This is a test

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

At the time of his death, Ulysses S. Grant was the most famous person in America, considered by most citizens to be equal in stature to George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. Yet today his monuments are rarely visited, his military reputation is overshadowed by that of Robert E. Lee, and his presidency is permanently mired at the bottom of historical rankings. In U. S. Grant, Joan Waugh investigates Grant's place in public memory and the reasons behind the rise and fall of his renown, while simultaneously underscoring the fluctuating memory of the Civil War itself.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access U. S. Grant by Joan Waugh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías militares. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Biografías militaresChapter One

Youth

U. S. Grant sprang from humble, commonplace origins on the Ohio frontier. Huge statues and monuments in eastern and midwestern cities and scattered national military parks in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Virginia, most famously memorialize him, but serious students of the man should visit the obscure Ohio hamlets where he was born, reared, and educated in modest circumstances. The intrepid tourist visiting Point Pleasant can view Grant’s birthplace, a twenty-feet-square wood structure. After his death, the house went “on tour” throughout the country before returning to its original location. Grant’s boyhood home in Georgetown is also preserved, as is his father’s tannery, and the two schoolhouses he attended.1 Grant’s memoirs highlight with pride his plain western “ordinariness,” a trait that cemented a bond between himself and so many soldiers and citizens during his long public life. Countless contemporaries noted this characteristic of ordinariness, expressing it differently. A Herman Melville poem described Grant as “a quiet Man, and plain in garb,” while Walt Whitman’s Grant was “nothing heroic … and yet the greatest hero,” and Mark Twain summed him up as “the simple soldier.” For Union officer Theodore Lyman, the essential Grant “is the concentration of all that is American.”2

The above descriptions flattered the Union hero, but they also contained a hard kernel of truth. Here, reality mirrored well-publicized myths spread by the earliest biographies but also vetted by later scholars.3 Grant’s family story echoed the experiences of a majority of his countrymen and -women who, like himself, grew up in rural small towns or on farms in the early national period of the nineteenth century. His experiences soon diverged from that majority when he left the Buckeye State and entered the United States Military Academy in New York in 1839. From that time, Grant gained an elite national perspective framed by his military education at West Point and his coming of age as a soldier in the Mexican War. Along the way, the shy youth from Ohio acquired strengths and developed talents that overcame his weaknesses of character and life challenges, setting the stage for his accomplishments. Grant’s early failures perplexed many, and some prefer to ignore or disparage his first forty years, adding mystery to his myth. T. Harry Williams began an essay, “Grant’s life is, in some ways, the most remarkable one in American history. There is no other like it.” Williams added next, “His career, before the war is a complete failure.”4 Always, Grant retained his commonplace demeanor, puzzling even his closest friends who sought to understand his particular great genius. His great friend and comrade William T. Sherman said, “Grant’s whole character was a mystery, even to himself.”5 Historian Bruce Catton remarked, “He looked so much like a completely ordinary man, and what he did was so definitely out of the ordinary, that it seemed that as if he must have profound depths that were never visible from the surface.”6 Is Grant really so much of a mystery? Surely, a glimmer of the “depths” of Grant’s personality can be discerned through an examination of his youthful influences and, just as surely, provide the key to his later fame.

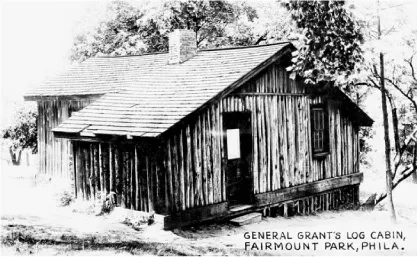

One of Grant’s humble abodes on public display (author’s collection)

Origins

Grant stated, “My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral.”7 Matthew Grant, his earliest ancestor, came to Massachusetts in 1630; direct descendants went to Connecticut, then to Pennsylvania, and his immediate forebears ended up in the Western Reserve. The ability and desire to pack up and move somewhere else when failure struck or ambition beckoned was part and parcel of what ordinary white Americans considered their right. So too was the expectation and hope that one of those moves would result in an improvement from their previous lives. Many failed; but many succeeded. Character traits such as self-reliance, self-control, and thriftiness became associated with doing well in the country’s burgeoning commercial economy. It was a time that afforded opportunities for poor, propertyless men to improve their condition. Jesse Root Grant was a shining example of such men.8

