![]()

1 An Essay on the Limits of Religious Thought Written to Prove That We Can Reason upon the Nature of God

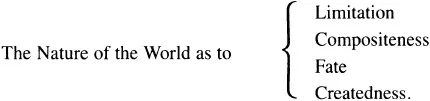

The following is from the first of a group of brief essays, written in the summer of 1859 and unpublished in Peirce’s lifetime. Here he argues that though some notions, such as the idea of God, are literally unthinkable and cannot be immediately present in the mind, they can nevertheless be represented and can therefore be thought of. While this view was not radical, the assertion that thinking can be done in signs was a step along the path to Peirce’s eventual conclusion that all thinking is in signs.

Source: Writings of Charles S. Peirce, 1:37.

What can we discuss? Can we discuss nothing we do not comprehend? Can we not even discuss that which has no existence in nature or the imagination? We can discuss whatever we can syllogise upon. We can syllogize upon whatever we can define. And strange as it is we can give intelligible comprehensible definitions of many things which can never be themselves comprehended.

I will give two instances of this; one simple and the other practical. Suppose somebody should talk about an OG and when you asked him what he meant he should say it was a four-sided triangle. You would proceed to show that he had no such conception that nobody had. You would reason upon that which you could not conceive of. This instance is too elementary. Suppose someone should tell me he could imagine two persons interchanging identities. I should proceed to reason on the pretended imagination and show that it was inconceivable.

![]()

2 [A Treatise on Metaphysics]

If the mind immediately perceives ideas but the ideas are representatives of things without, then the truth of those representative ideas is in doubt. Immanuel Kant had addressed himself to demonstrating, within limits, the truth of perception in his Critic of Pure Reason. Peirce as a teenager had studied Kant assiduously and then, in his early twenties, rejected Kant’s critical transcendentalism as an unwitting return to faith. Peirce preferred to base philosophy on a frank acknowledgment that knowledge always contains an element of faith, an undemonstrable but necessary belief that “the normal representations of truth within us are really correct,” as he says in the following extract from a projected book of which he wrote ten thousand words in 1861. In the three sorts of representation that the youthful Peirce here identifies—copy, sign, and type—he adumbrates his eventual general typology of signs as icon, index, and symbol.

Source: Writings of Charles S. Peirce, 1:72–83.

Introduction

Chapter III On the Uselessness of Transcendentalism

§ 1. The Stand-point of the Transcendentalist

When the view that metaphysics is the study of the human consciousness is carried out in a one-sided way, in forgetfulness that it is as truly Philosophy and also the Analysis of Conceptions, it produces Transcendentalism (better named Criticism), which is the system of investigation which thinks necessary to prove that the normal representations of truth within us are really correct. . . .

§3. On Faith

A. Need of It

I shall show

α. that the Transcendentalists conclude with a return to Faith.

β. that the use they make of it in their own procedure is the source of all that is valuable in their investigations.

γ. that while their own faith is necessarily blind, their reasoning is not so close as to leave no room for demonstrably trustworthy faith.

I. Kant’s Work

An inference is involved in every cognition.

Proof. Relative cognition is the recognition of our relations to things.

All cognition of objects is relative, that is we know things only in their relations to us.

Every cognition must have an object (the subject of the proposition). The faculties whereby we become conscious of our relation to things are known as perceptions or sense.

∴Every cognition contains a sensual element.

Now the information of mere sensation is a chaotic manifold, while every cognition must be brought into the unity of one thought.

∴Every cognition involves an operation on the data.

An operation upon data resulting in cognition is an inference. ∴&c.

This demonstration is extracted from Kant. It does not extend to the cognition “I think.”

Nothing is certain except what rests on the combined testimony of the senses and I think.

Proof. All knowledge, as we have just seen, is an inference from sensual minor premisses. In metaphysics, all inferences have major premisses. All knowledge is inferential except the I think. No cognition is certain which rests only on what is inferential. ∴&c.

