![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Cultural Meaning of Nationalism

Nationalism became one of the most influential political and cultural forces in the modern world because it gives people deep emotional attachments to large human communities and provides powerful stories to explain the meaning of public and personal lives. Modern people encounter stories about their nations in almost every sphere of their political, social, and economic activities—from election campaigns and tax payments to professional training, military service, and family relationships. Children learn their nationality almost as soon as they learn to talk, and virtually everyone refers to national cultures when they describe personal or group identities: “He is French, she is Russian, they are Japanese, we are Egyptians, I am American,” and so on through every part of the world. Nationalism expresses the deep and apparently universal human desire to participate in and identify with social communities, but these identities have only acquired their distinctive nationalist meanings over the last two or three centuries. The history of nationalism thus leads everywhere to the history of modern politics, cultures, and personal identities.

Three stories from the early history of modern nations can introduce us to the cultural influence of nationalism. In September 1776 a twenty-one-year-old man named Nathan Hale was executed by the British army in New York on charges of spying for America’s new Continental army. Hale therefore became an early symbol of national sacrifice in the new American nationalism that was emerging in a war for political independence from Britain, and his famous last words—“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country”—became a moral lesson for every subsequent American generation.

In April 1792 a soldier in the French army named Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle sat down near the Rhine River in Strasbourg to write a song about France’s just-declared war with Prussia and Austria. Rouget de Lisle completed the song in a day, but its revolutionary call to arms became a permanent expression of French nationalism. “La Marseillaise” (as the song was soon called) resembles Hale’s last words in stressing the virtues of sacrifice, and it describes the nation’s cause as the highest duty for every citizen:

Let us go, children of the Fatherland

Our day of glory has arrived.

Against us stands tyranny

The bloody flag is raised;

the bloody flag is raised.

In the winter of 1807–8, the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte delivered a series of popular “Addresses to the German Nation” to large audiences in Berlin. Speaking shortly after the French army had taken control of the city, Fichte predicted that a new Germany would arise from this national humiliation. He conceded that the French dominated Europe in 1807, but he offered his audiences the philosophical assurance that decisive German actions would create a different future in which “you will see the German name exalted . . . to the most illustrious among all the peoples, you will see in this nation the regenerator and restorer of the world.”1

The American spy, French soldier-songwriter, and German philosopher lived in different places, spoke different languages, and advocated different national causes, yet they all contributed the words and exemplary actions for new nationalisms. Representing three social roles that every nationalism requires (martyr, lyricist, prophet), each man stressed the danger of enemies, the need for sacrifice, and the national ideal as an essential component of human identity. Their stories were connected with the revolutions and wars that first produced and expressed the modern ideas of nations and nationalism, and their lives point to the overlapping personal and public identities that have made nationalism so pervasive and powerful in modern world history. More generally, the actions and cultural memories of Hale, Rouget de Lisle, and Fichte exemplify the cultural construction of nationalism—the ubiquitous historical process that is the subject of this book. Nationalism has evolved in very different places, political systems, and historical contexts, but all nationalists assume that each person’s life is inextricably connected to the history, culture, land, language, and traditions that (theoretically) form a coherent national society and state.

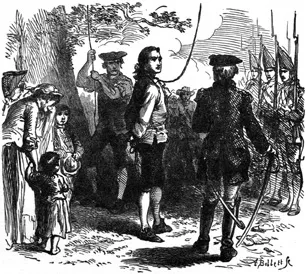

Unknown artist, The Execution of Captain Hale, photo engraving. The weeping woman and the two children suggest how Nathan Hale’s death was portrayed in history books as an exemplary sacrifice for the American nation and a patriotic model for later generations. (In Benson J. Lossing’s popular illustrated book, Lossing’s History of the United States 3:887 [New York, 1909])

Nationalism and Modernity

Although nationalist movements frequently claim to represent long-existing cultural or ethnic groups, most historians argue that modern nationalist ideas and political campaigns did not develop before the late eighteenth century. This historical argument therefore challenges the typical nationalist’s belief in the very old or even primordial existence of national identities. In contrast to the nationalists’ emphasis on an enduring national spirit or essence that reappears constantly in the nation’s history, most historians stress the influential cultural work of intellectuals and political activists who created the modern stories of national heroes, popular folklore, and shared traditions. To be sure, this historical approach to nationalism recognizes that people have always shared collective identities in their towns, families, religions, and geographical regions, but the nationalisms that spread in modern texts and state institutions promoted new personal identifications with much larger territories and more diverse populations.

