![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Postoccupation Dilemma

Ideology and Contention in the Vincent Years, 1934-1941

Since a little over half a century, the country has

been the victim of the same practices of small, clannish,

ambitious leaders, who . . . do not understand the real

Haitian problem. Foreign intervention could not alleviate

this situation. Now the country should live under new laws.

—Manifeste de la Réaction Démocratique, 1934

Haiti faced a series of new challenges with the end of the U.S. occupation. Compared with the tumult of the years preceding 1915, the 1930s was a decade of relative political stability despite the absence of major political or economic reforms. Equally important were the strengthening of a semi-professional Haitian army, the Garde d’Haïti, the creation of vocational schools, and the affirmation of Port-au-Prince as the center of political power. President Vincent committed himself publicly to a new era of reformism akin to Roosevelt’s New Deal, and sought to deepen ties with the United States and Haiti’s powerful eastern neighbor, the Dominican Republic. There were, however, few changes in the economic and social structures. The elites continued to dominate the financial sector, and by virtue of this power were able to indirectly control the government. After 1934, the United States became Haiti’s leading trading partner, importing more than half of its annual coffee yield and carefully maintained influence of Haitian finance.

These developments favored the interests of urban elites and offered little benefits for the peasantry or urban workers. When the marines left, Vincent fast assumed a more authoritarian leadership style, especially after his reelection in 1936. Having cut his teeth as a fierce opponent of the occupation, the president was considered by mid-decade “one of the staunchest pro-Americans in the hemisphere.”1 He used the Garde d’Haïti to effectively silence his opposition with threat and imprisonment. Against this backdrop the political consciousness of the Haitian nationalists of the twenties assumed more radical forms.

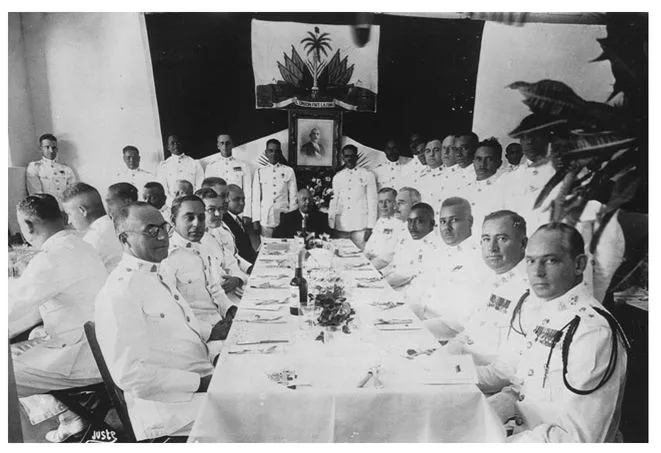

President Sténio Vincent (at the head of the table), Foreign Minister Élie Lescot (seated at Vincent’s right), and members of the Garde d’Haïti High Command celebrate Haitian Independence Day, 1 January 1934. Courtesy of U.S. National Archives, USMC Records.

This chapter explores the ideological and sociopolitical context of the radical movements of the thirties, their internal debates, the challenges they posed to the state, and the international environment that shaped interwar radicalism.

Color Is Nothing, Class Is Everything: The Marxist Vision of Haiti

The dismantling of marine control coincided with the fragmentation of the nationalist movement in the early thirties. The widespread repercussions of the Damien revolt provided enormous inspiration for the generation that came of age during the occupation. If the fervor created by the protest against the occupation in 1929-30 was to bear lasting fruit, a drastic restructuring of Haitian society was considered essential. While many of the nationalists of the late twenties acquiesced in their newfound political positions under Vincent, the more radical among them began to explore other political alternatives. In the 1930s the global appeal of Marxism among young radicals found resonance in Haiti.

