![]()

1. Where Winds Gather

Every street was impassable, every roof was gone, every lane closed up, shingles and immense pieces of wood, stone, and bricks were knee deep in the streets . . . . The greater number of the houses were levelled with the earth or unroofed; the largest trees were torn up by the roots, or their branches were twisted off them. . . . The wind rushed under the broad verandahs, tore off the roofs, demolished the walls, and the pillars were levelled in rows. . . . The country villas were no more, and the once beautiful and smiling scenery was now also gone. No vestiges remained of the woods and the groves of palms, and even the soil which produced them was washed away; almost all the public buildings were razed to the ground.

James E. Alexander, Transatlantic Sketches (1833)

Parents beheld their children, and children their parents, husbands their wives, and wives their husbands, buried in the ruins, or strewn around them disfigured corpses; others, with fractured limbs, and dreadful mutilations, were still alive, and many of them rescued from under the fallen buildings; and it was dreadful to hear their heart-piercing cries of agony. Many streets in the town were totally impassable, from the houses having been lifted up from their foundations, and thrown in one mass of ruins into the roads. Masses of rubbish, broken furniture, ships spars, packages of merchandise, huge blocks of mahogany, seemed to have been washed up, and carried by the wind or the tide to great distances, so as completely to block up the streets and highway.

Andrew Halliday, The West Indies (1837)

The tempest rages with such fury that trees are uprooted, buildings thrown down, and ships lifted high on the beach. So vivid and incessant is the lightning that the whole heavens seem in conflagration; appalling thunders mingle their stormy music with the roar of the waves, the shriek of the winds, and the frantic cries of those are in expectation of almost immediate death. The roof of a house may be torn away, and its doors and windows be driven in, yet there is little hope of safety in flight, for there is danger being blown over a precipice, or struck by the boards and shingles, which are drifted to and fro as if they were light as threads of gossamers. . . . The island from end to end is one scene of desolation. . . . Cane fields and provision grounds are as thoroughly devastated as if a troop of wild elephants had rushed over them.

Jabez Marrat, In the Tropics (1884)

It is not given to the pen, Your Excellency, to paint with such frightful colors the terror experienced on that horrible night.... I know of no other instance of inhabitants drowning in their own homes as a result of water driven by the wind through the doors, windows, and the roofs, whose tiles flew about like feathers. Many fled into the streets, envisioning their imminent death by being buried alive in the ruins of their homes or drowning by the raging waves of the sea that invaded the town, carrying their children in desperate search for another place of shelter. . . . The scene we confront is one of anguish and widespread destitution.

Manuel de Mediavilla, Cienfuegos, to Governor General (June 8, 1832)

The winds originate from the eastern waters of the Atlantic, from somewhere on the vast oceanic expanse between the Cape Verde Islands and Barbados, at the point where the prevailing northeasterly breezes above the equator converge with southeasterly breezes from below the equator. The strongest winds begin to stir during the months around the autumnal equinox, the time of the equatorial doldrums, in the still region of moist air between the steady trades. Catastrophic winds begin as calm air.

The still air, well moistened by evaporation, starts to churn under the strong sun, becoming unstable and unpredictable, forming low-pressure systems by which the warm air is driven inward and upward by convection into cooler zones, there to spiral and swirl. Warm vapors rise and in the process cool and condense into billowing clouds. Evaporation and conduction transfer immense quantities of heat and moisture into the atmosphere and eventually give definition and direction to the mass of moving air.

The churning winds migrate westward, driven by trade winds, often on a journey of thousands of miles, over many days—sometimes weeks, gaining momentum and velocity as they draw strength from warm moist air pulled over the tropical waters. Bands of squalls and thunderstorms swirl in alignment with the direction of the winds, often three hundred to four hundred miles in advance of the approaching center. It is possible to speak broadly of a corridor extending from longitude 56° west to 96° and from latitude 10° to 30° north—the area otherwise known as the Caribbean Sea—and extending upward into the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean, over which these winds most frequently traverse the New World.

/ / / / /

The signs of approaching winds assumed recognizable form for early European settlers in the Caribbean, for in these times all that was available were signs. First, there was a stillness in the air, experienced as moisture-laden air and as a sultry, heavy atmosphere. Breezes began to stir often days in advance, shifting daily as erratic movement from land to sea and back again. Falling temperatures were at times accompanied by indigo blue skies. Winds pushed in their advance long rolling waves, often a thousand miles ahead of the center, at speeds slightly less than the velocity of the winds that produced them. Then there appeared the unmistakable signs: a thin cirrus haze, followed by the true cirrus: magnificent clouds shaped as long white feathery plumes brushed across a clear azure sky—a phenomenon early associated with approaching atmospheric mass—and often converging to a point on the horizon suggesting the center of the approaching disturbance. Solar and lunar haloes often accompanied the cirrus haze, mostly as spectacular crimson skies at sunrise and sunset.

