![]()

1 The Many Faces of Fashion in the Early Eighteenth Century

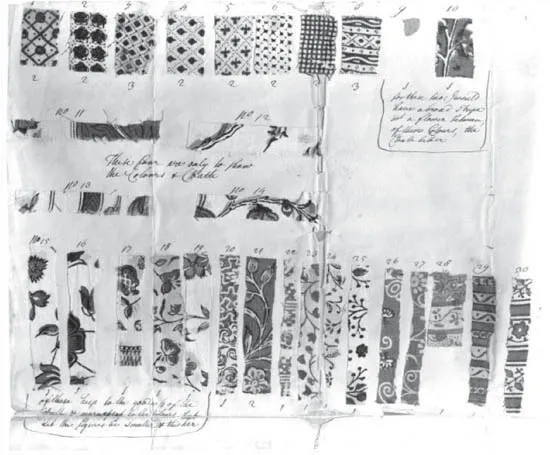

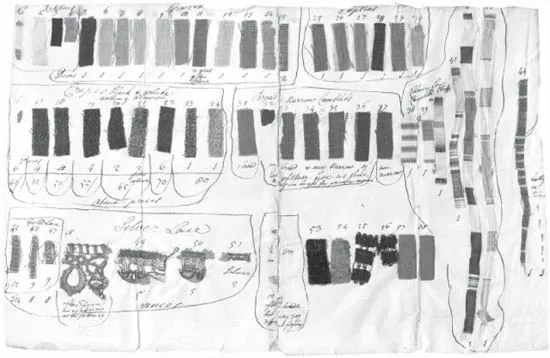

When Mary Alexander, a merchant who operated a business with her husband, James, in New York, placed a large order for fabric with her English suppliers in 1726, she included three pages of samples: a sheet filled with ribbon pieces, another displaying fifty-eight mixed fabric swatches, and a third containing thirty strips of calico and chintz. The sheets and their contents remain preserved as beautiful artifacts, bright and textured collages in which the materials have retained their brilliance after nearly three hundred years. A viewer is struck not only by the quantity of fabric Alexander ordered but the variety of colors, patterns, textures and qualities—including black and white crapes, camblets of deep fuchsia and aqua, blue and red striped calicos, and gold and silver laces. Yet whatever the sheets’ aesthetic appeal, they served a clear commercial purpose: to communicate to Alexander’s suppliers with exacting precision what she desired for her market. They were a visual guidebook of sorts, one in which she sometimes scrawled notes alongside a fabric she wanted in a tone “less blewish” or to have “a wider stripe.”1 The specificity of Alexander’s requests suggests the particular demands of her market.

Yet no matter what merchants such as Alexander ordered or received, they promoted the fabrics in the public prints as the latest and most fashionable styles from abroad—one of the many contradictions that characterized the sartorial culture of the port cities.2 Alongside newspaper advertisements that featured the language of fashion appeared other notices seeking the capture of self-emancipated servants and slaves who had taken or were wearing clothes of the same sorts of fabrics Alexander ordered, or garments “made fashionable.” Such descriptions expressed an assumption that people knew what the phrase meant and thus what such a coat or gown looked like—a style that was, on the one hand, exclusive and cosmopolitan and yet, ironically, made its wearer legible as a “lower sort.” These linguistic juxtapositions, which helped to create material distinctions, had the power to influence the very meaning of “fashion,” which possessed many and varied

Swatches of material attached to sheets, used by Mary Alexander, ca. 1750. The use of swatches and text allowed merchant Mary Alexander to show and tell her supplier in England precisely what she desired in an order for fabrics. Department of Manuscripts, Alexander Papers, negative number 26276b, Collection of The New-York Historical Society.

Patterns of eighteenth-century ribbons, grazets, poplins, crapes, broad and narrow camblets, camblet stuffs, gold and silver lace, and various unidentified textiles used by Mary Alexander, ca. 1750. Department of Manuscripts, Alexander Papers, negative number 26276g, Collection of The New-York Historical Society.

associations in the port cities, from high status to low rank, and metropolitan affiliation to colonial position. Although fashion in dress was a site for expressing hierarchies of rank, gender, and empire, individual expressions and the variety of styles adopted by an increasingly diverse population could undermine how these forms of order were supposed to “look” in the eighteenth century and compromise easy associations of dress and identity.3

Examining the range of sartorial forms that characterized urban colonial settings reveals the various practices of distinction that produced a complicated and often confusing social landscape in the port cities of British North America. Calling an item “fashionable” or “the fashion” suggested both its aristocratic, European credentials and its widespread appeal. Fashion was at once elite and popular, exclusive and accessible. The fashion, dictated by Paris and London, might signify the scope and spoils of trade with “exotic” locales, participation in a cosmopolitan world of commerce and culture, and connection to the sphere of the court and the beau monde. But, as the case of the fabric calico suggests, it could also be associated with the colonies. Even as fashion in dress gestured toward a broad geography, it possessed intensely local significance, serving as a means of distinguishing among and within social groups; achieving sartorial distinction within a social circle was as important as distinguishing among ranks.