Though Marxism had attracted the attention of some of the collaborators of La Revue Indigène, it never commanded any organized following. Nevertheless, this early interest was not lost on the country’s occupiers who, still reeling from the rise in black militancy and the Red Scare in the United States, deemed the social divisions in Haiti a suitable condition for Bolshevik influence.2 Widespread communist infiltration, in fact, had been cited by the U.S. Commandant of the Garde d’Haïti, R. P. Williams, as a principal cause of the Damien strike in 1929. In a somewhat paranoid report on the student strike submitted to the American High commissioner, Williams explained that “the recently formed young mens’ organizations which are in full control of the radicals . . . are working up interest among the school children in their demands for legislative elections and early withdrawal.” He added, “At Cape Haitian it is reported that children no longer salute the national colors at morning ceremonies, and are openly disrespectful to their teachers. At Jacmel . . . in the school children parade, the only colors carried was [sic] one flag of red with a green serpent.”3

Such claims were doubtless exaggerated and reflective of U.S. hysteria and the marines misunderstanding of nationalism and anti-occupationism. However, it also suggested that Marxist ideas were starting to capture the sympathy of several outstanding Haitian intellectuals who participated in the strike. This was a concern for the dominant forces in Haiti.

By 1931 Jacques Roumain, the most radical of the militants of the twenties, had detached himself from the nationalist movement. From the late twenties his writings, especially those in Le Petit Impartial written under the pseudonym Ibrahim, began to stress class-related problems as the most central issues in local politics.4 This was unsurprising given his background. Jacques Roumain was born on 4 June 1907 in Port-au-Prince to a well-respected family. On both sides, Roumain had connections with prominent Haitian statesmen, including his maternal grandfather, Tancrède Auguste, who briefly served as president (1912-13).5 Roumain attended the best schools in Haiti before traveling to Switzerland and Spain, where he studied agronomy.

On his return to Haiti in 1927, the young Roumain developed a reputation not only for his talents as a writer and poet, but also for his activism and commitment to social justice.6 For Roumain the early thirties were a period of intense personal transformation. He was inspired by the triumph and progress of the Bolshevik Revolution and envisioned similar achievements in his homeland. He saw firsthand the potential of popular protest to effect political change in 1930, something that the indigenous movement for all its cultural nationalism could not accomplish. Already an aggressive opponent of bourgeois standards, religious traditions, and imperialism, Roumain argued that, since the nationalist movement was born in the suffering of the majority, a political philosophy that sought to liberate them was the only acceptable model for Haiti. He gave an indication of this political awakening in a letter written to French writer Tristan Rémy in early 1932. “I have revised completely my political conceptions. . . . I am a Communist. At the moment I am not militant because the cadres for a political struggle do not yet exist in Haiti. The son of owners of extensive land holdings, I have renounced my bourgeois origins.”7

For the next few years Jacques Roumain, one of the country’s most gifted writers, would almost completely abandon his literary writings to devote his life to communist mobilization. He found support with two other radicals in their early twenties closely associated with the indigenous movement: Christian Beaulieu and the influential Louis Diaquoi, who briefly flirted with communism.8 Beaulieu and Roumain, intent on forming a communist party in Haiti, traveled to New York in the spring of 1932 with the hope of obtaining financial aid from the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA).9 With the promise of support, contingent on the formation of an underground party, the two returned to Haiti, where they began to meet with students and organize clandestinely in the popular areas of La Saline and Bel-Air.10

It is not known exactly how many participants supported the movement or attended the meetings. The scant evidence on the early mobilization activities of the communists suggests that the following was very small and strongest among more privileged students primarily drawn to Marxist ideas out of curiosity. This is understandable given the socioeconomic conditions in Haiti in the thirties. Labor unionism was still gestating and the global effects of the Great Depression made many urban workers grateful for employment and less willing to organize. Moreover, Vincent’s rhetoric of liberation was strong competition for Marxist radicals.

Whatever the real strength of communism in 1932, there was an undeniable worry among the elite of its potential growth. Once in power Vincent, fearing that the spread of radical ideas posed a potential challenge to his regime’s nationalist allure, commented in private that when the “Americans have gone the government will . . . have to rely on force to maintain itself in power.”11 Vincent made good on this promise, placing the country in a state of siege shortly after taking office and instituting martial law at various points throughout his rule. His trusted minister of the interior, Élie Lescot (1930-34), was a vigilant combatant of communism, expelling various foreign nationals suspected of being linked to regional movements.

