![]()

1 Eros and the Origins of Art

Girodet's Mythic Meditations

Imagination is the core of desire.

–ANNE CARSON, Eros the Bittersweet

At the 1793 Salon in Paris, Anne-Louis Girodet exhibited The Sleep of Endymion (plate 4), a work that catapulted him from the status of student artist to accomplished master. As has often been noted, observers of the time marveled at the artist's ability to transform an academic requirement for the male academy nude into a tour de force in a brilliant mythological painting that enthralled the viewers of the period and set a new standard for innovation in visualizing myth. If David's Loves of Paris and Helen announced a new path for mythic representation to follow, Girodet's Endymion built upon this momentum and took it to the next level. During a period of revolutionary tumult and social and political upheaval, the success of Endymion confirmed the extraordinary hold of myth on the popular imagination. The mythological momentum that had been building in the preceding decades was not interrupted or even slowed down by the Revolution. In fact, in some ways the Revolution seems to have provided intensified energy for written and visual meditations on myth. We certainly see this in the case of Girodet.

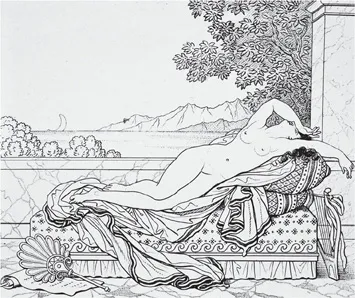

To a greater extent than most of his peers, Girodet was obsessed with myth. He was particularly fascinated with the role of eros and desire. Girodet's mythological production was vast, and he sought to enrich the iconography of myth through continual innovations, as manifested in numerous paintings as well as in a large body of drawings, studies, and oil sketches.1 A considerable number were directly related to his lifelong project of illustrating the ancient poets, whose works he translated into French himself.2 His compositions for Didot's edition of Virgil in the early 1790s launched him in this direction. While working on the Didot compositions as a student in Rome, he was likely inspired by John Flaxman, whom he befriended there. Flaxman was in the Eternal City in the early 1790s working on his innovative outline illustrations to the Iliad and the Odyssey, a project that, as is well known, would profoundly in fluence French and European artists working in the neoclassical style.3 Girodet was present during the very period of inception and creation of these images, and his many outline compositions owe a clear debt to Flaxman's stylistic innovations, as we can see in the sensuous Love Seizes Sappho (figure 20) from his late corpus, a drawing made to accompany his French translation of the Greek poetess.4 It is important to keep in mind that Girodet, to a degree that surpassed most of his fellow artists, was exceptionally literary and learned. He was an intellectual who pursued the study of many disciplines, including ancient and modern literature as well as the natural sciences.5 Girodet's vast library, which covered widely divergent disciplines from physiology and botany to aesthetics, was filled with editions of the Greek and Latin poets.6 He aspired to be a writer and translator as well as a painter, and for him painting and drawing were supremely intellectual undertakings. Girodet was close to many writers of the time—poet François Delille (who was principally inspired by Greek and Roman poets), Chateaubriand, and Bernardin de Saint Pierre, among many others. The Romantic poet Alfred de Vigny was his student.7

Figure 20. Anne-Louis Girodet. Love Seizes Sappho. Engraved by Charles Chatillon after Girodet, 1826.

