![]()

Chapter 1: Locating Islam in Cyberspace

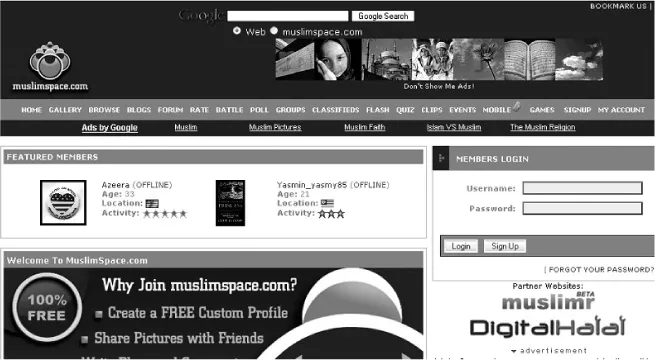

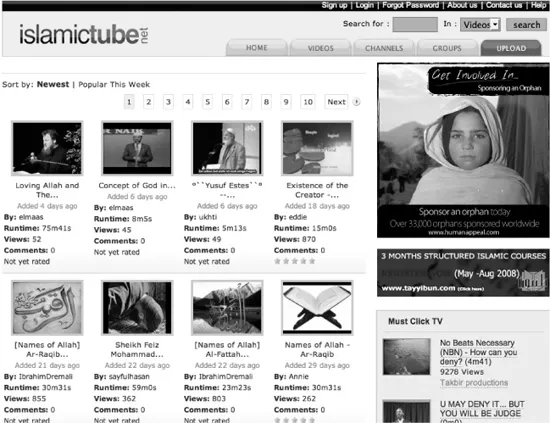

There is a sense of specific Islamic identity associated with aspects of cyberspace. These may be intentionally designed Muslim-only zones or generic areas of the Web with an Islamic footprint. One might compare the difference between Muslim content on the social networking site MySpace and the general content on the Islamic equivalent MuslimSpace. Islamic-Tube and IslamicTorrents offer video sharing and distribution modeled on non-Islamic equivalents.1 Does this sense of separateness influence how people who are not Muslim approach CIES? As with other zones of special interest on the Web, some areas of CIES are clearly more open than others. It may, however, be a cliché to suggest that, for some aspects of Islam, openness online may lead to greater understanding and empathy from outsiders. Some sites have endeavored to do this by placing explanations of religious practices on their websites. In reality, explanations of ritual practice may be less valuable to outsiders than seeing the banality and normality of other areas of online Muslim discourse, such as within social-networking sites.

On a number of levels, such developments have facilitated a rewiring of the House of Islam, allowing the Internet a central role in structures of Muslim networks and Islamic expression. Rewiring a structure is not without its disruptive aspects, but it can allow for greater efficiency through the nodes of a network. The “wiring” itself may take many technologies and forms on individual, group, and organizational levels. Some of it is collaborative and undertaken through peer-to-peer networks. Effectively, the connection may also be wireless, allowing for greater mobility and a choice of interfaces.

Through this transformational process, individuals may develop new details of religious knowledge, facilitating a form of Islamic literacy requiring familiarity with a broad range of databases and information sources. These are innovative times, not just for scholars but also for travelers on the path for religious knowledge in its many forms. One might question whether it represents new forms of religious experience that are more solitary and complex than entry into a religious school or madrassa, which may be off-limits to many surfers.

Index, MuslimSpace.com, December 2006

Online, new virtual groupings and affinities develop beyond traditional boundaries, drawing upon multiple identities. These challenge and mutate previously conventional understandings of Muslim identity, transposing familiar elements within a digital interface. CIES provide opportunities for those from nonconventional Muslim backgrounds to promote their own worldviews. These challenges to the status quo have drawn attention from traditional institutions, some of which have sought to proscribe such sites with varying degrees of success. The same mechanics of online debate and identity creation have been targeted as potentially subversive by governmental organizations unable to censor or regulate Internet pronouncements and activities that conflict with their policies.

