![]()

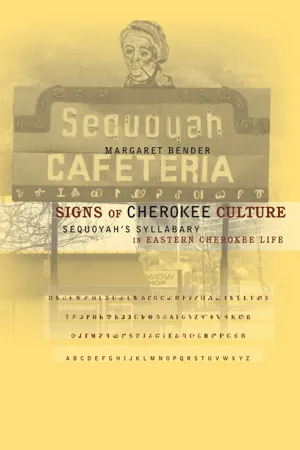

Chapter One: Pride and Ambivalence

The Syllabary’s Received History and Interpretation

The syllabary has never been uniformly seen as a straightforward, innocent, or neutral technology. At its inception, the syllabary was received in a variety of ways by a variety of parties—native speakers, missionaries, and Cherokee and white political leaders. Was it a blessing or a curse? Was it an agent of isolation or a tool for assimilation? Would it facilitate the conversion of the Cherokees to Christianity through the written word or interfere with the efforts of missionaries to teach English and provide a written Cherokee Bible? Would it assist the Cherokees in their quest for progress and development or prevent their access to the best that the civilized world had to offer? The tensions that surrounded its reception and use have not disappeared but continue to reemerge in the writings of historians, anthropologists, and linguists as they seek to categorize the syllabary and to describe its history. These tensions are furthermore evident in the current usage and packaging for tourism of the syllabary by Cherokees themselves, as will be discussed in later chapters. As a fellow anthropologist has pointed out (Terry Straus, pers. com., April 1995), the persistence of a tension or controversy may be a very important cultural persistence indeed. For it is within the parameters of such a conflict, in its terms, that much of what we call “identity” is negotiated.

The history of Cherokee reading and writing in the syllabary provided challenging exceptions to the dominant society’s nineteenth-century rules about the place of writing in white-Indian relations. According to these rules, Native American languages were unwritten (until missionaries or other outsiders developed orthographies for them) and thus were not part of a “civilized” social order.

This dissociation of literateness and Indianness may have a long history. Michael Harbsmeier (1989) has suggested that in the movement of European society toward universal literacy, the production of images of a nonliterate other became necessary. The inhabitants of the Americas, represented in some of the earliest accounts as creating only noise and confusion, gradually came to be seen as having a specifically oral language and culture. This characterization of peoples as oral came to be meaningful only in the context of European self-characterizations as literate.

Peter Wogan (1994) faults historians for taking at face value early modern reports of Native American awe at European writing. Early accounts suggesting that native North Americans considered European writing to be inherently powerful and mystical contain projections, argues Wogan, of European ideologies of literacy onto a constructed oral other. This conception of Native Americans as categorically oral may in part explain the early historical treatment of Cherokee literacy as involving a brief, assimilative burst of energy with the qualities of a miracle and the focus on a few outstanding individuals.

The syllabary’s history challenged this racialized, evolutionary scheme, but it reinforced other components of nineteenth-century literacy ideology. In particular, some aspects of the syllabary’s history were used to support the inherent connection drawn between writing and “civilization.” But while having its own writing system elevated the Cherokee language in many eyes, this fact did not seem to change the basic nineteenth-century American belief in a hierarchy of languages, cultures, and societies. To the extent that they were seen as literate, the Cherokees were no longer seen as Indian by the dominant society.

During the first Bush administration (1988–92), just before I began this project, literacy emerged as a focal point for charitable funding, volunteer action, and legislative efforts in the United States and was a major goal of international development efforts worldwide. But in the context of native North America, reading and writing had long been important symbols of power, progress, and culture. Indeed, writing may be seen as having played a central and formative role in the history of native North America. Treaties, maps, and the changing of official place names have all been means of asserting a new social and political order on the ground through written language.

The syllabary thus stands in a pivotal position—between the reinforcement of a hierarchy and its dismantling; between self-definition and external categorization; between independence and nationalism on the one hand and assimilation on the other. And as this book is intended to demonstrate, the study of writing cannot help but be the study of culture, history, and power.

A Brief History of the Syllabary

In the Cherokee syllabary, each symbol represents a vowel or consonant plus vowel, with the exception of the character

, representing /s/.

1 See Figure 1 for the syllabary chart most commonly used today. Historians generally agree that Sequoyah developed this system in 1821.

