![]()

Chapter 1: Introduction

They are an introverted people, consumed by internal fires which they cannot or dare not express, eternally chafing under the yoke of conquest, and never for a moment forgetting that they are a conquered people.

—Oliver LaFarge, Santo Eulalia: The Religion of a Cuchumatán Indian Town

Shortly after eight o’clock on the evening of Sunday, 27 June 1954, President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán informed the Guatemalan people that he was resigning from office and turning the government over to the head of the armed forces, Colonel Carlos Enrique Díaz. Despite continued support for the reforms his administration had fostered, Arbenz was giving up his office because, as he told his audience, “the sacrifice that I have asked for does not include the blood of Guatemalans.”1 Following Arbenz’s resignation, the decade-long Guatemalan “revolution” quickly came to an end.

The overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán is one of the most studied events in Central American history. But most of the works that have discussed his overthrow, and the history of Guatemala’s ten years of reform between 1944 and 1954, have concentrated on national and international politics. As important as these studies have been, they leave much of the revolution unexamined. Guatemala was in the 1950s, as it is today, a predominantly rural country with an economy heavily dependent on agriculture. To understand the Guatemalan revolution, we need to examine the course of reform and reaction in the countryside.

From 1944 to 1954 the Guatemalan revolution embarked on a series of economic and social reforms. While for the first six years, under the presidency of Juan José Arévalo Bermejo, these reforms only superficially affected rural areas, from 1951 to 1954 the fortunes of the revolution were directly linked to the process of change in the countryside. It was in the countryside that the revolution prompted the most vehement opposition, and it was primarily because of the administration’s activities in the countryside that relations between it and the military became strained. It was this opposition that was most important in forcing Arbenz’s resignation.

This study is an attempt to provide a history of the revolution in the countryside and to link the changes that swept through Guatemalan municipios from 1944 to 1954 with the policies and politics of the “national” revolution. The reforms passed by the two administrations of the revolution (Juan José Arévalo Bermejo, 1945–51, and Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, 1951–54) fostered a bewildering series of conflicts in rural Guatemala. These struggles took shape around a complex mix of class tensions and ethnic, geographic, and religious loyalties. These battles, in turn, forced alterations in national policies and programs as national politicians faced rural reality. To explain these conflicts and the role they played in shaping Guatemalan history, this study will proceed in four stages. First, it will provide a brief survey of rural history and a short theoretical discussion of the role peasant communities played in Guatemala’s national political and economic life. The second stage will present the major economic, social, and political currents of the revolution, with an emphasis on the sources of political instability. The third stage, which constitutes the major part of the study, will examine the activities of the national political organizations in rural Guatemala, the reaction of various elements of rural society to these activities, and the conflict that developed around them. A major focus of this section will be a discussion of the Agrarian Reform Law of 1952 and its application. Fourth, the role rural conflict played in hastening the end of the Arbenz administration will be analyzed. The study will conclude with a brief examination of the dismantling of the revolution in the countryside and an assessment of the legacy of this decade.

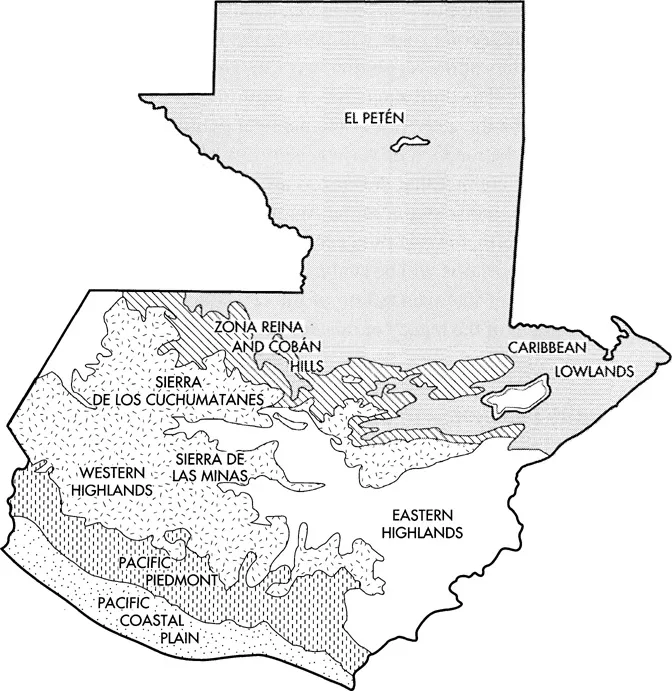

Community Formation in Guatemala

Guatemala, a relatively small country of slightly over 42,000 square miles, offers incredible diversity in climate and terrain primarily due to a backbone of mountain ridges that passes through the country from the northwest to the southeast. These mountain ridges define the various geographic and climatic regions of Guatemala: the Pacific coastal plain and piedmont, the western and eastern highlands, the Cobán plain, the Atlantic coastal plain, and the vast Petén rain forest that stretches off to the northeast. The highlands and the extension of the western highlands into the Cobán region constitute approximately one-third of the total area of the country and contain the majority of the population. The mountain ridges and volcanoes create a mysteriously beautiful landscape of isolated valleys and high plateaus. It is in these western highlands and the Cobán that the bulk of the country’s Indian population lives, most located in small towns and villages linked by paths trodden deep into the sides of the surrounding hills. The eastern highlands (often referred to as the Oriente), with poorer soils and inadequate rainfall, are less densely populated and have a higher percentage of non-Indian residents. The melancholy beauty of the western highlands is missing, but the sense of isolation is as apparent.