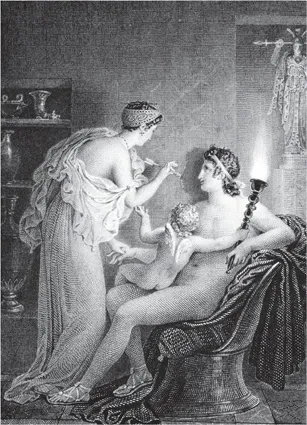

In Girodet's capacious mind, writing poetry and prose and translating ancient poetry into modern French went hand in hand with his creation of drawings to visualize the words. His profound interest in translation, which involved an examination of language and its meanings, finds a parallel with his translation of mythic narrative into visual form. His lifelong love of the ancient poets, especially Virgil, Ovid, Sappho, and Anacreon and the lyric poets Bion and Moschus, inspired many mythological compositions. Illustrations to these poets abounded in the eighteenth century, but Girodet wanted to create original compositions that diverged from these precedents. A majority of his compositions engage themes of erotic desire and sensual pleasure, as in the rapturous oil sketch (seen here in Chatillon's print) inspired by Anacreon's Ode XXIII (figure 21), which in his translation Girodet entitled “Sur l'or” (“On Gold”). The image visually translates Girodet's last lines of the ode in his own French version: “Well, as long as the sun rises for me, scorning riches, plunged into a sweet inebriation, I want to dally with my friends or hold in my arms a loving mistress, with rosy skin and lily-white breast.”8 These lines make clear the poet's preference for enjoying life and accumulating moments of pleasure to the accumulation of gold. In the composition, the older, bearded Anacreon reprises the position of Girodet's Endymion, as he enjoys the beautiful nude young woman swooning in sensual pleasure against him. An ephebe fills the poet's cup with wine, so that we know he is “plunged into a sweet inebriation,” one fueled by wine as well as sexual pleasure. The perspicacious art theorist, critic, and archaeologist Toussaint-Bernard Emeric-David wrote that the compositions revealed that the artist had so completely immersed himself in the poet's verses that he came to identify with Anacreon.9 Girodet's biography suggests his great empathy with Anacreon's celebrations of sensual pleasure and erotic love.

Figure 21. Anne-Louis Girodet. On Gold. Anacreon, Ode XXIII. Engraved by Charles Chatillon after Girodet, c. 1826.

Girodet's On Gold is a late manifestation of his meditations on myth, part of a continuum that begins in the 1790s and is related to the genre of innovative and imaginative illustrations of the classical poets, launched by his commission for Didot's edition of Virgil. One of his most captivating and complex images iconographically, which may also date from this later period, is his drawing The Judgment of Midas (figure 22), inspired by the episode in Ovid's Metamorphoses.10 In his depiction of the music contest between Pan and Apollo, judged by the king of the mountain, Timolus, Girodet makes many imaginary additions to the scene, bringing together as witnesses to the judgment mythic lovers from multiple sources, including his own paintings. Some of the figures are associated with the amatory biography of Apollo.11 Midas is witness to this triumphant moment when Apollo is about to be crowned victor—the music of his lyre is far more beautiful and refined than Pan's crude woodland pipes.

Figure 22. Anne-Louis Girodet. The Judgment of Midas. Louvre, Paris. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

Midas had renounced wealth after the unfortunate episode of his absolute greed. Bacchus (who, accompanied by his leopard, reclines behind Apollo with his beloved Ariadne in his arms) had originally granted Midas his wish that all he touched be turned to gold and then rescued him from starving to death (golden food cannot be eaten) by lifting the curse. But Midas did not learn from experience and continued to make poor decisions. He supported Pan, the woodland divinity who was half man and half goat, when this rustic god foolishly challenged Apollo, god of art, music, and civilization as well as reason. Apollo punishes Midas for his stupidity and ignorance by giving him the ears of an ass. We see Midas in the foreground in agonizing pain as he suffers this transformation, while a defeated Pan slips away with his crude pipes but glances back at the victor being crowned. Timolus's gesture of proffering the crown is echoed by a small adolescent Eros, one of Girodet's additions to the narrative, who also offers a wreath to the youthful Apollo. For Girodet, Eros must be present at the creation of art because he is its impetus and inspiration.