According to many accounts (e.g., Foreman 1938; Mary Chiltoskey, pers. com., 1993), Sequoyah recapitulated at least one of the major steps in the “evolution of literacy.” His early attempts at a logographic system were destroyed by a fire. It was then that he reportedly moved on to a phonetic (specifically, syllabic) system. But some accounts suggest that the recapitulation was even more thorough—that Sequoyah started with a pictographic or ideographic system (e.g., see Mooney 1982: 219).2 Once Sequoyah perfected his system, he convinced Cherokee national authorities of its efficacy with the help of his young daughter. Father and daughter, separated so as to be out of earshot of each other, were able to exchange messages via the new writing system. This demonstration, followed by the successful training in the new system of several Cherokee youths, led to the general acceptance of the syllabary (Foreman 1938: 25).

Once the syllabary became public knowledge, literacy reportedly spread quickly, to the extent that a majority of the Cherokee people were literate in it within months. Cherokees began using the new writing in personal correspondence, to translate portions of the Bible, to produce notebooks of medicinal texts, and for record-keeping and accounting. Political leaders, who had made use of translators to record their proceedings and correspondence in English, were now able to produce government documents in Cherokee. With the establishment of a Cherokee printing press came the publication of the Cherokee New Testament and a newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix.

Despite the violent interruption created by the forced removal of most Cherokees to Indian Territory in 1838, newspapers, religious materials, and political materials were printed throughout the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, however, less material was printed in Cherokee, probably in large part because of the change in status of the Cherokee Nation with the creation of the state of Oklahoma in 1907. Handwritten materials continued to be produced.

In the 1960s there was a resurgence of interest in Cherokee printing (White 1962); at that time, some Oklahoma Cherokees participated in the Carnegie Project, a native language literacy and education project administered by the University of Chicago (Tax and Thomas 1968). This project directly produced a variety of informational and educational texts in Cherokee; indirectly, it may have provided the impetus for the use of the written language in a variety of symbolic contexts.3 In the mid-1970s, within a year of each other, a dictionary and beginning textbook were published in Oklahoma (Feeling 1975; Holmes and Smith 1977). At the same time in North Carolina, a linguist and an anthropologist produced a grammar and a dictionary of Eastern Cherokee (Cook 1979; King 1975). Bilingual education programs were started in both the East and the West. The technology associated with the syllabary continued to grow, and an IBM Selectric ball was developed for the syllabary and, ultimately, computer fonts.

In sum, Cherokee literacy has been a dynamic phenomenon, associated with changing institutional associations, technologies, and contexts of usage.

Suspicion, Pride, Civilization, and Nationalism: The Reactions of Sequoyah’s Contemporaries

A story that appeared in the Cherokee Advocate, a newspaper printed in the postremoval Cherokee Nation, gives us some sense of how Sequoyah’s invention was originally received:

James Mooney, who collected myths among the Eastern Cherokees during the 1880s, did not hear this story told himself, but, noting that both Daniel Butrick and Elias Boudinot4 recorded similar tales, says he believes the story to be a popular one. Mooney reproduces the following, which Butrick obtained from an elderly Cherokee: “God gave the red man a book and a paper and told him to write, but he merely made marks on the paper, and as he could not read or write, the Lord gave him a bow and arrows, and gave the book to the white man” (Mooney 1982: 483). Mooney also quotes Boudinot as follows: “They have it handed down from their ancestors, that the book which the white people have was once theirs; that while they had it they prospered exceedingly; but that the white people bought it of them and learned many things from it, while the Indians lost credit, offended the Great Spirit, and suffered exceedingly from the neighboring nations; that the Great Spirit took pity on them and directed them to this country” (Mooney 1982: 483). This story of the book and the bow had fallen out of circulation by the time Mooney arrived in western North Carolina. One might reasonably propose that the story was rendered obsolete by the invention of Sequoyah’s syllabary. The poignancy of the story is somehow lost once the Indians have regained what was truly theirs to begin with. But it seems possible that a narrative could outlive technological obsolescence if it continued to fit into or support a specific cultural framework. If the narrative of the book and bow were read today, a second reversal would be implied; the Indians, having once lost what was theirs, have gained it back in spectacular fashion.

Perhaps the narrative of the book and the bow would have endured if it had reverberated with later Cherokee beliefs about the syllabary and about each people. But in fact, there are incongruities between the associations the syllabary has taken on in historical accounts, accounts by linguists, and accounts among the Cherokees themselves, and the associations it has in the versions of this narrative.

First, the narrative implies that reading and writing are, or were at one time, the natural gifts of the Indian. The prevailing beliefs about Sequoyah and the syllabary, however, posit the invention of the syllabary as a true miracle; many see it as a supernatural event of the highest order.5

Second, it implies a uniformity of “the book.” The Indian had “it,” then the white man stole, bought, or was given “it.” From the very beginning, the new Sequoyan reading and writing was seen as very different from, and much more Cherokee than, the white man’s reading and writing. (In Cherokee, the words for white man and the English language are related or, for some speakers, the same: yu:ne:ka or yo:ne:ka. To read English is thus to read “white.”)