Although arenas of display such as tea tables and balls, with their imperial associations, segregated a city’s population by rank, city streets brought people into regular contact with one another. It was in this “out of doors” setting that fashion, materially and conceptually, could also be associated with socially and geographically mobile bodies of the “lower sorts.” Critics bemoaned that people of low rank and little means dressed above their station, but historians should not necessarily follow their lead by regarding such practices as social emulation. Whether the garments were purchased or pilfered, luxe or plain, fashion in dress was about distinguishing oneself sartorially in ways that could result in social confusion; such illegibility was often intentional. Some attempted to dress their way out and up, while others chose to dress down and out. As a material practice and a concept, fashion was protean and shifting, its meanings unstable, contested, and as various as changing styles themselves. It was Atlantic but local; metropolitan and colonial; a would-be establisher of imperial and social hierarchies and their potential obscurer.

Arenas of Display in the Port Cities

The play of fashion in dress would have meant little without an audience. In order to communicate social codes and personal identity, attract attention, and engender desire, attire had to be paraded before other eyes and was often chosen with such reception in mind, even when choices were circumscribed. The visual consumption that fashion at once encouraged and relied upon fueled the engine of material consumption; this was the function of fashion and the distinctions it created. Yet the transmission of certain messages did not ensure their unaltered receipt; the appraising gaze could give and the gaze could take away. Since people often dressed to impress, all the while assessing others’ fashion choices, sociable settings were see-and-be-seen arenas of display, acquiring the quality of competition spaces. In some venues that suggested urbane cosmopolitanism, such as around tea tables in private homes or in assembly rooms, elites viewed and competed chiefly with one another. Other arenas, such as churches and the city streets themselves, brought residents of various ranks into one another’s visual fields. As the port cities matured economically and culturally, they provided many opportunities for sartorial display and arenas to showcase it, some more exclusive than others.

The Scottish émigré and keen social observer Dr. Alexander Hamilton frequented and recorded the range of venues over the course of his journey from Maryland to Boston and back in 1744. As a gentleman, Hamilton enjoyed entrée into virtually every social space, from modest roadside taverns and inns to wealthy homes and sumptuous assemblies, and everything in between. He used settings and activities as a means of comparing the northern port cities, creating a geographic hierarchy of refinement based on how—and where—residents vetted their sartorial choices and engaged in social intercourse.4

The most “private” settings were homes where people dined or took tea. By midcentury, many British Americans drank tea with breakfast among family and socially in the afternoon, and Hamilton visited tea tables in every place he visited. As spaces where groups of social peers gathered, they were semipublic arenas of fashion, especially for the women who oversaw the tea ceremony. Tea drinking evolved into an “elaborate kind of theater” with roles that had to be properly mastered and expensive props that called for correct handling. The hostess or mistress of the house both directed the production and served as its leading lady, making and pouring the tea, while expecting the supporting cast of guests to know their parts, that is, how to consume it. A complicated ritual, taking tea also involved a wealth of objects known as the “equipage”—pots, cups, saucers, spoons, and linens of varying degrees of fineness, as well as the tea table itself—all of which indicated the position of the hostess and her husband. Around the table everyone was on display, but no one more so than the woman who presided over it as director of the show and its star.5

With respect to more public or semiprivate venues, Hamilton had high expectations. Disappointed when Philadelphia failed to supply the desired forms of elite sociability, he wrote of the town’s apparent “aversion to publick gay diversions” such as balls and concerts. By contrast, he lauded Boston’s regular “assemblys of the gayer sort.” As scholar David S. Shields has shown, the members-only dancing clubs that sprung up in most British colonial cities were primary arenas of fashionable display and social competition among local elites. Dancing the minuet one couple at a time put a man and woman on display as all eyes fixed on two figures. New York, “one of the most social places on the continent,” according to William Smith, boasted balls and “concerts of musick.” Just a few years later, the Quaker City would have its own dancing society, the Philadelphia Assembly. But in 1744, lacking such settings, Philadelphians relied on church as a backdrop, Hamilton observed, although he noted this practice of church as tableau in each of the cities. Again, he reserved the highest praise for Boston. There he found the women “in high dress” at meeting and the men “more decent and polite” in their clothing than those in other towns. While balls were accessible only to elites, and therefore provided places to perform social distinction within a circumscribed in-group, church supplied a more socially heterogeneous setting where elites might not only view one another but see others and be seen by them.6

Whether in drinking, dancing, or worshiping, the relationship between high rank and high fashion was well established within these fairly insular communities, networks in which everyone likely knew everyone else. Yet their insularity by no means made them safe social spaces. As Hamilton’s gossipy observations suggest, a person’s fashion choices could be discussed and critiqued. While tea tables were notorious for this sort of chat, which critics denounced as insipid and yet powerfully cutting, maligning the tea table’s reputation also served to displace the common practice of sartorial backbiting (often engaged in by Hamilton himself) onto those female-controlled arenas. When getting dressed for any social gathering, particularly those in which your person might be studied at some length, men and women had to consider whether to blend in and avoid censure but also forgo admiration or to step out sartorially and potentially invite both.