It is in the villages and towns of these three regions that most of the story of the revolution in the countryside takes place. Through centuries of history, these towns became strong but often conflictive communities, with a political and social structure deeply attached to local tradition. The Spanish conquest, begun in the Guatemalan highlands in the 1520s, initiated a terrible period of death and despair. The greatest toll was taken by European diseases that attacked even before the first meeting of Spaniard and Indian and, through the course of a century and a half of sporadic epidemics, killed between 75 and 90 percent of the preconquest Indian population. This loss of life tore the social fabric of native society apart and increased the burden of tribute and labor borne by those who survived.

MAP 2. GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS

However, Mayan communities in the highlands emerged from this destruction with a new culture — a conquest, peasant culture that integrated Spanish and Indian influences. The Indian community was a product of conquest, its subordinate and subjugated status constantly reinforced. The core of the new culture was the community. “Community” in colonial Guatemala was to some extent determined by the church and the crown through the reducciones (forced settlement of natives in “congregations”) carried out in the sixteenth century. These reducciones in turn established the basis for the over 300 municipios that existed during the revolution. But these communities also reflected preconquest settlement and customs. The community was organized around a religious/political hierarchy that was outwardly Catholic but essentially native. The primary focus of the community was land, and, while numerous types of landownership were recognized, most land was community controlled.

Various types of tensions were apparent in these communities. Colonial policy tended to condense social distinctions in native society, removing the higher levels of nobility from their exalted positions and freeing natives from enslavement, at least by other Indians. Nonetheless, social distinctions, often based on enduring noble status, continued to exist well into the nineteenth century. In addition, the reducciones had, in some cases, forced distinct Indian communities to merge. These prereducción entities maintained separate identities and competed for community resources.2

In the years between the formation of these communities and the revolution, a variety of influences emerged. Some fostered the disintegration of the community, some assisted social and economic differentiation within it, and some helped integrate rural communities into national politics and the economy. But other influences reinforced identification with the community, inhibited differentiation within it, and kept alive the memory of the conquest. In addition, a new element was added to rural society: Ladinos. Ladinos came in a variety of shades. The term was usually applied to those who were the product of Indian and Spanish miscegenation, but it was also used to identify Indians who no longer fit into “Indian” society. As such it was an arbitrary means for identifying those who had passed a very flexible line in the process of cultural borrowing. In the western highlands, where Indian population levels had remained higher than elsewhere in the country and where labor demands had been more moderate during much of the colonial period, Ladinos generally comprised a tiny minority of often impoverished rural petit bourgeoisie. In the eastern highlands, where Indian population levels were lower and labor demands had prompted many Indians to abandon their communities, Ladinos were often the majority; they were peasants and rural workers as well as shopkeepers and professionals.3

Even before the colonial period ended, the Bourbon monarchy had begun to attack many of the bases of these distinct peasant communities. With independence, the Liberal governments continued these policies even more forcefully in their desire for economic growth, national integration, and cultural assimilation. Communal landownership was discouraged, and the religious/political hierarchy that had developed around the church was attacked. Liberal administrations also began to tax Ladino peasants, both individually and collectively through charges against village funds. The Liberals’ desire to shape Guatemala in the image of Europe was temporarily thwarted by a successful, combined Indian/Ladino peasant revolt led by Rafael Carrera in the 1830s. Carrera dominated Guatemalan politics for most of the next three decades, and during this time peasant landholding and village political and religious structures were under less pressure than they had been previously. This policy of benevolent neglect was assisted by the political dominance of Guatemala City merchants who depended on peasant producers for their major export crop, cochineal, and thus felt little incentive to alter landholding patterns.4

This respite came to an end in the 1870s when a new generation of Liberals swept to power on the coattails of a new, infinitely more profitable, export crop: coffee. In 1871, Liberal politicians in the capital and landowners in the western highlands, anxious for incentives to expand coffee cultivation, led a successful revolt that forced Carrera’s successor from power. In the ensuing decades, a series of Liberal dictators passed laws that increasingly favored coffee planters in their struggle to attain sufficient land and labor.

Using an increasingly “professional” military with officers trained at a newly created military academy, the Escuela Politécnica, and a tightly controlled rural militia, the Liberal governments strengthened national control over rural areas. Political power in rural areas was often wielded through local caudillos with direct links to the president. But the economic dominance of Guatemala City, the importance of export agriculture, and the restricted development of internal, secondary market centers insured that few local caudillos were able to develop broad connections and thus challenge the power of the president. Consequently, Guatemala experienced a succession of strong presidents who developed stable and enduring regimes that, with the exception of a brief period of experimentation, moderate reform, and instability in the 1920s, continued until the coming of the revolution with the overthrow of General Jorge Ubico Castañeda in 1944.5

In the process of promoting the cultivation of coffee and other export crops, the Liberal regimes facilitated the development of two foreign enclaves in Guatemala. The most important of these was a group of German coffee planters who by 1913 owned 170 fincas (farms or plantations), 80 of them in the Cobán region, and marketed the bulk of Guatemalan coffee. The other significant enclave was the U.S.-owned United Fruit Company (UFCo) and its appendages: the International Railways of Central America (IRCA) and the UFCo Steamship Lines. Through its control of vast areas of land, rail and steamship transportation, and Guatemala’s major port, Puerto Barrios, the UFCo (or the octopus, “el pulpo,” as it became known in Guatemala) dominated much of the Guatemalan econom...