In the year of his son’s birth, 1822, Jesse was already known as an ambitious and hard-working young man on the rough-hewn Ohio frontier. His own father, Noah, a captain in the Revolutionary War, was neither ambitious nor hard working. Instead he had a reputation for drifting and drinking. Noah left Connecticut, tried his luck in Pennsylvania, and ended up in 1799 living in Deerfield, Ohio, with his second wife, Rachel, and their seven children. Rachel’s sudden death in 1805 broke up the family and eleven-year-old Jesse was alone in the world. Local families hired him to do chores and provided him with room and board. Then, Judge George Tod of the Ohio Supreme Court and his wife took pity on the loquacious teenager and included him in their family circle. From the Tods, a grateful Jesse received security, warmth, and encouragement for his future. By sixteen, Jesse had determined that the fastest route to independence was to master a trade. He chose wisely. He would be a tanner, someone who made leather from rawhides. A good living could be gained selling leather, providing a growing population with shoes and saddles and other desirable products.

Like most young men at the time, Jesse started at the bottom of his profession, first toiling in a local concern and then working as an apprentice at the tanning factory of his older half-brother, Peter, across the Ohio River, in Maysfield, Kentucky. Jesse was reunited with family members (Peter and his wife had taken in Noah and the two youngest Grant children) for the five years of his apprenticeship. Jesse had earlier received six months of schooling, “but his thirst for education was intense.”9 He loved to read, seizing the opportunity to do so in the evenings, after a hard day of labor. At twenty-one, he attained his full height of nearly six feet and was ready to go out on his own.

Slave-state Kentucky did not suit him, and he returned to Deerfield, and Ohio. His first real job was working in Owen Brown’s tannery. He lived with the Browns, who reputedly operated a station on the Underground Railroad. They had a son named John, later the abolitionist comet whose 1850s bloody rampages in Kansas and at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, helped to start the Civil War. According to U. S. Grant, Jesse often ruminated about John Brown in later years. “Brown was a boy when they lived in the same house,” his son wrote, “but he knew him afterwards, and regarded him as a man of great purity of character … but a fanatic and extremist in whatever he advocated.”10 Jesse’s carefully accumulated savings were wiped out when he fell seriously ill from malaria. Fully recovered a year later, he started over in Point Pleasant, in Clermont County, Ohio, and soon impressed the small community with his steady industry. Anxious to start a family, Jesse courted a young woman whom he wanted to marry in the nearby town of Bantam. Hannah Simpson was from a prosperous farming family with recent roots in Pennsylvania. Her parents, John and Sarah Simpson, had moved to Clermont County in 1819 with their four children. Quiet and plain, the twenty-three-year-old Hannah attracted her prospective suitor, who described her as an “unpretending country girl, handsome but not vain.”11 John and Sarah believed that twenty-seven-year-old Jesse would make a fine husband and a good provider. Although he was still an employee, he planned to own his own factory within a few years. Hannah and Jesse received her parents’ consent, and they were married in June of 1821.

Georgetown Days

Their first child was born on April 27, 1822, in a tiny rented two-room house high on a bluff above the Ohio River, beside the tannery where Jesse worked in Point Pleasant. The baby’s rather odd name, Hiram Ulysses, was the result of a compromise forged between mother-in-law Sarah Simpson and Jesse (who both favored Ulysses, after the Greek military hero of mythic status) and Hannah and the rest of her family. Soon enough, Hiram was dropped and the little boy commonly called “Ulysses” (sometimes shortened to “Lyss”). Grant’s own preference may have been for his original birth name. His schoolbooks revealed that he wrote “Hiram U. Grant” on the front pages.12

Jesse sought a livelier commercial venue and moved his family a short distance east to Georgetown, Ohio. Georgetown was a small village set back about ten miles from the river in Brown County. The village was surrounded by forests of oak, walnut, and maple trees and flanked on two sides by large creeks. The outer land was settled by farmers who grew corn and potatoes in the rich earth. To a large extent, both the farmers and townspeople came from the southern states of Kentucky and Virginia, distinguishing the Grants as proud “Yankees.” Quickly, Jesse bought land, established his own tannery business, and built a modest but pretty two-story brick house. Over the years, the Grants had five more children: Samuel Simpson (1825), Clara Rachel (1828), Virginia Paine (1832), Orvil Lynch (1835), and Mary Frances (1839). The succession of babies guaranteed that Hannah would not have too much time to spend with Lyss. As a result, he enjoyed an unusual independence while growing up. “I had as many privileges as any boy in the village, and probably more than most of them,” Grant recalled.13

