![]()

Chapter One: 1925–1926: Idyllic Years

Thomas Wolfe first met Aline Bernstein aboard the Olympic in August 1925 on his return trip from Europe. Their love for one another was deep and almost instantaneous, and by October they had become constant companions. The following year and a half was near-perfect for the two lovers. It culminated with their trip to England, during which time, after Mrs. Bernstein’s departure for New York, he wrote the major part of the book that was to become Look Homeward, Angel. Yet the turbulence that lay ahead was foreshadowed in many of the letters that Wolfe wrote during this period. His bitter and unjustified accusations concerning Mrs. Bernstein’s fidelity were to become increasingly strident as the relationship continued.

1. [New York, Fall 1925]

My dear—

I came down but couldn’t get in—will you call me up at dinner time? The flowers are lovely. They were the only ones I got. I tried to get you on the telephone about 1:30 after I came up from meeting my sister1 but no answer.

My love, Aline

2. Westport, Conn.1 [December 1925]

My dear—

We are going home this afternoon, and I wonder if I will have some word from you. I have been going along on your telegram since you left. Did you ever get a place to sleep on the way home? If I had only had the time, I am sure that I could have made them put an extra car on for you.—It has been bitter cold ever since you went away, but clear and sunny. We have been out of doors all the time, skating or walking, and yesterday we motored up to New Haven to do a little light antiqueing. I have never given Lillian a wedding present, and we found some lovely old silver. This place is a dream[,] so beautiful and so comfortable. I am not much of a skater, but Edla2 is and she takes me around a good bit. I have been in my bed before ten every night, and then a nice quiet read.—I wish you could have been down for my stage debut.3 It was grand, you never in the world would have known me. I wore a black wig and a tight fitting long dress, and stood very straight and quiet like a lady. Mr. Baker4 was very enthusiastic about the production. I had a talk with him during the second intermission and all the time I wanted to speak of you but I didn’t. I wonder whether you are working on the other play.5 And have you had glorious meals at home? And have you been to lots of parties? At any rate, you have had a rest from your teaching and other worries and dissatisfaction. I have been thinking of you pretty constantly (most inelegant expression)[. . . . ]

3. [Asheville, North Carolina] Monday [December 1925]

This is the only paper handy at the moment—it must serve, for my desire to write you a word is stronger than my need to wait.1

Your letters and your cablegrams came:—they have been almost committed to memory—red Embers in them ashes of my heart and hope[.] I came home to a Christmas of death, doom, desolation, sadness, disease, and despair: my family is showing its customary and magnificent Russian genius for futility and tragedy.

A cousin of the Wolfe family died a few hours before my arrival;2 pneumonia—He was a good hearted, good natured and uninspired drunkard, was taken ill on a weekend spree, and lived four days. The infinite capacity of my people to pile it on strains belief. My brother3 met me at the station with the news that another member of my damned and stricken family had been lost; that he was troubled by his appendix, my mother by a severe bronchial cold which might develop into pneumonia, and that my sister,4 just returned from an interrupted rest cure at the hospital, had hysteria and had broken down under the nervous strain of Christmas preparation. He then wished me a merry Christmas.

Today my mother, thanks to good medical attention, and her own sturdiness, seems practically well; my brother is robust and damnably nervous, as usual, and my sister, able to talk coherently for the first time without tears, has been carted away to the hospital for a rest. She has exhausted herself by her own nervous generosity— which is a kind of obsession—by brooding over her failure to have children, and by frequent and stealthy potations of corn whiskey, a jug of which is always on tap in the cupboard. This last none of us will admit, and all of us know it is true. To finish it, under concerted amount of family funerals in the company of long faced relatives, listening to uneasing post mortems at home and abroad on the causes of my kinsman’s demise—how he was hale and well Sunday, what he had said, done, eaten, how old man Weaver or old lady Campbell or young Jack Rogers had been taken under similar circumstances (we are here today and gone tomorrow; its all for the best, he shappier-where he is; were all put here for a purpose; it was the Lord’s will; and various other philosophical profundities tending to prove that the demise of a toper from exposure and whiskey is really the result of beneficent machinations of Godalmighty); advice as to the people I should visit, the food I should eat, the times I should do it—I have blown up, moved to a hotel, and saturated the leaden waste that coats my soul with quantities of white raw burning devastating corn whiskey!

