![]() PART I

PART I

THE SEA NARRATIVE AND SAILORS’ LITERARY CULTURE![]()

1 THE LITERATI OF THE GALLEY

The naval memoir Life in a Man-of-War, published anonymously in 1841, provides a witty account of a cruise in “Old Ironsides,” or the legendary warship Constitution. Rather than an account of military exercises or engagements, though, Life in a Man-of-War presents a cultural history of shipboard life in the American navy. The narrator, working in a self-described “scribbling vein,” aims to document—in “the rude, unpretending, and unpolished style” of a common sailor—the “disquietudes, delights, sorrows, joys, troubles, and perplexities” of the naval service.1 The narrator’s avowed lack of literary pretension is a conventional move, certainly. His confession to a “scribbling” urge aligns him with other nineteenth-century would-be authors who felt the itch to write in a market that could newly accommodate literary amateurs.2 Yet his self-deprecating gesture toward the conventions of narrative writing does not deny this sailor literary authority. “Nothing is lost on him that sees / With an eye that feeling gave,” the epigraph to Life in a Man-of-War reads; “For him there’s a story in every breeze, / A picture in every wave.”3 Sailors may joke and lark, the narrative suggests, but they still are part of a broader fraternity of feeling.

Early in Life in a Man-of-War, the reader is invited to survey the groups of sailors who congregate on the decks in their time of leisure. The narrator is presumably a member of this crew, for the memoir is credited only to “a fore-top-man,” or a common sailor who works high in the foremost mast. Among those engaged in sewing or napping, one group of idlers in particular stands out. The narrator, shifting his prose account into verse form, calls attention to

A literary group of three or four,

Discussing the merits of some novel o’er

“Have you read Marryatt’s Phantom Ship all through?”

Eagerly asks one of this book-learned crew:

“I have,” is the reply, “and I must own,

In my opinion it has not that tone

Of interest—nor the language half the zest

Of Simple, Faithful, Easy, or the rest.”4

This discriminating sailor critiques the work of the popular British sea novelist Frederick Marryat (or Marryatt, in its common misspelling), whose best-known novels Jacob Faithful, Peter Simple, and Midshipman Easy are referenced here. But a fellow member of what the narrator elsewhere calls “the literati of the galley” becomes indignant at the sailor’s analysis and replies with spirit: “I’m sure I never thought ’twould come to pass / Have Marryatt’s works reviewed by such an ass.”5 What is notable about the literary debate staged in Life in a Man-of-War is that the terms of the conflict lie not in questions about the novels’ accuracy or seamanship but instead in their literary value: their tone, their use of language, their aesthetic concerns. The literary taste displayed by the sailors functions as a comic element of the memoir, in part, since seamen have traditionally been overlooked in the broader community of readers. But the joke is not wholly on this “book-learned crew.” Life in a Man-of-War is one of scores of seamen’s narratives that assiduously cataloged the ways in which sailors participated in the production and dissemination of literature, as well as its consumption.

Indeed, the reading communities of nineteenth-century American seamen were lively yet discriminating. The books they read at sea, the methods they used to acquire books, and sailors’ own engagement with the print public sphere constitute the focus of this chapter. What follows serves as an overview of seamen’s literary culture in antebellum America, one that aims to contextualize the more specific focuses of subsequent chapters. Instrumental in a vibrant circulation of books in the oceanic world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sailors produced, traded, gambled for, and retold a diverse body of printed works. This market was well documented in, and in part constituted by, the sailors’ own writing. Their narratives detail what their fellow seamen were reading and which books especially appealed to their interests. Forming their own literary coteries, sailors were attentive to the popular books of the day. These works—including the novels of Cooper, Scott, Bulwer-Lytton, Marryat, and Godwin as well as travel narratives, conduct manuals, reform tracts, “flash” papers, pamphlet novels, and other ephemeral works—were invoked and analyzed within sailors’ narrative accounts of their maritime experience. In citing works that would likely be familiar to nonspecialist readers of sea narratives, too, sailors were able to stake out their relative interests, terms, and circulation within the broader literary world. Books at sea were not only designated for private use but shared among fellow crewmen and exchanged with other ships. Many sailors recount such trades, such as when Richard Henry Dana describes a typical visit with another ship’s crew: “We exchanged books with them—a practice very common among ships in foreign ports.”6

Sailors’ participation in broader literary culture was peculiar, however, in the same way that sailors’ status as wage laborers was peculiar: both were in thrall to old and new orders of production.7 Historians of reading practices have argued that early American reading was intensive—that is, households owned few books, but those books were read again and again. As advancements in book production and circulation made printed works more affordable and more widely available, reading became extensive—readers might read a far greater number of works but would know each work less intimately.8 By necessity, American sailors were engaged in intensive reading practices, even though they lived in an age of rapidly expanding print possibilities. J. Ross Browne’s narrative of his whaling voyage mentions on several occasions that he “read and re-read” the stock of books on board ship “till I almost had them by heart.”9 Dana’s narrative confirms that the opportunity to trade books with sailors on other ships is eagerly seized because of the chance to “get rid of the books you have read and re-read, and a supply of new ones in their stead, and Jack is not very nice as to their comparative value.”10 Given the limited stock of books aboard ship, reading became automatically intensive and collective, as literate sailors shared a common body of texts.