Years afterward, reporters asked townspeople to assess Hannah’s influence on her famous son. One observer commented: “Ulysses got his reticence, his patience, his equable temper, from his mother,” while another put it more simply: “He got his sense from his mother.”14 A spare, undemonstrative, religious woman, Hannah rarely engaged in superfluous conversation. She preferred to stay within the confines of her domestic responsibilities, and there is no doubt that she took her maternal duties seriously. People noted that Ulysses was always clean and neatly dressed; the girls seemed to like him. He was described as nice and polite, and a good listener. Unlike many of his friends, he reputedly never swore. “He was more like a grown person than a boy,” remarked a classmate.15 Clearly, Ulysses imbibed well the values taught by Hannah. He admired her spirituality, although he declined to share it. She was pious, but not an “enthusiast.” Ulysses was never baptized and felt no pressure to become a church member. His son, Jesse Root Grant, described his unchurched father as a “pure agnostic,” adding that “I never [heard] him use a pious expression.”16 Hannah did make sure that the family attended services every Sunday at the town’s Methodist church. In general, Ulysses’s parents were fairly easygoing with their children. Although demonstrable tensions existed, particularly between Jesse and Ulysses, later a grateful son paid tribute. “There was never any scolding or punishing by my parents,” he wrote, and there is much contemporary evidence confirming the accuracy of his statement.17

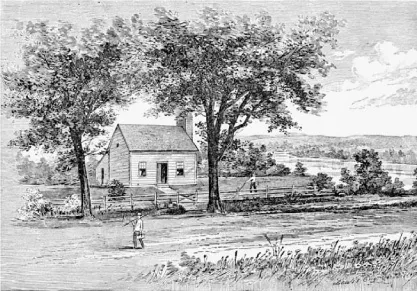

Grant’s birthplace in Point Pleasant, Ohio, as presented for young patriots. A large part of Grant’s appeal, as general and as president, rested on his “common” roots, portrayed in countless representations such as this one from a children’s book. (Elbridge S. Brooks, The True Story of U. S. Grant [Norwood, Mass.: Lothrop, 1897])

Jesse and Hannah prospered in Georgetown. The source of their prosperity was tanning, but Jesse added to his holdings by buying a farm. Children were expected to work, and Ulysses was no exception. He was a quick learner and eager helper, and at the tender age of five he already displayed the beginnings of his uncanny affinity with horses. By the time he was seven he was hauling wood for his father’s shops and at age eleven was strong enough to plough by himself. Ulysses grew up hating the sight and smell of his father’s factory, reeking of blood from slaughtered animals and the tannic acid used to cure the hides. One time, working beside Jesse, he said, “Father, this tanning is not the kind of work I like. I’ll work at it though if you wish me to, until I’m twenty-one; but you may depend upon it, I’ll never work a day at it after that.”18 He much preferred helping on the family’s farm. Ulysses recounted those days with pleasure, and he especially enjoyed any and all work that involved managing horses, “such as breaking up the land, furrowing, plowing corn and potatoes, bringing in the crops when harvested, hauling all the wood, besides tending two or three horses, a cow or two, and saving wood for stoves, etc., while still attending school.”19

Despite his family responsibilities, Ulysses was sent at age six to one town school and at age eight to another. Public education was not free, and day schools charged a modest “subscription” fee. Both parents valued education, particularly Jesse, who felt keenly his own lack in that area. He wanted his son to have all the advantages that had been denied to him. The Grant sitting room eventually boasted an impressive library of thirty volumes, and Jesse encouraged all his children to read often. At times a fidgety learner, Ulysses still remembered: “I never missed a quarter from school from the time I was old enough to attend till the time of leaving home.”20 One of his teachers assessed him as an average student but noted that his “standing in arithmetic was unusually good.” At age twelve...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- U. S. Grant

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Youth

- 2 The Magnanimous General

- 3 A Great Soldier Might Be a Baby Politician

- 4 Historian of the Union Cause

- 5 Pageantry of Woe

- 6 The Nation’s Greatest Hero Should Rest in the Nation’s Greatest City

- Epilogue Who’s [Really] Buried in Grant’s Tomb?

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index