amenities such as elevators, telephones, electric lights, and steam heat. Additionally, the Bronx offered efficient transportation. Beginning in 1900, with New York City’s construction of a new transit system, two subway routes connected the Bronx to the rest of the city. Thanks to this inexpensive rapid transit, many could afford to live in the Bronx and still have easy access to Manhattan. This made the Bronx, which consisted of diverse neighborhoods, “one of the fastest growing urban areas in the world” and earned it nicknames like “the banner home ward of the city” and “Wonder Borough.”13 By the late 1920s, it also was home to cultural institutions such as Yankee Stadium, the Bronx Zoo, New York University’s University Heights campus, and Fordham University.

FIGURE 1.2 Causes and Consequences of Concentrated Poverty, from Edward G. Goetz, Clearing the Way: Deconcentrating the Poor in Urban America (2003). (Used with permission from Urban Institute Press [Rowman & Littlefield Publishers])

The demographic makeup of the borough began to change a few decades later, however. By the 1960s, the population of the South Bronx was no longer two-thirds white; it was now two-thirds black and Puerto Rican. Several policies fostered this change. Federal Housing Authority Loans and Veterans Administration Programs, along with the suburban housing boom and ineffective urban renewal planning, provided financial incentives for whites to leave the Bronx.14 Blacks and Puerto Ricans from other parts of the city poured into the Bronx, especially the South Bronx, then the least expensive area of the borough, increasing its population from approximately 145,000 in 1950 to 267,000 in 1960. The children of these new black and Latino residents would create hip-hop. Even though they existed in different racial categories, they were bound together by the poverty they faced. Most of them had been displaced by Robert Moses, who used Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 to remove tenants from their “slums” in other parts of the city, especially in Manhattan, to make room for middle-class housing projects.15 Others, in particular southern blacks and Puerto Rican immigrants who came with fewer financial resources, opted for the Bronx. They could afford it there because the city subsidized the rent in those areas.16 Because of these measures, some of the poorest residents in New York City began to concentrate in the South Bronx.

FIGURE 1.3 Bronx Neighborhoods, 1940. (Map from Evelyn Gonzalez, The Bronx [2006]; used with permission from Columbia University Press)

Attempting to control the exodus of middle-class families from the Bronx to other boroughs and the suburbs, city officials implemented policies such as the Mitchell-Lama Law and the Rent Stabilization Law of 1969. The former provided tax incentives and subsidized mortgages to private landlords in exchange for lower rent for people earning a modest living, while the latter set limits on rent. “The Mitchell Lama housing was a disaster for the borough,” Evelyn Gonzalez explains, “[because] its co-ops siphoned off white [middle-class] families from housing that was still sound, leaving vacancies to be filled by poorer blacks and Puerto Ricans, themselves often displaced or moving away from the worsening slums, and thus spread[ing] the blight and the segregation farther.”17 The Rent Stabilizing Law failed because landlords did not profit from their rent-regulated buildings and thus did not maintain them; instead they allowed their buildings to deteriorate.18 In the South Bronx, they even burned them down.

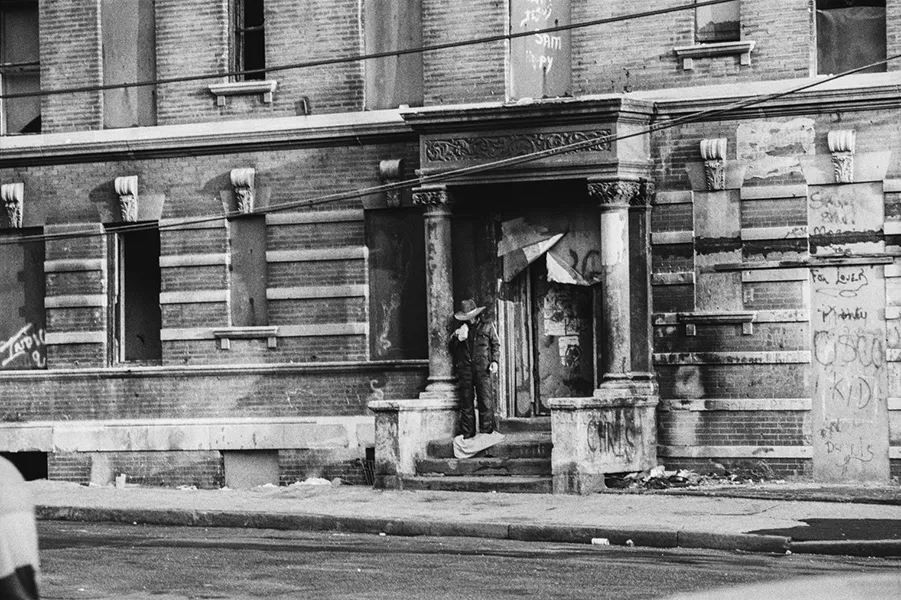

FIGURE 1.4 Urban decay in the South Bronx. (© Joe Conzo; used with permission)

Between the mid-1960s and the mid-1970s, the South Bronx lost approximately 43,000 housing units, the equivalent of four square blocks a week, to fire. From 1973 to 1977, property owners set 30,000 fires in the area. The borough became plagued by vacant lots and abandoned buildings.19 Another city policy brought about this destruction. Welfare recipients who sought better housing options would not receive reimbursements for their moving expenses unless they stayed in the same place for at least two weeks. The only exception to this rule, which was often posted in large print at welfare offices, was for tenants who had been burned out of their apartments. In such cases, tenants would immediately be moved to the top of the waiting list and would be eligible for a grant of $1,000 to $3,500. Some argue that this exception motivated rampant arson.20 Bob Werner, a police officer who served South Bronx neighborhoods during the early 1970s, believes that landlords paid for their buildings to be torched in order to collect money from insurance companies.21 Still others contend that the fires were less the work of arsonists than of social policies that promoted “benign neglect” and “planned shrinkage,” essentially pulling resources out of communities considered pathological. For instance, between 1972 and 1974, four fire companies in the Bronx were closed. Each had served 60,000 people.22

The concentration of poverty in the South Bronx can also be attributed to the loss of manufacturing jobs—a trend that was hitting the rest of New York City and many other American urban areas.23 Job loss was worse in the Bronx, however, because new tax laws introduced by the city—including new corporate incom...