The early Europeans quickly learned to divine the meaning of these signs. Information was obtained first from Native Americans. Colonists in St. Christopher, wrote John Oldmixon in 1708, were tutored by one elderly Indian in the “Prognosticks to know when a hurricane was coming”:

The winds reached the Caribbean mostly in August, September, and October—although they were known as early as June and July or as late as November—entering through well-defined paths, usually by way of the northern Windward Islands, moving at a speed of 12 to 15 miles per hour. By this point they may well have expanded to a radius exceeding hundreds of miles, driven by counterclockwise winds attaining sustained velocities between 75 and 150 miles per hour, sometimes more. The course as well as the intensity of the winds generally coincided with the season. Early in the summer they recurved northward out of the western Caribbean. In August and September the winds typically swept in a northwesterly direction through the eastern Caribbean; in October they roared northward over the waters and islands of the southern Caribbean. Their frequency varied from year to year: sometimes there were as few as one or two a year, sometimes none; other times as many as ten to fifteen.2

They may have been unexpected, but they were not unfamiliar, and the arrival of each new season raised a specter of danger looming just beyond the horizon. A brooding disquiet descended on the Caribbean in anticipation of the destructive fury of the winds from the east. It has always been thus, since the Native American peoples dispersed among wide-flung islands of the Caribbean archipelago.

/ / / / /

The word huracán passed into the Spanish vernacular from indigenous usage. The Taíno Indians used “huracán” to mean malignant forces that took the form of winds of awesome proportions and destructive power, winds that blew from all four corners of the earth. The word was found in a variety of derivative forms, including hunrakán, yuracán, yerucán, and yorocán, and appeared in use among the pre-Columbian peoples of Mexico, Central America, and the northern coast of South America. All forms signified the name of a malevolent god, possessed of the capacity to inflict immense destruction.3 Among the Maya, hurakán was the name of one of the mightiest gods; hurakán, cabrakán (earthquake), and chirakán (volcano) constituted the three most powerful natural forces in the Mayan culture.4

Among the Taíno in the Caribbean, “huracán” was the name of a powerful demon given to periodic displays of destructive fury. Indeed, the Taíno explanation of the creation of the Antilles held that huracán had shattered the coastline of the mainland and subsequently scattered the land fragments into the Caribbean archipelago.5 Hurakán was one of the principal deities of the pre-Columbian pantheon, to be periodically placated, typically by ritual supplication of music, song, and dance. In Historia general y natural de las Indias, isla y tierra firme de la mar océano (1535), one of the earliest European accounts of the indigenous population of the Caribbean, chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, who resided in the Caribbean intermittently between the 1510s and the 1530s, wrote of the terror inspired by huracán: “[T]he way the devil . . . is depicted assumes a variety of colors and ways. When the devil wishes to frighten [the Indians] he threatens them with huracán, which means storm. These storms are so fierce that they topple houses and uproot many large trees.... [I]t is a frightful thing to see, which without doubt appeared [to the Indians] to be the work of the devil.”6

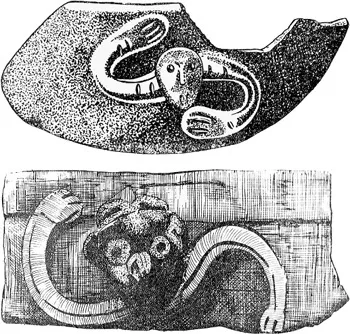

Taíno images associated with the representation of hurricanes. The similarity to the modern meteorological icon of the hurricane is suggestive. Reprinted from Fernando Ortiz, El huracán: Su mitología y sus símbolos (Mexico, 1947).

One of the earliest known European uses of huracán appears in Pedro Mártir de Anglería’s 1511 chronicle Décadas del Nuevo Mundo. He wrote of “a monstrous whirlwind [inaudito torbellino] from the east that lifted even the heavens” and continued:

Huracán, acknowledged explicitly as a word of Indian origin, also appeared in the Historia de las Indias by Bartolomé de las Casas, published in 1575. “At this time,” Las Casas wrote of a storm in 1495, “four ships . . . in the port were lost in a great storm, what the Indians called in their language huracán, and which we now also call huracanes, something that almost all of us have experienced at sea or on land.” Fernández de Oviedo observed firsthand what the Indians meant by huracán and recorded the episode in his chronicle. “Huracán, in the language of this island,” he wrote, “properly means an excessively severe storm or tempest; for, in fact, it is nothing other than a powerful wind and an intensive and excessive rainfall, together or either one of these two things by itself.” Oviedo added: “No one on this island who lived through these storms will ever forget the experience.”8 Pedro Simón discovered the word “huracán” in use among Indians on Tierra Firme. “In the language of these regions,” Simón recorded, “the wind is called huracán, from which the Spaniards took the word, improving the vocabulary to call the turbulence of winds huracán. ... Every effort was made to learn the language of the Indians with whom they deal, committing to memory among others this word huracán and what it signified, and they used it to refer to tumultuous winds.”9 The word “huracán” appears to have obtained English language usage for the first time in Richard Eden’s 1555 translation of Mártir de Anglería’s account as “furacanes,” and it appeared during the next one hundred years in various forms—including “herycano,” “furicano,” “hericano,” “huricano,” “heuricane,” and “hurican”—before assuming its present form, “hurricane,” in the late seventeenth century.10

/ / / / /

Before hurricanes passed into the realm of the European familiar, they dwelled in a place of fear and foreboding. Certainly Europeans before Columbus had direct knowledge of storms. The mariners and maritime merchants of the Mediterranean had accumulated a vast store of infor...