The rationale for such drastic measures may be explained by the political nature of the battle between communism and nationalism in Latin America in the thirties. Across the region, communists were perceived as anarchists, the antithesis of what nationalism stood for. In most cases forceful repression was officially endorsed as a deterrent. Vincent justified this approach once he learned of the connections between Haitian Marxists and agents of the CPUSA. In late 1932 correspondence between Roumain and communists in New York was intercepted by Haitian authorities and taken as evidence of an attempt to organize an active movement in the country. The government charged that Roumain and his associates were planning a general strike for the second week of January intended to hasten U.S. withdrawal and overthrow the regime. The funding for this grand scheme, they maintained, was provided by the New York chapter of the CPUSA and orchestrated by a Cuban communist living in Haiti, Dr. Omar Lind. At the same time the supposed plot was unearthed, the Haitian minister in Paris reported that Haitian radicals in the Latin Quarter were circulating news of active communist cells organizing in Haiti.12

Implicated in the Haitian red scare of the early thirties was another veteran of the indigenous movement, Max Hudicourt. Hudicourt was born on 25 June 1907 to a light-skinned elite family in the southern province of Jérémie. He moved to Port-au-Prince at a young age and became politically involved during the 1920s. Hudicourt, like Roumain, regarded Marxism a political ideology applicable to the Haitian situation. For him, Vincent’s policies were antidemocratic and the president had betrayed the nationalist movement by being far too compliant with the United States. In contrast to his communist peers, however, Hudicourt was less fervent in his devotion to Marxism. Still, his background as a prominent member of the intelligentsia, his remarkable oratorical skills, and his connections with radicals in the city and the southern provinces, as well as outside Haiti, made him an influential figure.

Hudicourt was the leader of the radical organization La Réaction Démocratique (RD), formed in 1932, that included leaders of the student strike such as J. D. Sam, Georges Rigaud, and Jean Brierre. The group expressed their protest in the antigovernment paper Hudicourt edited, Le Centre, which featured open admiration for state control of the means of production. Though communist language was intentionally avoided, he was accused of disseminating communist ideas. As with the Roumain case, letters between Hudicourt and a known communist in New York were found and used as evidence of his participation in a plot to overthrow the government.13

Max Hudicourt

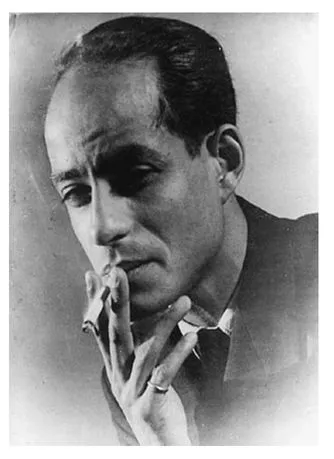

Jacques Roumain

Based on these spurious claims, the two leading figures of the Haitian Left, Hudicourt and Roumain, were arrested, tried, and imprisoned for three months at the beginning of 1933.14 Foreigners linked with both men, including Lind and H. Peguerro, a Dominican radical accused of attempting to stir up a strike of workers at the Haitian American Sugar Company (HASCO), were deported. The marines, anxious to rid the country of Marxist influ-ences before leaving, launched a widespread campaign for the “Suppression of Bolshevist Activities” in Haiti, which they argued were “being organized and spread among the working class.”15 The sentencing of these high-profile leftists attracted much coverage in the local and international press and provoked criticism from labor organizations in New York, which lobbied for their release.16

It also exposed crucial differences in the political approach of both men that would bear significantly on the future of Haitian Marxism. After the trial, Hudicourt categorically declared, “I am not a communist. I believe in the fundamental principles of the doctrine but find it too ideological for our national well-being.”17 Roumain, for his part, defiantly held firm to his communist position as a statement written from his cell in the National Penitentiary attests: “My devotion is to the workers and to find a scientific solution of the Haitian problem . . . and not even the name Lescot or the mulâtre bourgeois leaders of exploitation and accomplices of American imperialism can ever discourage me.”18

The attention from abroad, coupled with a hunger strike Roumain and Hudicourt began in early February, led to the release of both...