Such is Kant’s reasoning. He then proceeds to test all our Conceptions as to objective validity by finding whether they are anything but particular expressions of the I think or of sensuousness. The following he makes objectively valid:—

The Form of the External Sense—Space

The Form of the Internal Sense—Time

The Conceptions of the Understanding

| I | II |

| Of Quantity | Of Quality |

| Unity | Reality |

| Plurality | Negation |

| Totality | Limitation |

| III | IV |

| Of Relation | Of Modality |

| Substantia et Accidens | Possibility–Impossibility |

| Causality | Existence–Non-existence |

| Action and Reaction | Necessity–Contingency |

The following can never enter into any certain thought:—

The Ideas of Reason.

1. The Immateriality, Incorruptibility, Personality, Animality1 of the Soul.

3. God.

α. Though Kant cannot demonstrate the validity of the Ideas of pure reason, yet he chooses to believe it. Although there is not to him one whit more probability that they are true than that they are false, still he trusts in them,—he has Faith.

β. He also takes the validity of sensibility and of the I think for granted. Yet only by doing so has he made any solid work.

γ. A part of his argument is that nothing which rests only on what is inferential can be certain. This is not axiomatic nor demonstrable. It therefore leaves hope of proving the contrary which establishes the validity of faith. . . .

B. Reason of Faith

Unfaith is either total or partial scepticism.

The different faculties have different realms by which they are distinguished. No faculty is to be trusted out of its own realm. ∴Hence no faculty can derive any support from another but each must stand upon its own credibility. No one faculty has more inherent credibility than another. ∴Partial scepticism is inconsistent. Total scepticism condemns itself. ∴Faith is the only consistent course.

The argument has the following advantages.

1. It puts faith on the same ground as all certitude.

2. It does not make it so sure that it is no longer faith.

3. By showing that faith is inherent in the very idea of the attainment of truth, it makes its acceptance axiomatic, and thus explains how we were already sure before we had reasoned about Faith.

C. Nature of Faith

I. What Faith is Not

1. It is not a purely intellectual principle; it is an unaccountable impulse to confide in certain truths.

This is forgotten by those who are over-anxious about the details of evidence in religion. They forget that with the highest certitude of inspiration and of history, belief still depends on an internal impulse. For, some things we should not believe though the angel Gabriel told us, while true religion is instinctively accepted by the ingenuous mind.

2. Faith is not peculiar to or more needed in one province of thought than in another. For every premiss we require faith and nowhere else is there any room for it.

This is overlooked by Kant and others who draw a distinction between knowledge and faith. Wherever there is knowledge there is Faith. Wherever there is Faith (properly speaking) there is knowledge.

3. There is no such thing as having immediate faith in the statements of others, be they men or angels or what. For whenever we believe statements, it is either because there is something in the fact itself which makes it credible or because we know something of the character of the witness. In either case there is a because whose major premiss is some principle concerning general characters of credibility. To believe without any such ‘because’ is mere credulity.

II. What Faith is

1. It is the recognition by consciousness of itself. It is the strength of that faculty by which abstractions are conceived.

2. It is the hearing of the testimony of consciousness, which developes into trust in every man till there is reason for distrust and a spirit of obedience to the Law of God.

3. It is the vigour of that part of the mind which is in communication with the eternal verities. By this, mountains are moved.

III. Effect of faith on Transcendentalism

1. Criticism is entirely swept away as useless.

2. Transcendentalism as a study of the out-reaching of the human mind retains its full value.

3. This study of consciousness is the examination of abstractions by analysis of conceptions.

BOOK I. PRINCIPLES OF METAPHYSICAL INVESTIGATION

Chapter I. Man the Measure of Things

In the Introduction we have considered the Nature of Metaphysics, and have rejected certain false notions of its procedure.

In our investigations, metaphysics is to be taken as the analysis of Conceptions.

We need not ask the critical question; but still there is a question of uncritical transcendentalism with which every method of philosophy must open. It is, How should the conceptions which spring up freely in our minds by virtue of the constitution thereof be true for the outward world?

In this question we detect three leading conceptions Truth, the Innateness of Ideas, Externality. Let us analyze each of these.

§1. Of Truth

True is an adjective applicable solely to representations and things ...