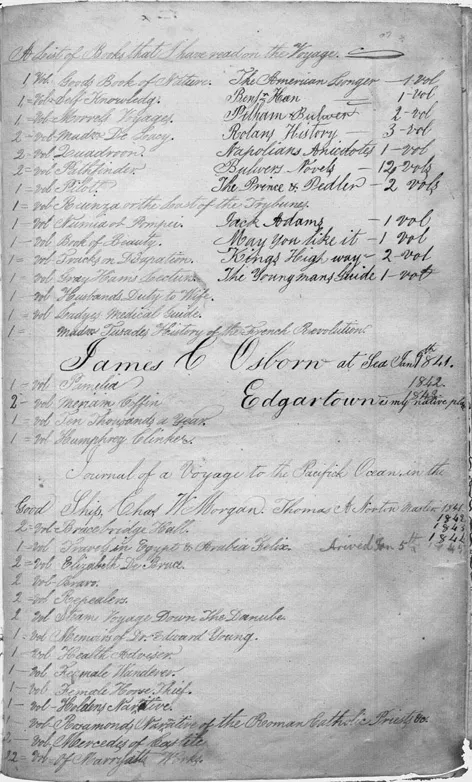

Yet despite the fact that sailors’ reading practices tended to reflect older modes of consumption, reading at sea nevertheless was encouraged by technological and economic advancements in the world of print in the first half of the nineteenth century. Transformations in the mechanics of printing made mass production of literature possible, lowering costs and making a broad array of published works available to the reading public. The diversity of works aboard any given ship, both in content and in class, testifies to this effect of modernization. A list of the books Browne read while at sea, for example, includes his shipmates’ hoards: “The cooper’s stock of literature consisted of a temperance book, a few Mormon tracts, and Lady Dacre’s Diary of a Chaperon.” Further, Browne records, “one of my shipmates had a Bible; another, the first volume of Cooper’s Pilot; a third, the Songster’s own Book; a fourth, the Complete Letter Writer; and a fifth claimed, as his total literary stock, a copy of the Flash newspaper, published in New York, in which he cut a conspicuous figure as the ‘Lady’s Fancy Man.’ I read and reread all these.”11 Ranging from etiquette books to religious writing, from racy flash papers of the urban underworld to Cooper’s popular sea novel, this catalog shows both the hunger and the range of seamen’s participation in literary culture, as well as their class aspirations. Furthermore, the presence of temperance materials and religious tracts reflects the influence of charitable reform movements, many of which saw mariners as a special object of attention after the 1820s. Other sailors recall similarly extensive shipboard libraries, whether collected centrally or passed around informally. C. S. Stewart appreciated having an official ship’s library “for the recreation and improvement of the crew.” In the first month of his naval service, Stewart records having read “Irving’s Life of Columbus, Scott’s Napoleon, the Lady of the Manor, Erskine’s Freeness of the Gospel, Weddell’s Voyages, Payson’s Sermons, and Martyn’s Life.”12 A comparable range of reading interests is displayed in the list of books read by James C. Osborn, the second mate of the whaleship Charles W. Morgan, as recorded in the ship’s log. It includes many popular novels such as Pamela, Humphrey Clinker, The Pathfinder, The Pilot, and twelve volumes of Bulwer; travel narratives identified as Steam Voyage down the Danube, Travels in Egypt and Arabia, and Morell’s Voyages; and temperance tracts and conduct manuals, including “Tracks on Disapation” [sic], “Husbands Duty to Wife,” “Health Adviser,” and Alcott’s “Young Man’s Guide” (see fig. 1.1).13

While Browne, Stewart, and Osborn faced limitations in the total amount of written material available to them at sea, it should be clear from the above examples that they were not limited in terms of the variety of genres of reading material. The range and diversity of materials to which sailors had access reflect the contingencies of shipboard reading, as well as its expansive possibilities. For the democratization of reading and writing should include sailors, their own works argued. When the narrator of Life in a Man-of-War, for one, announces that he will describe his fellow shipmates as “Literary Tars,” he anticipates that the title would generate some criticism:

Methinks I hear you with a pish exclaim, “Literary Tars—quotha, upon my word the Belles Lettres are becoming fearfully defiled, when the wild, reckless sailor, ruffles the leaves with his clumsy and tar-besmeared fingers.” But the bard of Avon says . . . that “there are water rats as well as land rats;” why then should it be considered a strange or unaccountable coincidence if we had our book-worms on the forecastle of a tight Yankee frigate, as well as in the boudoir or the drawing-room.—The “march of mind” is abroad, and making rapid strides in both the hemispheres; why then should it not on its journey take a sly peep amongst the worthies of a man-of-war?14

Literary practices are staged in the forecastle as well as in the drawing room, the narrator insists. And as recruits in the “march of mind,” he further implies, sailors should write and circulate their own works, not merely consume the works of others.