The ways in which the Internet has been applied in Muslim contexts often reflects the ways that the medium is applied in general. Gossip, rumor, innuendo, and conspiracy theories have their place in CIES, too. Inevitably, conspiracy theories have emerged in chat rooms and elsewhere. For example, in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami disaster and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, one Internet user exclaimed, “God struck the beaches of debauchery, nudism, and prostitution.” Another wrote that “God warns humanity against perpetuating injustice,” while a third applauded “the harbinger of the Islamic caliphate.”2

Index, IslamicTube.com, May 2008

The Web is also a space where Muslim groups and individuals convene at a time of crisis. The 7/7 bombings in London saw Muslim organizations in the United Kingdom (UK) quickly issue online statements condemning the attacks.3 The immediacy of such responses was significant because other media players, such as the mainstream newspapers and broadcasters, placed hyperlinks to them in their reportage. This suggests that some site content is aimed at diffuse audiences, Muslim and other, and that it is accepted practice for references to certain Muslim sites be placed within mainstream media.

Surfers may only visit those sites that reflect their own religious-cultural-political sense(s) of identity; they may keep their visits secret from friends and family out of concern that such visits would challenge conventional ideas about identity and religious values. The anonymity allowed by the Internet can allow for lurking on sites without exposure of a real identity. Avatars allow for exploration of new ideas of religious expression and affinity, which may or may not have a relationship with the surfer’s nondigital world.

This introduces issues of physical locations, both of the surfer and the site creators, and what can be described as Islamic Web literacy. Multimedia presents religious encounters in different forms, some relating to interactivity, such as engaging with a scholar from a different context, culture, or language group. The Web offers new influences and experiences, although critics might suggest that not all of these are beneficial to their readers, consumers, and communities. These influences can include exposure to alternate religious sources of authority. These might be websites containing textual interpretative materials, video clips about religious experiences, online fatwas giving innovative approaches to rites of passage, and statements giving justification for alternate allegiances toward religious authority. One portal may provide sufficient motivation with a complete package of religious activities, guidance, exhortation, sermons, resources, and dialogue.

I am aware of Muslims who will now explain their worldview in terms of identifying with a specific Islamic website, rather than a particular local mosque or religious network. This in itself represents a radical shift of emphasis, while not negating traditional concepts of sacred space and religious authority. In some cases, such approaches suggest an augmentation and fusion of traditional and contemporary outlooks.

In other cases, a website removes the prospect of a compartmentalization of religion, with the potential for some surfers to choose to be always linked to their mosque or worldview by keeping their browser fixed to a particular site. Linking up to e-mail lists and RSS feeds (various formats of feeds derived from the Web that may be located in blogs, podcasts, and regularly updated Web content such as news sites) means that Islam can be “always on,” not just in terms of everyday words and actions but through being advised of new alerts to content and networking. Personal Digital Assistants (PDAS), BlackBerrys, and cell phones extend the opportunities to receive alerts of updates and religious information. There is potential for this to become overintrusive. While, for believers, Islam itself should be “always on” and integrated to daily life, Islamic sources also suggest that some compartmentalization of ritual practice is necessary to achieve functionality in society—Islam being, according to the Qur’an, an “easy religion.”

The Islamic biographical sources of the Prophet Muhammad note how, during the Night Journey, the Prophet and Moses negotiated the number of daily prayers from fifty per day to a more practical five so that people would be able to fit their normal lives around religious activities. The extent to which iMuslims are always online and tuned into religious content has to be determined. One critical question is: to what extent has using the Internet for Islamic purposes become a religious obligation for some? This book demonstrates that there are many people for whom being online in the name of Allah represents an obligation. How this might be interpreted and monitored is open to question.

Islamic religious authorities have found ways in which the Internet can be applied as a form of regulation within communities. In one extreme example, Saudi Arabian religious police in Medina applied the Internet to allow surfers to anonymously report perceived religious transgressions within their community via a website.4 There can be a complex relationship between paradigmatic religious practices and technical innovation in which one can often balance out the other. Issues of physical locations, both of the end user and the site creators, become significant. There are fluid ways in which they can find themselves located on a server, divorced from the restrictions of their physical space and potentially away from censorship and monitoring.