He makes this clear in an epic poem he wrote on the art of painting, begun in 1800 and completed in 1824.12 In the first canto, he describes how Eros is the origin of art: “Which god brings you [art] into being? Is it the blond Phoebus Apollo? No, it is a greater god, the son of Venus; this god whom the gods themselves worship for his power, from his ethereal breath art comes into being—without him, you [art] would still be in the void.” The poem continues with the story of Dibutades, the woman who created the art of drawing by tracing the outline of her lover's silhouette on a wall, as recounted in Pliny. Girodet made an exquisite drawing of Dibutades in 1820, which was engraved posthumously in 1829 (figure 23).13 He interprets an oft-represented subject in art and one understandably germane and dear to artists.14 Intensely concentrating on her drawing, Dibutades inscribes with Eros's arrow the profile of her lover on the wall, whose shadow is cast by Eros's torch. With his back to the spectator, Eros sits in the lover's lap as he gazes upon the emerging outline drawing. Dibutades holds her lover's hand while he looks ardently into her face. We see the inventor of drawing, a woman artist it should be noted, inspired by her erotic attachment to her beautiful, idealized, nude male model.

Girodet, as we can see, was fascinated by the god Eros, who received renewed attention in European painting and sculpture in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. We will explore the many manifestations of Amor/Eros more extensively in the next chapter, but we now turn to a principal direction in Girodet's visual meditations on the god of love, one that was more rarely represented during this time and that we see in several of Girodet's paintings—namely Eros as revealer.

Girodet's fascination with the god of love as revealer was directly related to his ideas of myth as revelation of the science of nature. He announces his fascination with Eros as revealer in The Sleep of Endymion (plate 4), of 1791–93, a painting that has been written about extensively in the past twenty years. Eros in this painting reveals the sleeping figure of Endymion to the goddess of the moon, Diana, who has fallen passionately in love with the sleeping shepherd. The figure of Endymion itself, with its grace, beauty, and feminine or ephebic qualities, has been the object of much fructive interpretation and has been variously interpreted as a political allegory, a homosexual invitation, a counterstatement to revolutionary masculine ideals embodied by the iconic image of Hercules, among others.15 What I would like to emphasize is the painting's innovative iconographic additions to a continuum of established prototypes of the beautiful male ephebe, as seen in famous antique examples such as the Antinous, the youthful Bacchus, or the Apollo Belvedere (figure 24), hallmarks of the neoclassical aesthetic, as well as in celebrated Renaissance and Baroque precedents, including those found in the works of Correggio, an artist Girodet, like many of his contemporaries, greatly admired and emulated.

Figure 23. Anne-Louis Girodet. Dibutades. Frontispiece to P. A. Coupin, Oeuvres posthumes de Girodet, 1829.

Girodet's Endymion seems in particular to have direct links to the figure of the famous antique ephebic Apollino (figure 25), which can be seen in various incarnations in French rococo painting, such as Nicolas Bertin's Bacchus and Ariadne of 1710–20 (plate 1). (A plaster copy of the Apollino, known previously as the Medici Apollo, had been in the French Academy in Rome after 1684.)16 In Bertin's painting, the sensual, youthful Bacchus, with sinuous curves and long, flowing, golden locks, is the beloved of the beautiful Ariadne. His pose and stance are based on the Apollino. A fascinating feature of Bertin's painting and many others like it in eighteenth-century French painting is that the “effeminized” male is the object of female desire. This tradition remains unbroken throughout the eighteenth century, transcending both stylistic transformations from rococo to neoclassicism and aesthetic doctrine and categories, as well as political regimes. The taste for ephebic male beauty, in fact, as seen in Bertin's painting from the early eighteenth century, predates by decades Winckelmann's theories of ideal beauty (the “beau idéal”) that eulogized the male ephebe in ancient art as an avatar and is often pointed to as a starting point for this direction in neoclassicism (see chapter 2).17 In Girodet's painting, we see two such male ephebes, for the figure of Eros himself, younger and more slender than Endymion, is his equal in sensual beauty.

The Sleep of Endymion (plate 4, figure 26), begun in Rome in the spring of 1791 and completed by September, was immediately recognized at its first exhibition at the Salon of 1793 as a mythological masterpiece.18 Girodet intended it as the required male academy nude to be sent back to Paris as a measure of his progress, and, as has often been noted, he transformed this required piece into one of the most innovative reinterpretations of myt...