![]()

Chapter One: The Common Law Vision of a Well-Regulated Society

The central parent-publick calls

Its utmost effort forth, awakes each sense,

The comely, grand, and tender. Without this,

This awful pant, shook from sublimer powers

Than those of self, this heaven-infused delight,

This moral gravitation, rushing prone

To press the publick good, our system soon,

Traverse, to several selfish centres drawn,

Will reel to ruin.

—James Thomson, quoted in James Wilson, Lectures on Law (1791)

The usual starting point for the history of police power and the American regulatory state is Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw’s decision in Commonwealth v. Alger (1851).1 There, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts upheld the power of the legislature to regulate the use of private property in Boston harbor by establishing a wharf line beyond which no private structure could be built. The regulation aimed to keep the harbor free of obstructions. Cyrus Alger was prosecuted for maintaining a pier built squarely on his own property but beyond the legislative wharf limit.2 Shaw justified this public restriction of private property rights with one of the most famous paragraphs in the jurisprudential history of police regulation:

We think it is a settled principle, growing out of the nature of well ordered civil society, that every holder of property, however absolute and unqualified may be his title, holds it under the implied liability that his use of it may be so regulated, that it shall not be injurious to the equal enjoyment of others having an equal right to the enjoyment of their property, nor injurious to the rights of the community. All property in this commonwealth … is derived directly or indirectly from the government, and held subject to those general regulations, which are necessary to the common good and general welfare. Rights of property, like all other social and conventional rights, are subject to such reasonable limitations in their enjoyment, as shall prevent them from being injurious, and to such reasonable restraints and regulations established by law, as the legislature, under the governing and controlling power vested in them by the constitution, may think necessary and expedient. This is very different from the right of eminent domain,—the right of a government to take and appropriate private property whenever the public exigency requires it, which can be done only on condition of providing a reasonable compensation therefor. The power we allude to is rather the police power; the power vested in the legislature by the constitution to make, ordain, and establish all manner of wholesome and reasonable laws, statutes, and ordinances, either with penalties or without, not repugnant to the constitution, as they shall judge to be for the good and welfare of the Commonwealth.… It is much easier to perceive and realize the existence and sources of this power than to mark its boundaries, or prescribe limits to its exercise.3

In this comprehensive passage, Shaw offered several powerful ideas that endorse his reputation as “the greatest magistrate which this country has produced.”4 He articulated a substantive notion of “the rights of the community.” He pointed out the limited, “conventional” nature of property rights—the idea that property came with an implied restriction that it should be used so as not to injure others. He defended the legislature’s open-ended police power to make “general regulations” for the “common good and general welfare.” And he made perfectly clear the sharp nineteenth-century distinction between such police regulations and state powers of eminent domain.5

The problem with Commonwealth v. Alger is that it is usually treated as a hard case—a case outside the regular ambit of early American jurisprudence. Shaw’s ideas are perceived as new and exceptional in 1851. When not ignored by legal and constitutional historians,6 Alger is discussed primarily as a novelty, a unique product of a judicial mind ahead of its time. Lemuel Shaw is seen as pioneering a conception of state regulatory power that ultimately belonged in the Progressive Era.7

Such interpretations are anachronistic. Commonwealth v. Alger was a common and easy case, firmly entrenched in the intellectual, political, and legal traditions of nineteenth-century America. Far from being the springboard for the development of police power, it was more like the capstone of a distinct era in which courts routinely upheld the state and local regulation of dangerous buildings; railways and public conveyances; corporations; the use of streets, highways, wharves, docks, and navigable waters; objectionable trades; obscene publications; disorderly houses; lotteries; liquor; cemeteries; Sunday observance; the storage of gunpowder; the sale of food; traffic in poisonous or dangerous drugs; occupations; the hours of labor; the safety of employees; the removal of dead animals and offal; and a score of other social and economic activities.8

Shaw’s arguments and language were eloquent and powerful. They were not unprecedented. In 1817 the New Hampshire Supreme Court validated a state statute prohibiting travel on Sunday with the observation that “All society is founded upon the principle, that each individual shall submit to the will of the whole. When we become members of society, then we surrender our natural right, to be governed by our own wills in every case.”9 Sustaining a New York harbor regulation, Justice Woodworth preempted Shaw by twenty-four years in Vanderbilt v. Adams (1827): “The sovereign power in a community, therefore, may and ought to prescribe the manner of exercising individual rights over property.… The powers rest on the implied right and duty of the supreme power to protect all by statutory regulations, so that, on the whole, the benefit of all is promoted.… Such a power is incident to every well regulated society.”10 Commonwealth v. Alger occupied a central place in nineteenth-century jurisprudence; but Lemuel Shaw’s great achievement lay in accurately gauging the pulse of his present, not in seeing our future.

Much of the confusion surrounding Alger and the police power in the early American polity is owed to the hold of modern liberal mythology. In law, that mythology takes two distinct forms: the public law paradigm of liberal constitutionalism and the private law thesis of legal instrumentalism.

