![]()

PART I

Protestant Germany:

The Seventeenth-Century Antecedents and Origins

![]()

CHAPTER I

The Lutheran Historia and Passion

The Lutheran Historia before Schütz1

The Latin word historia, or the German Historie, when first used as a term in the Lutheran church, generally designated a biblical story. By the late sixteenth century the term was also applied to a musical genre that used a biblical story as its text, nearly always in German. The genre itself dates from the earliest decades of the Lutheran Reformation and represents a continuation and further development of Roman Catholic practices of singing the Passion. The text of a musical historia consists of a story either quoted from one of the Gospels or compiled from the four Gospels. The latter type of text, called a Gospel harmony, is the one most often found. Even when the title of a Passion historia states that the text is from one of the Gospels, the work often includes a Gospel harmony near the end in order to present the seven last words of Christ, since no single Gospel includes all seven. The only portions of a historia text that are not quoted from the Gospel story are the exordium and conclusio—that is, the introductory and concluding passages. The story of the Passion is the most common one for historiae; that of the Resurrection is next most common. Other stories, such as that of the Nativity or of John the Baptist, are rare. A significant influence on the texts of Passion and Resurrection historiae was the “harmonized” version of these stories published by a theologian and colleague of Luther, Johann Bugenhagen, under the title Die Historia des Lydens und der Auferstehung unsers Herrn Jhesu Christi aus den vier Evangelisten (“The Story of the Suffering and Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ from the Four Gospels,” Wittenberg, 1526). This work was often reprinted and was widely read in Lutheran churches in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

The musical recitation of the Passion story had been an important feature of the Mass during Holy Week in the pre-Reformation church; the Passion historia continued this function in Lutheran church services. Historiae on the subject of the Resurrection, and probably those on other subjects except for the Passion, appear to have been performed during vespers.2

In their musical settings the historiae may be classified as responsorial, through-composed, or a mixture of these two types.3 The responsorial, derived from the most common type of Passion setting in the Roman Catholic church, is by far the most significant; it was the earliest, remained in practice the longest, and exerted the strongest influence on both the oratorio Passion, which culminated in the Passions of J. S. Bach, and the German oratorio. Less closely related to the oratorio are the through-composed and mixed types, characteristic only of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

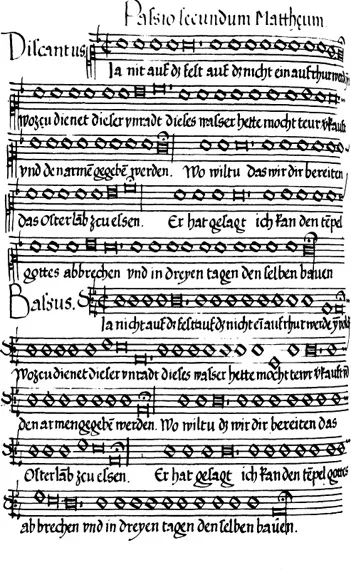

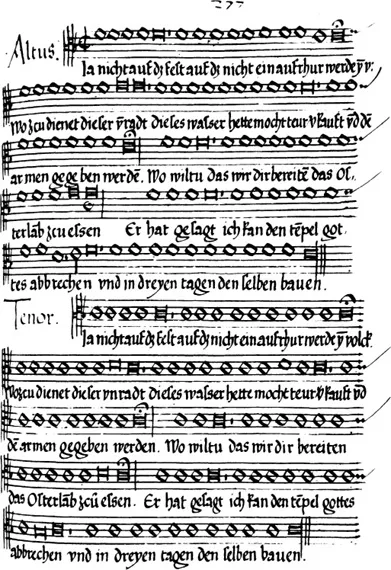

The earliest Lutheran responsorial historia, a St. Matthew Passion by Johann Walter (1496–1570), dates from about 1530.4 As is characteristic of this type, the parts of the individual personages are set to plainsong recitation tones and are sung by three soloists (the Evangelist, T; Jesus, B; all other personages, T), and the parts of the turbae—such as the Disciples, the Jews, the High Priests, and the Soldiers—are set for chorus (SATB). These choral sections are in falsobordone, an extremely simple note-againstnote style with no polyphonic elaboration. This Passion by Walter was a model for numerous other sixteenth- and seventeenth-century works, including an anonymous St. Matthew Passion (attributed to Walter) in a manuscript of 1573 and the St. Matthew Passions by Jakob Meiland (1570), Samuel Besler (1612), and Melchior Vulpius (1613).5 These works tend to retain Walter’s procedures for the soloists but provide more elaborate choral numbers.