The first and third versions of the narrative also imply that reading and writing are fairly easy, that one must only have “the book” to be literate. In the early days of the syllabary’s life, it does indeed seem to have been seen as miraculously easy to learn. Cherokee children who took up to four years to read and write English reportedly learned the syllabary in a few days and put it to use. But the reputation of the syllabary has changed considerably in the last 170 years so that it is now considered by many native speakers to be an extremely difficult writing system to learn and use. Depending on when this shift started taking place (and whether, in fact, all Cherokees ever saw the syllabary as easy), this may be another area of discord between the narrative and contemporary perceptions.

There is one area in which the narrative does reverberate with postinception attitudes. The story was told to Sequoyah by his contemporaries, according to the Cherokee Advocate, to dissuade him from his project and to cast suspicion on it. Although the book was a gift from the Creator intended for the Indian, according to the narrative it has since entered the exclusive purview of the white man. The implication seems to be that there is something unnatural about Indians possessing the book. Yet that implication would seem to be in tension with the narrative’s assertion that the book was the Creator’s gift to the Indian in the first place. This tension between the perceived appropriateness and inappropriateness of Indian writing has colored the syllabary’s history and can still be glimpsed today in local ideologies of literacy and in the treatment of the syllabary in the context of tourism.

The plural associations of the syllabary have always stood in tension with each other—both suspicion and pride have shadowed it. During the process of invention and afterward, the syllabary has been associated with traditional medicine and spirituality as well as with Christianity, and both have provided contents and contexts for its use. Sequoyah was reportedly accused of witchcraft while working on the syllabary, but once the system was developed, it was quickly put into use by both missionaries and traditional medical practitioners or conjurers.

Ultimately, then, the story of the book and the bow has been eclipsed by one much more complex. The narrative justification for why Indians do not write has been replaced by the story of the writing Indian. The original story of the book has been replaced by the story of Sequoyah.

It is fitting that this new, mysterious story of the book, the Sequoyah story, has been passed down in large part through the written, rather than the oral tradition. When I asked North Carolina Cherokees if they had heard any stories about Sequoyah, his life, or the invention of the syllabary, they usually said they had not. What they did know they told me they had gathered from the written accounts that began almost simultaneously with the emergence of the syllabary itself, which created an international sensation in the 1820s.

This story has become a legend itself, and it is shrouded in mystery. The firsthand accounts of Sequoyah are vague in both content and origin. Many of the early written descriptions of Sequoyah seem to be based on a supposedly firsthand account that appeared in the Phoenix by G.C., an unknown author. When John Howard Payne6 tried to interview Sequoyah, his interpreter would not provide simultaneous translation, saying that he did not want to interrupt the flow of the great man’s thoughts. The next day, Sequoyah said he did not want to repeat his story because his faulty memory might get him in trouble (Foreman 1938).

Fogelson’s analogy is a powerful one, since most Eastern Cherokees today see both Sequoyah and Jesus as important sources of “the word.”

The etymology of Sequoyah’s name is even a source of mystery. Interpretive translations range from “he guessed it” to “pig in a pen” (Kilpatrick 1965: 5); unlike many Cherokee names, this one does not enjoy an obvious, universally agreed-upon meaning. Jack Kilpatrick has also suggested that the name is a foreign borrowing (1965: 5).

Sequoyah’s background has also been the subject of debate. Some authors make much of his mixed parentage, insisting that his father was the white trader and friend of George Washington, Nathaniel Gist (Foreman 1938). Others have denied not only Sequoyah’s white ancestry but also the notion that he invented the syllabary at all. Traveller Bird (1971) in particular has argued that the syllabary was invented by another tribe before contact and perpetuated by means of a secret society to which Sequoyah belonged. The syllabary’s very genesis, then, is a source of conflicting interpretation.

Even according to the version of events that identifies Sequoyah as the syllabary’s inventor (all published accounts, essentially, except for that found in Traveller Bird 1971), the Cherokee writing (now called Sequoyan by some) emerged out of circumstances that seemed suspicious at the time. Sequoyah’s motives and intentions were questioned; as mentioned above, many accused him of witchcraft.7 His wife’s relatives reportedly burned down the hut containing his earliest efforts, interpreting his obsession as, at the very least, an abandonment of his responsibilities. As one of my consultants8 told the story, “He was half Chero...