Despite their general agreement on the historical influence and modernity of nationalist politics and ideas, historians frequently disagree about the premodern origins of national communities and identities. The resurgence of nationalist and ethnic violence in the 1990s contributed to new historical interest in the earliest emergence of nationalist thought, which some writers have traced back to ancient Israel or other ancient Mediterranean cultures.2 Most historians, however, continue to describe nationalism as a distinctive form of modern thought and political culture. They assume that nationalism has grown out of and shaped specific social and political systems in modern cultures and has no essential origin in ancient or premodern societies. As the historian Hans Kohn noted in a classic study of the “idea” of nationalism, it “is first and foremost a state of mind, an act of consciousness,” which is constructed like other ideas through constantly evolving historical conflicts, social relations, and political movements.3 A more recent historian of nationalism, Liah Greenfeld, argues that nationalism is not simply the outcome of modernizing social and political institutions (for example, capitalism and nation-states); it is instead a key source of modernity. “Historically,” Greenfeld explains, “the emergence of nationalism predated the development of every significant component of modernization.” Although other historians differ from Greenfeld by exploring the constant interplay of modern and premodern ideas or by inverting her account to argue that modern social institutions actually produced nationalist ideologies, the linkage between nationalism and modernity has become a widely accepted truism of historical explanation.4

My own account of nationalism draws on recent historical and theoretical perspectives to argue that national identities are historically constructed and began to develop their modern forms in late eighteenth-century Europe and America. In contrast to many histories of Western nationalism, the following chapters show how the themes of European nationalism appeared also in the nationalism of the emerging United States, where the construction of a new national identity against an imperial European power can be compared to subsequent nationalisms in other regions of the world. Nationalism has always developed overlapping political and cultural ideas, all of which share the central assumption that the well-being and identity of individuals depend on their participation in a national culture. This assumption shapes the cultural claims of nationalism and provides a starting point for the historical analysis of nationalist thought. If social groups and individuals define their identities with the language of national cultures, then the historical construction of those cultures becomes crucial for understanding a whole range of historical issues—from politics and public conflicts to the interpretation of family life, gender roles, education, and death.

The intersection of collective and personal identities suggests why the cultural history of nationalism (the influence of language, history, religion, literature, and public symbols) goes beyond what social or military or economic history can explain about the emergence of nationalist institutions. Nationalism develops in the convergence of modern political and cultural narratives that construct the shared history of people living in a specific geographical space; these narratives then typically claim a fundamental human right for such populations to have an independent, sovereign state. National narratives also affirm unique, collective identities by stressing that each national population differs from the people and cultures in all other nations. Nationalism is therefore a more coherent system of beliefs than patriotism, which, in my view, expresses emotional identifications with particular places, communities, or governments but lacks the self-conscious cultural themes of nationalist movements and institutions. My interest in the cultural construction of nationalism, however, does not ignore or negate other explanations for the popularity and power of modern nationalisms; in fact, the cultural approach to the multiple layers and political power of nationalism should also recognize the insights of alternative interpretations, including the ethnic and economic themes of recent social theorists.

I noted earlier that the violence of contemporary ethnic conflicts has prompted some analysts to question the modernity of nationalisms and examine the premodern origins of modern national identities. The English sociologist Anthony D. Smith, for example, complains that contemporary fascination with the “cultural invention” of nations leads too many historians to ignore the ways in which national identities depend on long-developing “patterns of values, symbols, memories, myths, and traditions that form the distinctive heritage of the nation.” This “distinctive heritage” limits what intellectuals or politicians can actually claim for the cultural traditions of a nation, and cultural elites can never simply construct a new national culture. The modern language of nationalism must refer to realities or remembered experiences outside of writing, Smith argues, and these realities are evoked in the “common myths and memories” of ethnic groups and national populations who claim to “constitute an actual or potential ‘nation.’”5

Smith therefore assumes that nationalism has deep roots, because the people in each specific ethnic or national community learn the stories of a shared past that are “handed down from generation to generation in the form of subjective ‘ethnohistory,’ [which] sets limits to current aspirations and perceptions.” Smith assumes that this “ethnohistory” or “ethnosymbolic” memory sets the parameters of national cultures and forces the would-be creators of a national identity to reconstruct the “traditions, customs and institutions of the ethnic community or communities which form the basis of the nation.”6 The concept of ethnic identity for Smith and others who build on his theories refers to cultural traditions and a shared history rather than to specific racial or biological traits. As Walker Connor explains in a somewhat different analysis of “ethnonationalism,” the “nation connotes a group of people who believe they are ancestrally related,” though Connor insists that this “sense of unique descent . . . need not, and in nearly all cases will not, accord with factual history.” It is the belief in a common “descent,” however, that shapes nationalism and elicits emotional attachments to what the historian Steven Grosby calls a “community of kinship” among those who describe themselves as a nation.7 Although the ethnohistorians tend to lose sight of how national languages, symbols, and memories constantly (and rapidly) evolve through new systems of communication, their insistence on the premodern origins of the belief in a shared ancestry offers important critical alternatives to the recent emphasis on the modern cultural construction of nationalisms.8