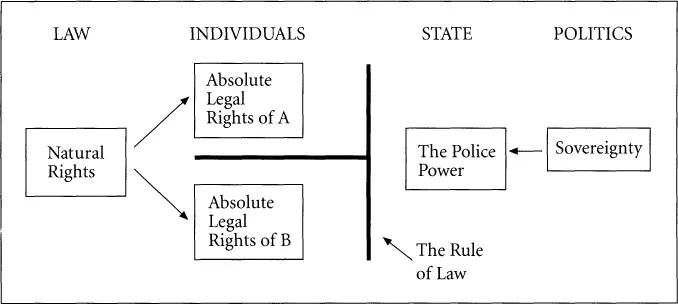

The hallmark of liberal constitutionalism is a vision of law and society emphasizing a harsh, overarching separation of the private and the public, the individual and the state. The dichotomy is total and the two are often seen as intrinsically hostile and antagonistic, as in Herbert Spencer’s The Man versus the State.11 Judges derive their distinctive political authority in the liberal constitutional order as the border guards of an all-important frontier between public powers and private rights. Duncan Kennedy illustrated the conceptual power of the liberal rule of law with a diagram (Figure 1). In the liberal schema, the rule of law is the only thing protecting us from the simultaneous threats of the private other and the public state.12

Figure 1. The liberal rule of law

American constitutional history, from this perspective, is basically a one-dimensional tale of a continuous judicial maintenance of the line between public and private, power and right, political sovereignty and fundamental law, protecting the latter from the former. Edward S. Corwin best exemplified that tradition. In a set of authoritative articles, Corwin argued that the essence of American constitutionalism was a triumvirate of sacred limiting doctrines: judicial review, vested rights, and due process.13 Those doctrines were rooted in a higher law tradition as old as Western civilization that happily realized its telos in the work of the Founders, the Federalist Papers, John Marshall, and the Supreme Court. Together those sources yielded American constitutionalism’s “basic doctrine” of shielding private property and individual rights from legislative attack via an independent, naysaying judiciary. As Robert McCloskey summarized, “The essential business of the Supreme Court is to say ‘No’ to government.”14

The new legal history of American private law originated in critique of some of the excesses of liberal constitutional history. Willard Hurst and Morton Horwitz, two of its most influential practitioners, attacked constitutional history’s obsession with a few great cases and statesmen. In contrast to Corwin’s emphasis on Founder’s talk, vested rights, and the negative function of constitutionalism, the new legal history stressed private law’s creative potential—its proactive role in the release of capitalist energy in the market revolution.15The centerpiece of this historiographical reorientation was a more realistic, sociological interpretation of law’s role in history—legal instrumentalism.16

In place of liberal constitutionalism’s vision of law as protector of an ever increasing sphere of private liberty, legal instrumentalism substituted law as dependent variable. The instrumentalist perspective emphasized private law’s reflexive qualities as a mirror and facilitator of basic social processes, most importantly capitalist development. Beginning in 1776, the story goes, American laws of property, contract, tort, and crime were revolutionized and transformed to meet the economic demands of a modernizing, industrializing society (e.g., demands for certainty, predictability, subsidy, fungibility, a reliable labor force, and the distribution of risk). Legal instrumentalism supported both conservative (a consensual freeing up of entrepreneurial initiative) and radical (a conspiracy of the bar and commercial interests) glosses.

While correcting the Whiggish tendencies of liberal constitutionalism, legal instrumentalism introduced new problems of its own. Its reductionist materialism has been ably criticized by critical legal scholars charting law’s constructive and constitutive capabilities and attacking the overdetermined notion of law as the epiphenomenal product of economic imperative.17 Indeed, the structural-functionalist sociology underlying instrumentalism has been undermined by recent developments in social and literary theory demonstrating the underdetermined nature of all human creations from language and consciousness to interests and institutions. The mechanistic separation of law from the rest of society at the heart of legal instrumentalism (law-in-the-books from law-in-action; legal concept from social fact) is no longer tenable.

The possibility of a third interpretive route beyond liberal constitutionalism and legal instrumentalism seems implicit in these critiques. Unfortunately, American legal history thus far has relied on a rough and unsatisfactory synthesis of public and private law paradigms. The two strands of legal interpretation are usually tied together in a caricature of early American legal change wherein jurists wield a conservative constitutionalism to protect property from unreasonable legislative intervention and a flexible, instrumental conception of private law to hammer away at antidevelopmental common law doctrines. A jurisprudential commitment to dynamic individual rights over the people’s welfare is seen as meeting the needs of both liberal political philosophy and a market economy. As Kent Newmyer summed up the liberal consensus: “Like judge-made private law, judge-made constitutional law responded mainly to dynamic capitalists.” The road from this understanding of the formative era of modern legalism to the Lochner Court runs straight and narrow.18

Within these two interpretive schemas, there is little room for the decision of Chief Justice Shaw in Commonwealth v. Alger. Alger was not a constitutional or a liberal opinion in the ordinary usage of those terms. Shaw’s opinion was based primarily on the principles and doctrines of the common law. His decision trumped individual property rights with a larger notion of the “rights of the community.” Alger was also not a particularly modern or forward-looking decision. Shaw grounded his entire opinion in the “views of the law of England, as it had existed long anterior to the emigration of our ancestors to America.”19 Alger can be seen as instrumentally rational or ends-oriented only by assuming Shaw to be artfully disingenuous through fifty pages of careful legal opinion (an argument one might not want to make about the Captain Vere of American legal history).20 So, Shaw and Alger become anomalies.21

In this chapter, I take the supposed anomaly seriously, keeping at bay the two interpretive paradigms into which it does not fit. The approach employs what Thomas Kuhn and other intellectual historians have called a “hermeneutic method.” Kuhn defined it simply enough as something like sensitive reading: “When reading the works of an important thinker, look first for the apparent absurdities in the text and ask yourself how a sensible person could have written them. When you find an answer, I continue, when those passages make sense, then you may find that the more central passages, ones you previously thought you understood, have changed their meaning.”22 Among the central passages of liberal constitutionalism and legal instrumentalism, Commonwealth v. Alger is an apparent absurdity. Kuhn holds out the promise that once we understand Alger, we might rethink some previously unchallenged assumptions about law, liberalism, and the early American state.

The first step in this methodology is to take seriously the language and ideas of Shaw’s opinion and others like it. Whereas legal instrumentalism marginalizes the efficacy of legal i...