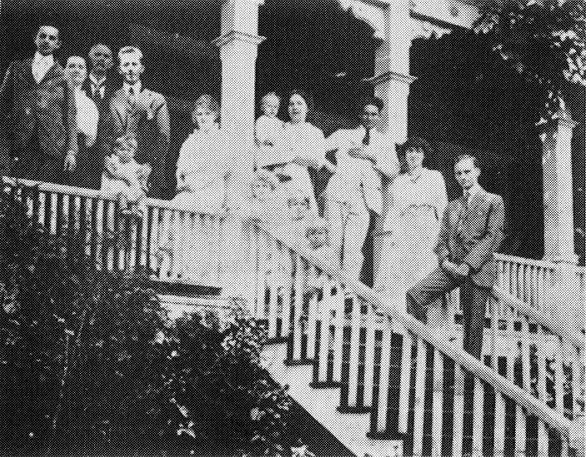

The Wolfe family, circa 1914. (In left group, left to right, standing) Thomas Wolfe; Julia Wolfe; W. C. Wolfe; Fred Gambrell (?), husband of Effie Wolfe; (seated) two Gambrell children (?). (In right group) Effie Wolfe Gambrell; Fred Wolfe; Mabel Wolfe; Ben Wolfe; and four Gambrell children (?) (From a copy in North Carolina Collection, UNC Library, Chapel Hill)

What the upshot will be I know not—whether I stay here a week, a month, a year, or the rest of my life. I have passed the greater part of my life very pleasantly in hell, and I may spend the remainder of it very pleasantly in a large, comfortable, convenient and well equipped mad house, which beckons to me invitingly forty miles down the mountain.

My people—my mother, sister, brother-in-law5—had planned to go to Florida this week6—that, apparently, is off. My own crown obsession at present is that I must go to Richmond—for I know not what—but go to Richmond I will, by God, if I have to walk, freeze, starve, beg and murder.

The weather is stabbing cold: the Janus-headed Perversity who rules my crazy destiny presented me with ordeal by ice the moment I came South. If I go North it will be to find the roses out.

If I wonder at what you have written concerning the purification of soul association with me has brought you[,] it is because of its implication to me: if you feel cleansed, it is purification by flame, torture, hell-fire—at your exceeding great cost. Whoever touches me is damned to burning. You are a good great beautiful person—as faithful here as this hot life has let you be—but eternally true and faithful to yourself and all others in the enchanted islands where, unknown to these phantoms, our real lives, our real ages tick out their beautiful logic.

The suggestion that I can do anything for you—that, miserable as I am, I have power to cleanse purify or judge such a person, almost dehumors me by its extravagance.

Write me when you can. Tom

The same address[.]

Sometime during the winter of 1925–26, Wolfe moved into the loft apartment at 13 East Eighth Street, which Mrs. Bernstein shared as a studio. They spent hours together here, recounting childhood memories and recreating scenes and personalities from the past. During the spring, Wolfe resolved to begin working upon an autobiographical novel. Aware that he could not begin so important a task under the present circumstances, Mrs. Bernstein offered to finance a trip to Europe as soon as his teaching duties were over. She would continue to support him so that he could give up his job at the university and work without interruption until he was ready to come home.

Late in May, Wolfe traveled to Boston. After briefly returning to New York, he continued on to New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia.

4. [New York] Neighborhood Playhouse/Monday [May 1926]

My dear—

The Grand St. Follies1 have to hold off a moment while I write to you. It was nice to get your letter and know where you are. You can’t imagine what a queer feeling it was to have you gone, and not sure where[.] I sent you a telegram and I trust you received it.—I also have had a little taste of spring, I went to see Lillian at Westport Saturday evening and came home Sunday at about 4 P.M.—Every thing was so lovely. We had a long walk Sunday morning early, I wanted to share every tree and flower with you. You will be back soon I know but it doesn’t seem likely, I cannot get used to not having you near. Your attitude toward the Boston leg2 is reassuring, but I do not like what you say about your being domesticated. Darling you must never be not wild, but naturally I like to be wild along with you.—I should like to go like lightning somewhere. Not to Boston though. I took your books back to the Library Saturday and tomorrow expect to go about the ticket. You cannot imagine how it is to work at 8th St without you. I looked at your blue suit3 so hard today I was convinced it would get up and walk around. But it didn’t, but it will some day soon, with someone inside it. Maybe though you will not wear it again, as you have two others now. I know you must be resting yourself, I only hope the naughty small instructor hasn’t crossed your path.—Please dear keep well and do some writing each day.—I long to see you and talk to you. We are almost snowed under with work but I am getting on famously and hope to have some time free for you when you come. I have been getting home to bed early, by 11:30 or 12. The night at Westport I turned in at 9:30, and really have had a lot of sleep, more than usual.—God bless you my dear, my love to you[.] Aline

Aline Bernstein at 333 West 77th Street, New York City, circa 1925–26 (Courtesy of Edla Cusick)

5. [New York, 3 June 1926]1

My dear:

I want to tell you that I put your money etc, in an envelope with my name upon the outside, and put the envelope in the safe at the Neighborhood playhouse. There is also an inner envelope with your name upon it. The receipt for your ticket from the Frank Tours Co. I forgot to include,2 I still have it in my purse. But it is a relief to me to have the money in a safe place for you[.] God forbid that any thing will happen, but if it should, Helen Arthur knows where the envelope is.—It seems so much longer ago than yesterday that you left, and added to the fact that it is horrid without you. I have a constant little worry about your being in a wild motor ride. You have told me such tales about the carelessness of your companion. Also you have no overcoat and it is very cold here.