Sailors were keen to show that the typical Jack Tar should not be thought of as “a mere machine,—a mass of bone and muscle.”15 As the whaling voyager William Whitecar found, his fellow crew members were not reflexive machines but were instead “thoroughly conversant with the leading topics of the day, and each, like every true American, had his individual opinion of the merits of newspaper notorieties, politics, and other matters that engross the American mind.”16 The “matters” that engage opinionated sailors, Whitecar stresses, are not particular to their trade. Reformers took up this line in their mission to improve the moral and spiritual condition of sailors; as one wrote, “The class of youth from which it is proposed to raise up an efficient marine, are imbued with a passion for the sea, and are generally above the average of mind, education and social position. . . . The ocean is adapted to high intellectual, social and moral development. First, the employments of the sea demand skill, ingenuity and intellectual ability, in a far greater degree than the purely mechanical employments on shore. Next, a well regulated ship affords ample opportunity for intellectual and social culture.”17 Both sailors and the reformers who targeted them benefited from this approach. The charitable attention devoted to seamen complemented the broader culture of reform that characterized antebellum society, in its interest in increasing literacy, sobriety, and piety among workingmen. In turn, sailors were esteemed for their “skill, ingenuity and intellectual ability,” which fit within their own conception of their mechanical and imaginative facility.

Still, the Atlantic and Pacific worlds of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries presented much for sailors to think about. While maritime laborers were, by definition, itinerant agents in international trade, the immediate circumstances of their work aboard ship meant that their daily lives were characterized by confinement and circumscription rather than mobility. Furthermore, the “imaginative communities” created by the rise of nations and of nationalism in the Ages of Enlightenment and Revolution, to use Benedict Anderson’s familiar description, did not always encompass sailors. That is, in an era of impressment and state-sponsored and renegade piracy, sailors who claimed national affiliation or protection found their appeals routinely disappointed or disavowed.18 Paul Gilje takes up one aspect of this paradox in his illuminating meditation on the meaning of “liberty” to antebellum American sailors. Although sailors accepted revolutionary ideals of freedom, the notion of liberty that had the most immediate relevance for them was the concept of liberty as shore leave, which translated as the freedom to drink, carouse, and burn their wages.19 Both Gilje’s work on sailors in the Revolutionary War and Michael J. Bennett’s examination of Union sailors in the Civil War find that the multiracial and multinational crews aboard U.S. ships made national ideology and identification more the work of commercial or personal advantage than of patriotism.20 When sailors did take a more explicit interest in political or national affairs, they focused on causes near to them. Barbary captive William Ray, for one, compared American sea captains to the despots of North Africa, while other sailors protested the practice of flogging by invoking American chattel slavery.

FIGURE 1.1: “A List of Books that I have read on the Voyage.” This list is included in the logbook of the whaleship Charles W. Morgan by James C. Osborn, the twenty-six-year-old second mate of the ship; Osborn recorded the books he had read in the course of the Morgan’s multiyear cruise. (Log 143; Logbook, 1841–1845, Charles W. Morgan [Ship: 1841], 185; © G. W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Conn.)

Nevertheless their class status was the issue of most concern to sailors, as Marcus Rediker, in his influential study of early-eighteenth-century Anglo-American seamen, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, has most ably demonstrated in his labor history of maritime collectivity.21 And their literary efforts, sailors were aware, would be evaluated in terms of their position as laborers. Indeed, seamen were conscious of their standing to a notable degree. George Little, for one, much lamented the fact that few of his countrymen considered “the relative importance of seamen, either for the advancement of commercial pursuits, or for the protection of our country’s rights, or for the maintenance of our national honor.” Little found that most did not realize that “seamen are the great links of the chain which unites nation to nation, ocean to ocean, continent to continent, and island to island.”22 Little’s conclusion here may seem perverse: he stresses the exemplary nationalism of sailors while simultaneously dissolving their national identification in favor of an affiliative chain that could figuratively link continents, seas, and countries. Yet he salutes seamen’s position as workers whose value was both material and symbolic. That is, sailors had two functions in the nineteenth-century maritime world: for one, in the time before steamships, sailors’ bodies were the engines...