Of the responsorial historiae on subjects other than the Passion, the earliest is an anonymous setting of the Resurrection story from about 1550.6 This work is much like Walter’s Passion in that the individual personages are sung by soloists to recitation tones (the Evangelist, T; Jesus, B; Mary Magdalene, S; and the Angel and Cleophas, T) and the parts of two or more personages are sung by the chorus in falsobordone. Another example of a Resurrection historia, using similar material for the soloists but more elaborate choruses, is Nikolaus Rosthius’s Die trostreiche Historia von der fröhlichen Auferstehung unsers Herrn und Heilandes Jesu Christi (“The Comforting Story of the Joyful Resurrection of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ,” 1598).7

In through-composed historiae the entire text is set polyphonically. Such works vary stylistically from falsobordone to a contrapuntal motet style, with the individual personages either not distinguished musically from one another or distinguished only by various groupings of voices. Thus the through-composed historia is less realistically dramatic than is the responsorial type, and for this reason the former is less closely related to the oratorio. The through-composed type of setting was occasionally used for Roman Catholic Passions in sixteenth-century Italy,8 but it was much more prominent in Lutheran Germany. Particularly important for its influence on the Lutheran through-composed historia is the Latin Passion printed by Georg Rhaw in 1538 under the name of Jakob Obrecht but attributed in earlier Italian manuscripts to

FIGURE I-1. The first four choral sections, in falsobordone style, of Johann Walther’s St. Matthew Passion, from the choirbook manuscript at Gotha. The manuscript does not include the plainchant parts for the soloists. (Reproduced by permission of D-ddr/GOl: Chart A 98, fols. 276v–277r.)

Antoine de Longueval (or Longaval).9 This work, still widely performed in Lutheran Germany in 1568,10 is based chiefly on the Passion according to St. Matthew; it also draws on the other Gospels in order to include the seven last words of Christ. Particularly noteworthy among the through-composed historiae of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries is Leonhard Lechner’s Historia der Passion und Leidens unsers einigen Erlösers und Seligmachers Jesu Christi (“Story of the Passion and Suffering of Our One Redeemer and Savior Jesus Christ,” 1594).11 Other through-composed historiae are those by Joachim a Burck (1568),12 Johann Steurlin (1576), Johann Machold (1593), Johannes Herold (1594),13 and Christoph Demantius (1631).14

Historiae that mix the characteristics of the responsorial and through-composed types are those in which the part of the Evangelist is performed by a soloist to a recitation tone, in the manner of the responsorial historia, but the parts of individual personages are set polyphonically, as are those of the through-composed historia. The earliest-known Lutheran historiae of the mixed type are those by Antonio Scandello (1517–80), a musician at the Dresden court beginning in 1549 and one of Schütz’s predecessors there as Kapellmeister (1568–80). A similar plan is adopted in both of Scandello’s historiae, the St. John Passion (1561 or earlier) and the Easter historia, the latter entitled Osterliche freude der siegreichen und triumphierenden Auferstehung unsers Herren und Heilandes Jesu Christi (“Easter Joy of the Victorious and Triumphant Resurrection of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ,” 1561? 1568? 1573?).15 In both works the lines of Jesus are always set a 4, the other individual personages a 2 or a 3, and the turbae a 5. The text of Scandello’s Easter historia, “harmonized” from the four Gospels and including an exordium and a conclusio, was set again by Rosthius in 1598 (his responsorial historia mentioned above) and by Schütz in 1623. Other noteworthy historiae of the mixed type are two closely related works by Rogier Michael (ca. 1554–1619) on the conception and birth of Jesus: Die Empfängnis unsers Herren Jesu Christi and Die Geburt unsers Herren Jesu Christi, both of 1602.16 Schütz would certainly have known Michael’s works, for the latter was a musician at the Dresden court beginning in 1574 and was Schütz’s immediate predecessor there as Kapellmeister (1587–1617). A work unusual for its subject matter is Elias Gerlach’s historia of the mixed type on the life of John the Baptist, Historia von dem christlichen Lauf und seligen Ende Johannes des Täufers (“Story of the Christian Vocation and Blessed End of John the Baptist,” 1612).17

The Historiae of Schütz18

Among the most important composers of the Baroque era, Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672) is significant in the history of the German oratorio for his introduction of the stylistic elements of Italian dramatic music into the German historia, which brought that genre to the threshold of oratorio. As a young man Schütz left his native Saxony to study in Venice from 1609 to 1612 with Giovanni Gabrieli. From 1617 until the end of his life, he was Kapellmeister for the Elector of Saxony at Dresden. He was absent from the Dresden court in 1628, when he traveled to Monteverdi’s Venice to familiarize himself with the most recent developments in Italian music. He was also absent when he served as the director of music at the court in Copenhagen for several years during the disturbed times of the Thirty Years’ War. Of Schütz’s five works that he called historiae, two are settings of the Easter and Christmas stories and three are Passions. Schütz’s historiae bear various relationships to the German oratorio, and two of them, those for Easter and Christmas, have often been loosely termed oratorios in musicological literature. Schütz’s Seven Words of Christ, called neither a historia nor an oratorio by the composer but occasionally termed an oratorio today, is also treated below.

FIGURE I-2. Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672), at 85 years of age. An oil miniature by an anonymous painter, 1670. (Reproduced by permission of the Bärenreiter Bild-Archiv, Kassel.)

The Easter Historia19

Schütz’s Historia der fröhlichen und siegreichen Aufferstehung unsers einigen Erlösers und Seligmachers Jesu Christi (“Story of the Joyful and Victorious Resurrection of Our One Redeemer and Savior Jesus Christ,” Dresden, 1623) is his earliest work in this genre. According to its title page, it was “to be used for spiritual, Christian edification in princely chapels...