Every surfer–content provider relationship is likely to be different. Content has the potential to be an introduction to specific issues of religious authority, and/or it may act as a reinforcement tool for existing patterns and understandings. Innovation is not necessarily encouraged in some Islamic contexts. It is this very resistance to change that has also encouraged other religious authorities to come online to counter influences deemed negative in nature. In some ways, these challenge the wiki-focused collaborative approaches of Net-literate groupings seeking to articulate “new” interpretative approaches to Islam that challenge traditional hierarchies. Surfers may develop new understandings and consequent affiliations through a Web literacy combined with the breadth of Islamic databases and information sources available.

The language in which this is expressed is open to hybridization, reflecting street jargon alongside religious expression. This is true particularly in chat rooms, where participants are in conversational mode utilizing Internet conventions and cell phone slang. The smiley may be wearing hijab. In an analysis of the impact of the Internet on language and vice versa, David Crystal notes that “the prophets of doom emerge every time a new technology influences language, of course—they gathered when printing was introduced in the 15th century.” But linguists should be “exulting,” he says, in the ability the Internet gives us to “explore the power of the written language in a creative way.”5

On a related theme, Gilles Kepel, who has integrated reference to online discourse in his analyses of jihadi movements, observes: “On websites in every European language, whether jihadist or pietist, ‘trendy’ jargon blends in with an intense polemic founded on obscure religious reference to medieval scholars whose work was written in abstruse Arabic.”6 Many examples of slang, polemic, jargon, and creative expression can be found in CIES as part of the undercurrents of contemporary Muslim networks. Content is derived primarily from English and Arabic sources. It is not feasible to monitor Islamic content in all languages, but in the zones that I focus upon, it will be seen that some common issues and themes can emerge from a “snapshot” of Islamic cyberspace.

The Shaping of the Global Islamic Knowledge Economy

The flow of data about Islam that is circulating via the Internet—whether it is the language of slang or the Qur’anic Arabic contained in a sermon—may be appropriate to discuss in terms of a global Islamic knowledge economy. This concept has a link to what Manuel Castells refers to as an “informational economy” in his discussion of twentieth-century global business economics:

There is a strong focus on information and knowledge in CIES, although there can be distinguishing features, too. Ideas of religious knowledge can be quite distinct and authoritative and are utilized by many Muslims—hence the focus on the global Islamic knowledge economy here. While not a business in the sense discussed by Castells, this concept possesses these components and networks of interaction. The linkages are not always transparent, and elements of production, consumption, and circulation take on a religious edge within CIES.

The past few years have been a critical phase in Islamic modern history, a period in which this knowledge economy has continued to evolve. However, twenty-first-century developments are also part of a long-term process of development associated with Muslim networks. To quote from miriam cooke and Bruce Lawrence’s Muslim Networks from Hajj to Hip Hop (2005), one key question is: “How has technology raised expectations about new transnational pathways that will reshape the perception of faith, politics, and gender in Islamic civilization?”8

Islam is being reshaped, and the Internet, in particular the World Wide Web, has had an increasing impact on Muslims in diverse contemporary contexts. It is possible to map and analyze the essential elements associated with the development of Islamic cyber pathways and networks. A broad spectrum of Islamic hypertextual approaches and understandings can be located in cyberspace, created by Muslims seeking to present dimensions of their religious, spiritual, and/or political lives online.

Varied applications of the Internet utilized in the name of Islam may combine websites, multimedia, chat rooms, e-mail listings, and/or various degrees of interactivity. While recognizing that these diverse tools interact, the focus of this book is the World Wide Web. The Web can create online notions of Muslim identity and authority that echo and intersect with similar notions in the nondigital real world, but it also nurtures new networks of understandings in cyberspace.

Muslims have creatively applied the Internet in the interest of furthering understanding of the religion for other believers, especially those affiliated to a specific worldview and, in some cases, a wider non-Muslim readership. It may be a natural phenomenon for a Net-literate generation to seek out specific truths and affiliations online, especially when they cannot be accessed in a local mosque or community context. This reflects Dawson’s point in a discussion on religion and the Internet: “The Internet is used most often to expand people’s social horizons and involvement. People use the Internet to augment and extend their preexisting social lives, not as a substitute or alternative.”9

Empirical evidence also suggests that generalizations cannot be m...