Similar calculations influenced appearances made “out of doors,” on the city streets. In assessing this most public and heterogeneous arena of display, Hamilton initially considered New York City supreme, approving of its “urban appearance” and its lively “promenade” in which the ladies appeared dressed far better than in Philadelphia, he observed. But New York was ultimately bested again by Boston, where people ventured “rather more abroad than att York.” The existence of settings similar to the walks and pleasure gardens of London, and residents willing to take full advantage of them, was a key benchmark of refinement for Hamilton, for whom the promenades almost functioned as movable, outdoor assemblies.7 But North American cities were not populated by the wealthy alone, and although the ports were still small, “walking” cities in which many of the residents knew one another, they hosted expanding and increasingly diverse populations. People from all walks of life, hailing from places spanning the Atlantic world, jockeyed against one another out of doors, filling the cities’ streets, retail establishments, and public markets. These were places where goods could be procured in a number of ways, but they were also settings in which sartorial distinction might be viewed across social groups, taking advantage of a broader audience—indeed, multiple audiences. It was this largest and most diverse of arenas that presented the greatest challenges to securing the relationship between sartorial display and social order.

Dilemmas of Distinction

The port cities of British North America experienced rapid social, economic, and demographic changes in the third and fourth decades of the eighteenth century, a period of peace between the imperial conflicts known as Queen Anne’s (1702–13) and King George’s (1739–48) Wars. Waves of free and indentured Europeans, and a smaller but still significant number of free and enslaved persons of color, mainly Afro-Caribbeans, enlarged and diversified the populations of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Charleston’s population, at 50 percent African American, reflected its position as the capital of a colony whose social and economic order rested on chattel slavery, but the city also put the wealth and refinement of its planter ruling class on obvious display. By the 1720s all towns housed weekly newspapers that disseminated information about trade, goods, the courts, and imperial and provincial politics, fostering a colonial culture of print. The cities enjoyed new degrees of prosperity due in part to the spoils of burgeoning trade, yet even as their total wealth increased, economic stratification was shaping their social landscapes.8

As the ports grew in size, demographic diversity, and cultural sophistication, residents developed tastes for imported goods, items that could improve a person’s style of life materially and socially.9 Even before the “flood” of consumer goods and the lengthy lists thereof that would come to typify newspaper advertisements of the 1750s,10 fashion in dress promoted social distinction yet also contributed to social fluidity in urban environments; it could establish order in accordance with early modern ideas of rank as fixed and permanent, but possessed at least the potential to facilitate social as well as geographic mobility. As such, it expressed the tension between group identity and forms of individual expression. Styles of dress signified belonging to a particular social group, whether indentured servants, Quakers, or wealthy planters, but could also set a person apart from his or her peers. At all ranks, individual choices and the practices of personal distinction had the power to disrupt a social hierarchy grounded in, and comprehended through, sartorial order.

Beginning in the early 1730s, stay makers, the artisans who created boned women’s undergarments designed to shape and hold the body, were the first advertisers in Philadelphia to place advertisements that used the term “fashion.” They attempted to attract female clients who desired stays constructed in the “latest” or “newest” fashion, items that promised to “make crooked bodies appear straight.”11 The advertisements suggest desire for the European ideal of an erect stance, sought by men and women alike in the early eighteenth century.12 Genteel carriage was no longer the exclusive province of the elite, no longer purely a consequence of lineage or great wealth. Anyone who could employ a stay maker might look “straight,” and advertisements suggest appeals to a wider reading public. Their use of the term “fashion” referred to workmanship—the process of construction, or its end result in an article’s particular make or shape—but also suggest changing styles. Erect carriage might be purchased through stays, but what underpinned and produced that posture evolved. The ads denote the importance of acquiring the latest and best stays in a period where free women of all ranks wore them or jumps, slightly more flexible garments that gave physical support to women engaged in household tasks. These women likely could not afford to adopt changing styles of stays. Although some colonists desired an erect stance, which characterized the posture of those members of society “in fashion,” the stays that helped produce it, hidden as they were from public view, were not immediately recognizable as obvious items of fashion. Still, the right stays literally underlay an overall fashionable appearance, as women of means pressed their bodies into upright submission.

Unlike stays, fabric was an obvious indicator of fashionability for men and women alike,13 and merchants and retailers promoted it accordingly. Since purveyors of goods were not as specialized in their trades as they would come to be later in the century, they sometimes sold nails and needles alongside silks and satins.14 But whereas the utilitarian items usually came last in advertisements, sometimes followed by “and other goods too numerous to mention,” fabrics appeared first and apparently listed in toto. Although many of the other durables were also fashionable or luxury items such as playing cards, looking glasses, writing paper, and spices, advertisements established a hierarchy of desirability in which fabrics always held the ...