Another influential alternative to recent cultural histories of nationalism appears in the work of Ernest Gellner, who, unlike the ethnohistorians, argues that nationalism emerged as an ideological response to the far-reaching economic changes that spread across the Western world in the nineteenth century. Describing nationalism as a practical solution to the needs of industrializing modern societies, Gellner explains that new, complex economies required specialized divisions of labor, educated workers who could communicate across long distances, and mobile populations that could read the same language and follow the same laws. Nationalism thus provided the rationale and institutions for this educated, mobile workforce through the creation of the standardized languages, schools, and technical training that separated industrialized nations from traditional agrarian cultures. This pattern would reappear often in modernizing societies around the world. “The roots of nationalism in the distinctive structural requirements of industrial society are very deep indeed,” Gellner argues, and nationalism develops whenever the social structures of a culture begin to evolve away from the relatively stable, hierarchical relations of peasant communities. “It is not the case . . . that nationalism imposes homogeneity; it is rather that a homogeneity imposed by objective, inescapable imperative eventually appears on the surface in the form of nationalism.”9

Gellner’s economic structuralism carries a valuable reminder that politics and culture always remain connected with economic life, yet his economic explanations fail to account for the complexity of national cultures or the emotional passions that such cultures regularly generate. The cultural meanings of nationalism go beyond economic modernization into nuances of language, history, and religion that have little or no value for standardized labor forces, though they create emotionally charged identities for which people are willing to kill and die. Indeed, Smith’s search for continuities with premodern ethnic, cultural traditions may tell us more about the powerful emotional attraction of nationalism than we can learn from Gellner’s account of economic modernization. But if neither premodern ethnic communities nor modernizing economic systems can adequately account for the political power and emotional meanings of modern national cultures, how do political nationalisms and national cultures come together in the overlapping personal and public spheres of individual lives?

Cultures and Identities

People always have multiple identities. They describe themselves (and are described by others) through references to their families, work and professional status, wealth, gender and race, education, religious affiliations, and political allegiances—not to mention their other identities such as loyalties to sports teams, club memberships, or hometowns. All of these identities depend on social relations and interactions with other people, and many have been integral to human experience since the beginning of civilization. Nationalism does not usually deny or displace other forms of personal identity, but it typically defines national identity as an essential identity that gives coherence to all other aspects of a person’s life. The ascribed traits of nationality are used to define virtually every level of public and private life, so that we hear about “Italian” families, “German” workers, “American” Protestants, “Chinese” food, “English” gardens, or maybe a “French” kiss.

Nations are thus pervasive cultural categories that structure, regulate, and contribute meanings to most of the actions and relationships through which we understand our lives. Loyalty to the nation “flourishes,” as the historian David Potter has explained, “not by challenging and overpowering all other loyalties, but by subsuming them all and keeping them in a reciprocally supportive relationship to one another.”10 This implicit nationalism in the relationships of everyday life becomes more explicit and coercive during wars, when national governments demand the lives of young people and the labor, wealth, or disciplined loyalty of entire societies. Nationalism provides the justification for the most wide-ranging military and political mobilizations of modern populations, but it can also be found, notes Peter Alter, “whenever individuals feel they belong primarily to the nation, and whenever affective attachment and loyalty to that nation override all other attachments and loyalties.”11 Indeed, nationalists believe that even the most private human activities and attachments acquire wider significance through their connections with a nation: “family values” and “religious morality,” for example, may be celebrated as essential to the survival of a strong national culture, whereas a declining commitment to marriage or religion may be interpreted as the cause of national weakness and decline.

Modern nationalism provides more than reinforcement of traditional families or religions, however, because it can also compensate for the breakdown of traditional social, cultural, and religious hierarchies and attachments. Identifying with the power of a nation may become a consolation or replacement for losses and disappointments that accompany the growth of modern cities and economic institutions. Liah Greenfeld, for example, argues that a social and cultural “identity crisis” has preceded the embrace of nationalism in almost every modern society. Set free from the hierarchies and social categories of traditional cultures, individuals and groups in modernizing societies have regularly experienced what Greenfeld calls a sense of social “anomie” and disorientation. Fervent nationalists often emerge in such contexts, transforming deep resentments about the lack of recognition for their work, social status, or social group into passionate claims for national achievement and superiority. The most intense nationalist i...