We are getting on with our work, but more stuff is being written and put into the show all the time,3 and tonight it seemed as though we were never going to finish. I tried several times to write you today down there but no place was quiet. I went in to the studio a couple of times and looked at your old goloshes and Derby hat right up on the same shelf with Irene’s new hat.4 I haven’t been in at 8th St. today, but I must go soon and clean it up.—Today has been heavenly weather[,] clear and very cool. But every one tells me I go round with a glum face. This is an old pad of paper that I bought in Paris last year, and in among the leaves I found a play that I had written some time ago. I thought it was good, but I just read it again and it is awful. Parts of it are quite nice, and there are some good ideas in it[.] But I had better stick to designing and cooking. I thought I had lost this play. You would laugh at me if you ever read it, and yet [for] some reason or other I wish [you could] read it now tonight. I [have taken] my big poetry book in bed to[night] I [am] reading up so that I can [better pass the] next test. I certainly flunked the last one, what a shame too after all the work you put in on me this year. Darling, please be an angel and don’t get drunk, or if so not too drunk too often. You are attached to me some where by a string and it keeps pulling at me.—My love to you[.] Aline

This is one Helen Arthur told me today—[G]entlemen prefer blondes, but blondes [are] not so particular.

6. Baltimore, Maryland / The Emerson Hotel / Thursday [3 June 1926]

My Dear:—

I have just escaped from my wild friend,1 sending him on, despite protests, to Washington. We put up last night at Havre de Grace after lunch at Princeton and supper at Philadelphia. Town filled with Shriners and American flags. Havre de Grace pleasant. Drive over this morning beautiful. The trees of Maryland opulent—always were[.]

Arrived here, my friend hunted up old classmate at Yale, atty’ at law, who took us to his apartment, gave us cocktails, and had his nigger fix us lunch. Soup, peas, potatoes, veal cutlets, tomatoes, strawberry shortcake, coffee. Most good!2

I’m going down the bay to Norfolk on to-night’s boat. Friend wanted reason—I had none, which he couldn’t understand. Thank God, I’m alone. Back to the same of that summer’s misery and enchantment when I was seventeen.3 By Bacchus, how the rubble gleams when touched by the lights of the carnival!

I may meet the Demon Drink Saturday in Richmond—he, afraid desperately [of] being alone, but understanding it in me[.]

My dear, I have been gone a day, and I still love thee. Be thou ever—and ye will! Semper (in)fidelis!4 Tom

Wire me Saturday to the Jefferson Hotel, Richmond, Va.

7. New York / Neighborhood Playhouse [4 June 1926]

My dear,

I had your letter with my morning coffee, and I will take a chance that this may reach you at Richmond. The letter made me so happy, I have been walking on air all day. It made me happy all but the Latin Tag, with the prefix crossed out. But I know what I know, and that is how dearly I love you and how I am yours within myself. I wrote to you yesterday, to Asheville and will telegraph tomorrow. We are loading up with more and more to do. It was a relief to know you are no longer with your wild companion.—You are my wild companion, and I hope you will always be so. The way I care for you is like a cube root. It just multiplies in every direction. God bless you[.]

Aline

I am trying to write this with every one coming in to ask questions. I wish I was a better writer—

8. Norfolk, Virginia / Hotel Southland / Friday night [4 June 1926]

My Dear:—

I am sleeping, you observe, “where life is safe,”1 and have spent part of the day in a series of parleys, debates and refusals with one of the negro bell-boys, who wants to sell me a pint of corn whiskey, a quart of gin, and a girl, “who’s jest beginnin’ at it”—all reasonably priced.

I came in on the boat this morning at an ungodly hour—seven o’clock, which means six because Virginia is not on daylight savings. (Though God knows why she should be!) My song is “hollow, hollow, hollow”2 (“Did you ever yearn?”) I am the fabulous Saint, Thomas the Doubter, who at best has never doubted, and who is always fooled. Someday I shall return somewhere and find not only doors and windows bigger, but the roses blooming as I knew I left them.

Here, in this dying town, the drear abomination of desolation, I spent a summer of my youth eight years ago, gaunt from hunger, and wasted for love, and I saw the ship and the men go out, the buttons, the tinsel, and ...